If there’s one thing I’m going to do, it’s talk about people talking about food. This week, I’m venturing into even choppier waters to dive into #slopgate, an unfortunate trending topic on X, formerly known as Twitter, that started when a French user described Mexican food as “slop on a tortilla.”

This sparked heated conversation online about the quality of various national culinary traditions, a seemingly silly topic that, if looked at a bit closer, has a lot to say about why people get so precious about their culture’s cuisine.

I could come in here and white-knight for Mexican food, but I don’t believe Mexican food needs defending. It speaks for itself. Mexican food is delicious. It is recognized around the world for its rich history, its eclectic ingredients and its inventive techniques.

I’m more interested in digging into why food, specifically, reliably engenders such passionate discourse in public forums. On this front, #slopgate is a useful case study. Shortly after the original post went viral, the conversation became a toxic wasteland of people venting ethnic resentments and hitting below the belt.

“We’re demanding the respect that we deserve for really being the backbone of the restaurant industry in this country.”

But the more I thought about it, and after pushing through some truly horrendous opinions, some of which were flatly racist, I found at least one aspect of the whole ordeal quite touching. It reminded me that a culture’s cuisine is a tender, vulnerable thing. In some ways, it’s an open love letter to a way of life that is crucially available for an international audience to enjoy.

Language, holidays, death rites, these are beautiful things, and there are many aspects about them that can be shared. But there are walls in place that make them a bit more “our business.” Language, for those who weren’t born into it, can take many years to learn. Holidays, the way we celebrate births, the way we mourn our deaths — these are more intimate, family affairs. Guests are welcome, no doubt, but no cultural institution is quite as pervasive and accessible as food.

Cuisine, for a country, is really “putting yourself out there.” Unlike other cultural institutions, which have at least a few protective veils between them and outsiders, just about anyone can track down a highly recommended restaurant and get a taste of what a faraway land is all about.

Yes, some countries have more ambassadors than others. For example, I think of the wealth of delicious Thai, Indian and, of course, Mexican restaurants around the world, all countries that rightfully take pride in their culinary arts, and who take their reputation on that front very seriously.

Most cultures also put a lot of stock in making sure the house is in order before inviting guests over. At least in my experience, you want to put your best foot forward, and anyone from a Chicano household will likely understand how the opinions of absolute strangers can hold more weight than those of your blood relatives.

Recently, the Yakima Valley has received some attention because of the impressive rise of local band Yahritza y su Esencia.

To dismiss a culture’s cuisine, to deem it inferior, is like walking into someone’s house and tipping over a funerary urn.

It’s aiming right for the heart!

To bring it back to the French for a second, you know what movie really understood this? “Ratatouille.” In the scene where the food critic eats the titular dish, he is transported to his childhood, to his mother’s kitchen. Food conjures the ancestors. A family recipe is a manifesto, one that can tell a story long after the person who wrote it down has left this Earth, and anyone, absolutely anyone (without dietary restrictions, of course) can have a taste.

It’s no wonder people get anxious and emotional.

This is also why, when people claim to not like a certain cuisine, people are quick to retort, “Well, you haven’t tried the real thing.” As a descendant of Tejanos, I’ve been in the trenches defending Tex-Mex as a legitimate culinary tradition for years.

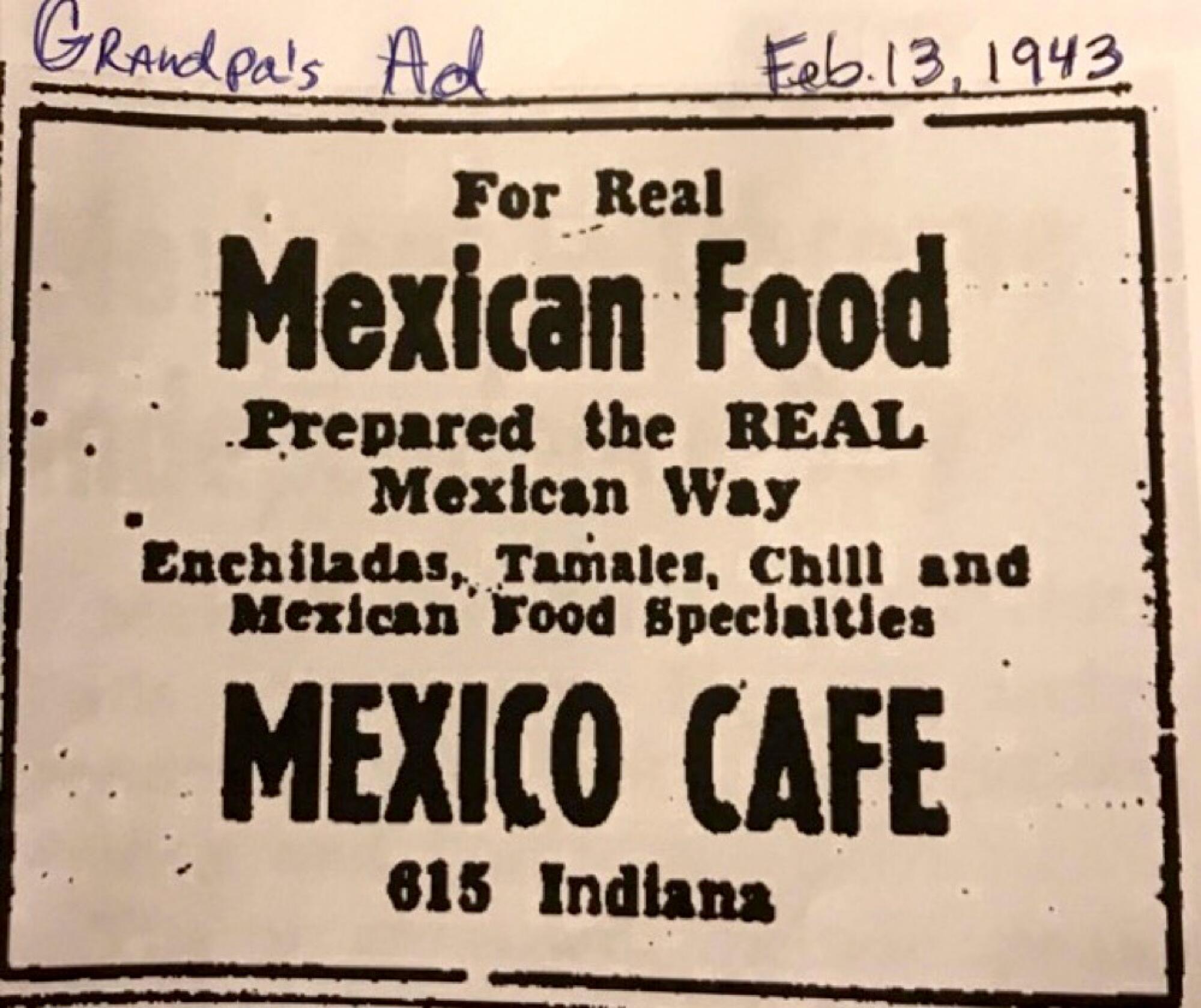

Indeed, when deriding Mexican food as “slop,” it’s likely its detractors are thinking of Tex-Mex. On that level, they might actually find common ground with Mexicans who sneer at the mere existence of Tex-Mex, who see it as an attempted deception of some kind, like it’s trying to pass itself off as “real Mexican food,” thus besmirching the mother country’s good name.

The Virgen de Guadalupe is a symbol of Mexican resistance but also one of colonization and the Catholic Church.

Not helping the case is my great-grandfather’s ad for his Mexican restaurant in Texas.

My point is cuisine is a matter of international “showing face.” People get emotional about it because, consciously or not, they see it as extensions of themselves, of the place they grew up, of their families’ kitchens. I think there’s something really endearing about that.

Sure, it results in a lot of yelling and arguing, but it’s because people care, and it speaks to the power of food as a medium for storytelling. It invites a broad array of people from different walks of life to partake. It is both intimate and exposed. For all the fuss, that’s a beautiful thing.

Of course, in the case of #slopgate, it’s impossible to divorce it from the impact of colonization and from long-standing tropes about the global south, that such places are less sophisticated, less healthy and less worthy of being deemed fine dining.

But it’s also the case that British food is a common punching bag on social media, with “beans on toast” bearing the brunt of the bullying. Many of the most vile posts about Mexican food seem retaliatory in nature, coming from Europeans who are fed up with being told their food is unseasoned gruel.

While I can’t condone the nastiness, I get it. Feelings have been hurt. But as for me, I’m no longer interested in ranking national cuisines. Sure, there are some I like better than others, but I also believe that every wonderful meal is a private universe unto itself, offering its own unique delights and pleasures. The flavors and the ambiance all conspire to create something that can’t really be compared to anything else.

This comic celebrates the importance of cultural comfort and the role that local grocery stores can play in creating a sense of home away from home.

These perfect experiences have arrived to me in the form of many different kinds of national dishes, in many different restaurants and in many different cities around the world. I don’t see why I should have to choose among them.

Or maybe I’m just hungry.

John Paul Brammer is a columnist, author, illustrator and content creator based in Brooklyn, N.Y. He is the author of ”Hola Papi: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons” based on his successful advice column. He has written for outlets including the Guardian, NBC News and the Washington Post. He writes a weekly essay for De Los.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.