On Oct. 16, Ramon Martinez took a plane from Mexico City to Atlanta. He had never traveled to the city before but was moving there because he had been hired to do one particular job. A job that very few can do in the South because the skill set is earned in Mexico.

Martinez is a taquero — a traditional taco maker.

When chef Santiago Gomez decided to open a taquería in Atlanta with his parents, he never imagined that his biggest challenge would be finding a traditional taquero.

“We’re demanding the respect that we deserve for really being the backbone of the restaurant industry in this country.”

“Even I can’t do that job,” said Gomez. Born and raised in Mexico City, Gomez is an award-winning chef who has opened and worked at many prestigious restaurants across Mexico and the United States. His second venture in Atlanta, El Santo Gallo, is a casual taquería bringing Mexican street food to Atlanta’s nightlife scene.

“A taco is always a craving after a night out,” said Gomez. “In the area, there are not many taquerías open late or where diners can actually see the taquero doing their thing on the trompo. It’s a whole experience, and it was important for us to have that.”

But finding a taquero that could master the vertical rotating spit of seasoned meat known as a trompo was the most challenging part of the business journey — even for an experienced restaurateur like Gomez.

After six months of searching, researching and negotiating across the South and even Mexico, Gomez put his highest-paid employee for El Santo Gallo on a plane from Mexico City.

“Ramon and I have never met in person,” said Gomez. “But he is exactly what we are looking for.”

For Martinez, coming to the United States to do what he has done for 40 years in taquerías in Mexico City could be a life-changing opportunity.

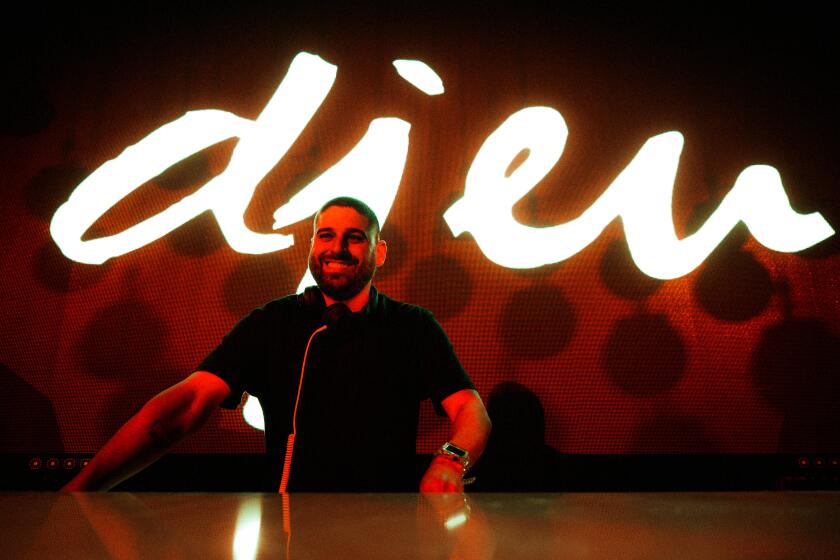

For more than 15 years, DJ EU has been consistently showing up and putting all his energy and effort toward elevating the nightlife scene in Atlanta with his Latin roots at the forefront.

“I was born in a small town near Mexico City, and by the age of 9, I was already working with my family on a farm,” said Martinez. “We moved to the city, and I started working at the taquería doing every little job before I finally got the opportunity to reach the highest role there — to be the taquero.”

In Mexico, a taquería is always just a block or two away from wherever you are. As night falls, taco stands rise, bringing light to dead corners and a second life to some businesses — such as El Vilsito, an auto shop by day and one of Mexico City’s most famous al pastor taquerías at night.

Mexicans rely on the taquería, and el taquero is the unsung hero at the end of a long day or after a night of partying.

“Going out for tacos with friends is such an intimate thing,” said Concepcion Romo, a Mexican party planner who often hires taqueros. “You don’t just go anywhere. You go where someone recommended you to or where friends took you. A taquero is almost an extension of your family.”

The job does not require a culinary or college degree, in fact, it does not even require a high school diploma. But it does require the trust of another traditional taquero to want to teach you.

Like Martinez, many taqueros start working at a very young age and have been in the industry for years. And while they may not have a fancy degree, many could beat any college grad with their memory, math and task management skills. Taqueros notice everything while they’re working, and the mind-blowing mental notetaking skills required for this craft might surprise you. You might lose count of the tacos you order and eat, but your taquero won’t.

Their quick and precise chopping skills are worthy of culinary praise. The technique of sliding the knife down the vertical spit of meat, shaving off the al pastor from the trompo to the tortilla with a machete-like blade, does not come short of the knife techniques of many Michelin-starred chefs.

Many Salvadorans are raised to believe there are no Black Salvadorans. Afro Salvadorans still face stigma, and even erasure.

“That’s how you spot a real taquero,” said Martinez. “It’s all about the precision and technique when making a taco al pastor.”

The taco al pastor is the most representative taco of Mexico City. But before it was a taco al pastor, it was a Lebanese shawarma.

In the 1930s, Lebanese immigrants escaping the Ottoman Empire arrived in Mexico through Veracruz, settled in Puebla and eventually made their way to Mexico City. Some Middle Eastern cooking techniques and dishes came with them, including the shawarma, a spit-roasted lamb served in pita bread.

Throughout generations, the shawarma evolved. Pork replaced the lamb, and corn tortillas replaced the pita bread. The vertical spit that was invented in the Middle East in the 14th century became an icon in Mexican gastronomy and is what we call el trompo today.

Taqueros traditionally use pork loin and brisket for al pastor, but some include fattier cuts, such as leg, neck or shoulder, to create juicier tacos. The taquero cuts the meat into thin, long pieces before marinating it in adobo — a sauce prepared with guajillo, ancho and pasilla chiles and spices such as garlic, oregano, cumin, pepper and bay leaves.

In an elaborate and almost intimate process, the taquero begins to layer up the meat in the trompo, giving it the upside-down cone shape resembling the Mexican toy — hence the name.

“The process takes about an hour and a half,” said Martinez. “And we end up with a 100-kilo [220-pound] trompo, which can serve up to two thousand tacos.”

The recipe for making a trompo is unique to each taquero and taquería. It is the bearer of family traditions, history and geography.

Pumpkins are known for a ghoulish grin and delicious taste. Their origins are rooted in Mexican history

There’s no symbol that screams Halloween more than the warm glow of an orange pumpkin. But as big a part of autumnal U.S. culture as they’ve become, their origins point a bit more south to Mexico.

“El taquero has a critical job beyond just cutting meat and putting it in a tortilla,” said Martinez. “El taquero is responsible for giving the right customer service, greeting the people, offering them more tacos and drinks and checking in on them.”

Taqueros are a symbol of Mexican cuisine, and despite being essential to Mexico’s gastronomy, the profession barely provides a living wage in its home country at five thousand pesos a month — an equivalent of $277.

Meanwhile, the demand for Mexican food, specifically street tacos, has increased by as much as 31% in the last four years in the United States, creating a high demand for those who know how to do the job with traditional Mexican cooking techniques.

In places like Atlanta, where Latinos make up a smaller percentage of the population compared to cities like Los Angeles, Chicago and Dallas, tacos are in high demand, but traditional taqueros are scarce.

And that is how Martinez ended up on a plane headed to new opportunities “en el norte.”

“I met Martinez through his brother, a taquero in Miami,” said Gomez. “So, without hesitation, I got him an apartment and a job and brought him to Atlanta.”

With his talents as a traditional taquero, valued 13 times higher in Atlanta than in Mexico, Martinez will help Gomez bring authentic Mexican flavors to the South.

But, most importantly, he will help develop and teach other taqueros to do the job with traditional techniques. “Vamos a levantar ese changarro” (let’s get that business up and running), said Martinez. “Let’s show Atlanta what’s good.”

Daniela Cintron is a Mexican-born bilingual journalist whose work focuses on telling the stories of underrepresented communities. She is based in Atlanta and pursuing a master’s degree at Harvard. @danicintron

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.