The package came in the mail with my name and address written in my mom’s round, curly handwriting. I knew what was inside the soft-puffed sleeve, and it immediately set off triggers in my body.

She’d been telling me for weeks how incredible it was, how easy it was to use, and about the amazing, quick results — all the praise I’ve heard her use before about an innumerable number of weight loss schemes over the years as though she’s on Big Diet’s payroll.

This time, it was one that was catching fire as the secret weapon used by celebrities and the rich to shrink themselves seemingly overnight.

The difficulty in finding a Latinx therapist is a problem. But efforts are underway to fix the issue

I opened the package and took out two months of what she had called Ozempic but turned out to be Victoza. Her dedication to passing off a knockoff as designer is unmatched.

Typically used to treat Type 2 diabetes and other conditions, Ozempic, Wegovy and other semaglutide and liraglutide medications are part of the latest wave of weight loss solutions that people, in particular women, are clamoring to get their hands on. Whether that’s through their doctor, a medispa, a pharmacy in Tijuana, a website or by any other means.

“What happens when I can’t get it anymore?” said 40-year-old Valerie Aguilera, a project manager from Chula Vista, who first heard about Ozempic on TikTok. “It’s been working so well. What’s gonna happen when there’s another shortage?”

After seeing the drug touted as “gastric bypass without the gastric bypass,” Aguilera, who in 2011 had gastric bypass in Tijuana, went on a deep dive to learn more. She then began to search everywhere for the drug.

After months, she finally began to use Ozempic in March and has since lost 45 pounds.

“In the time period where it was hard to get, and I had to go a month without it, I noticed right away my pants felt tighter,” said Aguilera, who is hoping to lose 40 more pounds. “I just went down two sizes, and I’m not going back.”

Latinx women, and other birthing individuals, who are 35 or older and going through the fertility process deeply understand the price of time and the deeper cultural pressure that comes with it.

I have come into possession of two months’ worth of one of the most sought-after medications, currently in a shortage, because my tia was accidentally given too much by her doctor. She then turned it into an ethically murky short-term side hustle.

The popularity of Ozempic continues to skyrocket, despite growing concerns over the drug’s side effects, including thyroid cancer, muscle loss, suicidal ideation, stomach paralysis and other gastrointestinal issues. It harkens back to other weight loss “solutions” from the not-so-distant past: Fen-Phen, Herbalife, Belviq, Hydroxycut, the Atkins diet, the keto diet, Weight Watchers, Noom, jaw wires and magnets, flat tummy teas, and innumerable other drugs, fad diets and products, which have all had their moment.

Each has added to the $76-billion diet industry and has received criticism for contributing to a dangerous, fatphobic diet culture. Some were recalled over concerns about severe risks to consumers’ health.

Even so, the assurance will always be that anything that promises a thinner body will find a hungry audience.

And in Latinx communities, that feels especially true.

Efrain Pedroza, a 29-year-old who works in tech and lives in Escondido, recalled his mom eating lighter meals, going to Zumba and overall taking care of herself. But his house was always full of sodas and junk food, and he and the rest of his family were given the same heavy meals.

“I was constantly being told, ‘Don’t eat that.’ But at the same time, I was never stopped from doing it. It was always readily provided,” he said. “It was always like, ‘Why don’t you have better self-control?’ And it’s like, wait, you literally just gave me a whole other plate of food.”

The East Los Angeles author chronicles the 14-year journey it took her to complete her novel ‘Huizache Women.’

Pedroza started taking a generic version of Ozempic in April after his doctor diagnosed him with high cholesterol and high blood pressure. But he realized there were deeper struggles that pushed him into taking it.

“I think I’m lying to myself a little bit,” Pedroza adds. “That I was happy to be on this medication. It was a decision that I made to take control of being overweight but really my decision was more of this internal feeling. ‘You’re too fat. This makes you ugly. This makes you unattractive. This makes you stand out in a bad way.’”

Whether it’s our penchant for pura carrilla, an obsession with cuerpazos that deem you more desirable, or the prevalence of obesity and binge eating in Latinx communities in the U.S., the collective focus on the body and appearance within our culture feels constant and relentless.

The “pero la dieta” memes speak volumes because it does seem like we’ve all experienced bingeing followed by crash dieting, often prompted by or done alongside our loved ones. Teasing or making negative comments about weight and bodies is common in Latinx families and communities, and studies show that it directly affects a person’s well-being, leading to drastic weight control measures, low self-esteem, depression and self-harm.

But if you say that it hurts, you’re often met with a “eyyyy, no te agüites” or some other version of that.

Elena (who asked to be anonymous) is a 29-year-old writer in New York who is in her first long-term relationship. Raised in Puerto Rico, she was surrounded by pageant culture, and along with most girls in her class, she went to modeling school from an early age.

As a result, fat shaming and eating disorders were common, and she struggled with disordered eating since age 11. “Growing up, I just thought: I’m fat. I can’t be happy,” she said.

Because she’s planning to go home for the holidays, Elena has been hunting down Ozempic for months, hoping to lose weight before seeing her family. She’s currently waiting for her local pharmacy to get more of the medication.

The barrios of La Indepe used to be the margins of the industrial city, but now they are encircled by urban development. Given the government’s initiatives, often presented as progress, these barrios are the last obstacle standing in the government’s way.

When Elena got into her relationship, her mom warned her to be careful of gaining weight. “I should be celebrating that I have found the love of my life,” Elena said. “But instead I’m having my mom’s words looming over me.”

Elena believes getting on Ozempic as soon as possible will help avoid any fights with her family.

“Usually the minute I step foot in my house, what determines whether things will go smoothly or not is if my dad says I’m fatter,” she said. “One time I had lost some weight and my dad was like, ‘Oh good, you don’t look like a pan doblado anymore.’”

Growing up in Tijuana, a hub of medical tourism, I was surrounded by billboards advertising liposuction, tummy tucks and other cosmetic surgeries.

A large portion of the women in my family have had plastic surgery, and every gathering includes some mention of a procedure that would finally fix a displeasing body part.

When I gained some weight in my twenties, my sister pulled me aside to tell me I was getting fat, in a tone that indicated it was the worst possible thing that could happen. My mom also decided to “help” by offering to help pay for liposuction. When I told her she could pay off my student loans instead, she said if I got lipo, I’d find a man to pay those off.

Brutal stuff.

It was wholly unsurprising when my mom FaceTimed me buzzing with excitement over this new injection that makes you skinny, and how I should get on it. That she got it herself by sketchy means and had seemingly zero concerns about how it could hurt her or me didn’t matter.

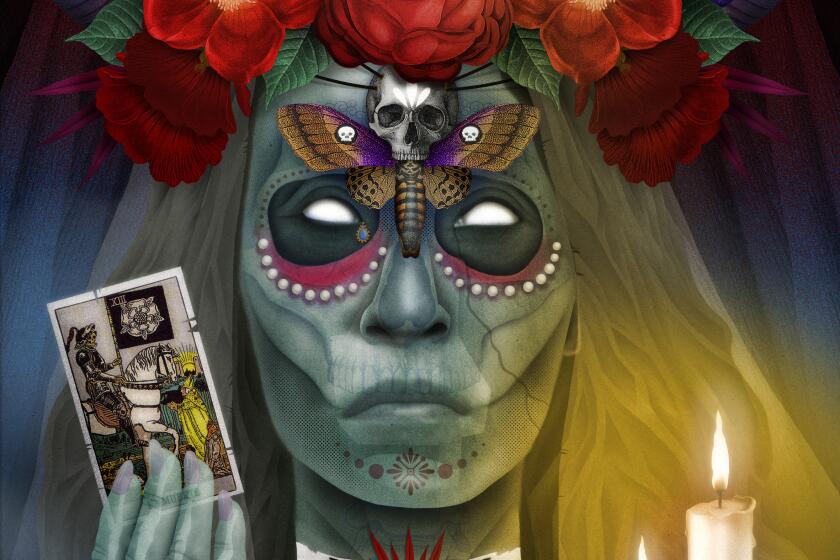

Whether La Llorona is held up as a form of resistance against oppression, owning her power or reclaiming the monstrous bruja within, the narratives of the wailing woman have endured for centuries, reimagined into a radical icon.

“In our family, with all our experimental diets and being Mexican, when something like [Ozempic] comes out, it makes it not scary for us,” said Aguilera, who started trying to lose weight at age 11. “Me and my mom have gone together to get our tongues stapled. I’ve injected so many shots into my stomach, I can’t even tell you what they were. We were never afraid of trying something new.”

Even so, Aguilera said her mom is worried about her since she has a serious blood disorder. “My mom cared about me being skinny but now because of all the blood disorder history, she’s very much more about me being alive for my kids.”

Pedroza also has to contend not just with the internal triggers around his weight and being on Ozempic but also with the physical. He stopped taking Ozempic in early October after his body began to reject food. The smell inside a restaurant causes him extreme nausea, and he now struggles to swallow anything he tries to eat. He’s worried the drug gave him stomach paralysis. “It’s scaring me because I know that I need to eat,” he said.

I’m happy the drug is there for the people who need it to live, who’ve struggled with serious medical issues tied to their weight or not and now have a powerful tool to help them heal. I just also know what drugs like this do to so many of us who have been taught to hate their bodies.

A few years ago, my niece sent me a video she found of me in high school right before a school dance. I was twirling, smiling and posing like Cindy Crawford, and then my mom’s voice can be heard saying: “Te vez gorda.”

The smile dropped from my face and I pulled my sparkly shawl over myself to cover my body. Watching that made me cry for the teenage version of me, who at that point couldn’t do what I do now, which is tell my mom: “Y que?” and then drop a hot girl pose to win the IDC war.

The injections she sent me are in a bathroom drawer, and here and there I think about them. I think about what I’d look like 10 pounds lighter. The voice never goes away, and nourishing yourself, in body and spirit, is lifelong work, especially when you’re working from a disadvantage.

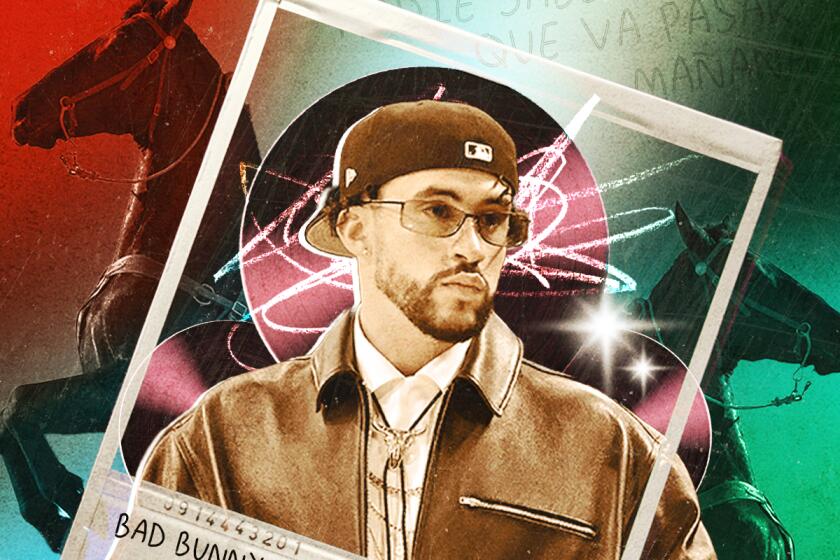

Ears-deep in his Hollywood era, Bad Bunny pulls back the curtain and lets us into his head in “Nadie Sabe Lo Que Va a Pasar Mañana.”

We fight to break these cycles and every time a new weight loss “miracle” comes around, it brings on a new round in the battle of self-love. At the very least, it’s heartening to see younger people better equipped to handle it.

“I see my nieces, they’re in their twenties and teens, and they’re bigger girls, and they are so proud,” said Aguilera. “They wear what they want. They show their stomachs. They’re always talking about how their body is ‘giving.’ I could never have that confidence that they have and I really feel it’s because we grew up the way we did. We learned not to treat our children that way. I’m happy for my nieces, and for my daughter that’s gonna grow up with all this confidence.”

Alex Zaragoza is a television writer and journalist covering culture and identity. Her work has appeared in Vice, NPR, O Magazine and Rolling Stone. She’s written on the series “Primo” and “Lopez v. Lopez.” She writes weekly for De Los.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.