Latinx Files: 50 years after their historic LACMA show, Los Four are as relevant as ever

Periodically, the Latinx Files will feature a guest writer. This week, we’ve asked Sarah Quiñones Wolfson to fill in. She is a Los Angeles-based journalist with experience crafting stories focusing on the intersection of arts, culture and social justice. She has written for outlets including the Los Angeles Times, Hyperallergic and KCET.

In February 1974, a collective known as Los Four made history as the first Chicano artists to exhibit at a major art institution in the United States. The exhibition, organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, featured works that exposed Chicano art to a broader public audience and influenced the wider art community.

For the record:

1:11 p.m. Sept. 18, 2024This edition of Latinx Files incorrectly reported that the painter and sculptor Gilbert “Magú” Luján died in 2017 of pancreatic cancer. Luján died in 2011 of prostate cancer.

Los Four consisted of Frank Romero, Carlos Almaraz, Gilbert “Magú” Luján and Roberto “Beto” de la Rocha — Judithe Hernández would join the group shortly after the LACMA show. The group members became significant figures in the Chicano arts movement. They were part of the burgeoning muralism scene and experimented with different ideologies around public-facing art, collectivism and identity, which emerged as a distinct visual vernacular and aesthetic of Chicanismo.

You’re reading Latinx Files

Fidel Martinez delves into the latest stories that capture the multitudes within the American Latinx community.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Half a century later, the impact and legacy of Los Four and their historic LACMA exhibit are being commemorated at a show at Chinatown’s Eastern Projects Gallery, which runs until Saturday. “50th anniversary of the LACMA exhibit 1974-2024” features original and new works by the founding members, providing a unique opportunity to see their artistic evolution over the last five decades.

“They’re still the vanguards of that Chicano era,” Cástulo de la Rocha, a longtime collector of Chicano art and founder of AltaMed Health Center, told me at the show’s opening back in June. “There are many young people who are here today taking notes and painting their own interpretation of what Los Four raised several decades ago.”

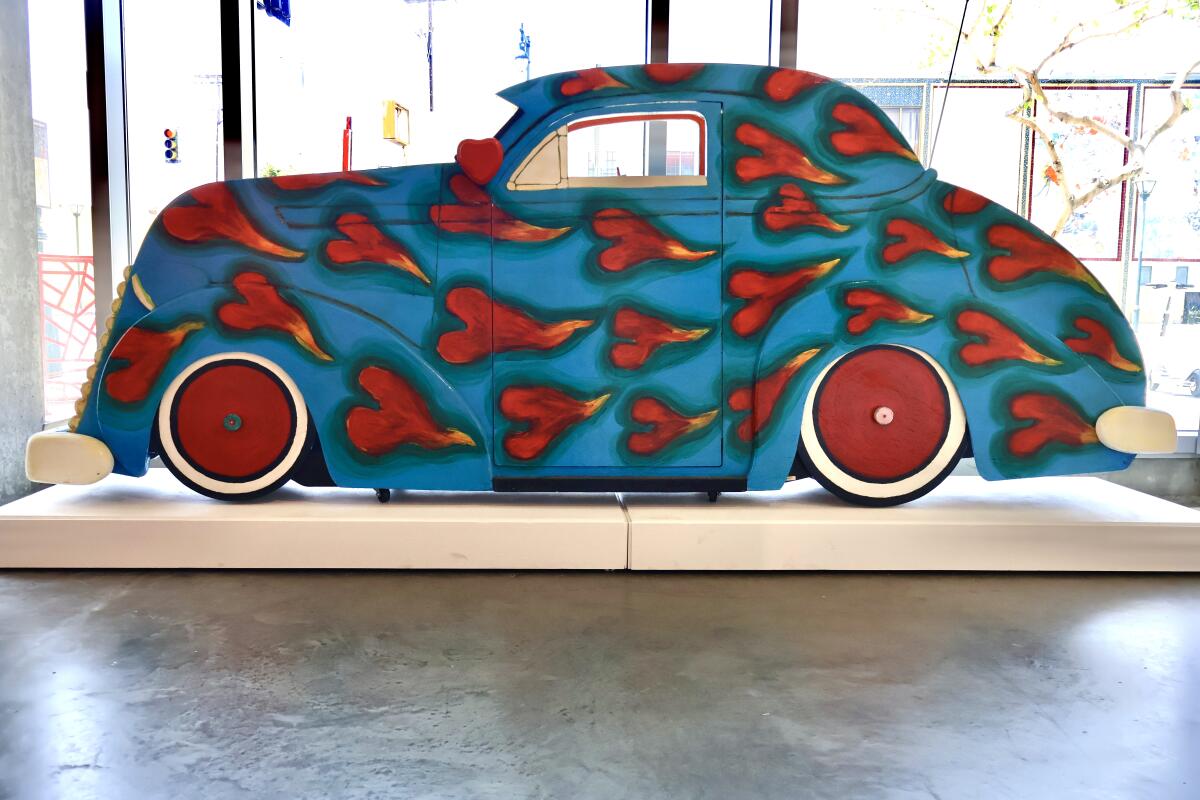

The anniversary exhibit featured poster designs advocating for farmworkers’ rights and impressionist-style landscapes where Almaraz examined political realities. Additional pieces explore his sexual identity, which Almaraz grappled with in his art practice. Romero, 83, dabbles in figurative drawings of the human form, using cultural objects like nopales or automobiles to make social commentary. Luján, a painter and sculptor, was known for incorporating pre-Columbian imagery and tapping into mythical settings that embraced Aztlan, symbolic to the Chicano movement. De la Rocha, 87, highlighted his graphic design skills in a maze-like still-life drawing, “La Mesa de Frank,” that portrayed a tablescape in the home once shared by Romero and Almaraz, which became a hub of roundtable discussions and debates for the group.

The origins of Los Four officially began in 1973, but the artists would meet organically at different points in their lives. Romero and Almaraz met while attending California State College (now Cal State L.A.). Almaraz was first introduced to Luján because he was the director of art journal Con Safos. De la Rocha was brought into the fold by Luján, who often recruited Chicano artists for projects.

As part of Luján’s MFA thesis, he set up a group show at UC Irvine with curator and educator Hal Glicksman that focused on Chicano art. “We decided to do a bicultural, bilingual show,” Romero said. This decision marked the formation of Los Four.

In their work, the artists integrated symbols, iconography and ideas that spoke directly to the Chicano community. It embodied the concept of “rasquachismo,” a working-class, DIY aesthetic that often employed found objects — they did the most with the least.

The two-month show was such a success it caught the attention of LACMA curator Jane Livingston, who offered them an opportunity to present an extension of their exhibition, “Los Four: Almaraz/de la Rocha/Lujan/Romero.”

“The truth is they gave us a teeny space and two rooms,” Romero said with a smile. “Four artists descended at LACMA, filled with a huge pickup truck. We kept bringing things in — Gilbert wanted to put an entire car in there, but it wouldn’t fit in the elevator. So we had to put in half a car and kept making demands. All of a sudden, they gave us the entire Anderson wing of LACMA.”

On opening night, attendees stood shoulder to shoulder.

“We heard we broke all attendance records,” Romero said. “There was a trail around the block.”

After the LACMA show, Los Four toured college and university museums. But the group dynamic began to shift— Luján temporarily left due to a reported disagreement over exhibiting at the Oakland Museum. De la Rocha would quit art altogether for 20 years.

“With the museum thing, I expected the whole world to open up to me,” he told the Times in a 1995 story about his return to making art. “[But] nothing happened. I didn’t know how to wait for success, how to be patient. I had this idea back then that once you began to work as an artist you could buy your car and have food to eat and raise your family. That doesn’t happen. Very few people make any money at this profession.”

Los Four quickly evolved, collaborating with various artists on mural projects. Activist and artist Hernández soon joined the collective, offering a feminist perspective that challenged the status quo. They also found solidarity among other groups like East L.A.’s Asco and muralists East Los Streetscapers. They were active with the arts advocacy organization Concilio de Arte Popular, a network of Chicano collectives from various art disciplines that published a magazine called Chisme Arte. This camaraderie spoke to what they, as a whole, were achieving in the arts canon.

In 1983, Los Four disbanded as members of the collective and pursued personal endeavors, moving toward studio work and pushing Chicano art into public consciousness.

“Many artists followed [Almaraz] and started showing in mainstream galleries. Prior to that, we were barrio-ized — they didn’t consider Chicano art part of fine art in this country,” said Elsa Flores Almaraz, widow of Almaraz and an artist in her own right.

In recent years, several members of Los Four have been recognized by museums with retrospectives of their work and displayed at galleries worldwide.

The celebration at Eastern Projects was a reunion of old friends, relatives and members of creative circles spanning across demographics, chronicling the days of the past and reminiscing and honoring those who have passed away — Almaraz died of AIDS in 1989 at 48, and Luján from pancreatic cancer in 2017 at 70. Attendees were there to pay tribute to Los Four’s creative and historical roots.

“Fifty years later, this show is as important today as it was in 1974,” said Rigo Jimenez, founder of the Eastern Projects Gallery. “These four individuals formed a collective to tell the stories of our communities through their art and bring about social change. This show honors the legacy of these four Chicano artists, who planted the seeds for generations of artists to come.”

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Stories we read this week that we think you should read

Column: Can Antonio Villaraigosa charm his way into becoming California governor?

Antonio Villaraigosa is once again running for governor of California. In his latest, columnist Gustavo Arellano speaks to the former Los Angeles mayor about his upcoming campaign.

Los Ángeles Azules to be honored with Hispanic Heritage Award

The Mexican band known for its signature cumbias is scheduled to perform at the Kennedy Center celebration airing Sept. 27 on PBS.

Isaac Psalm Escoto finds the intersection between L.A.’s art galleries and graffiti

Under the moniker of Sickid, Escoto has spent years sharing his art on billboards and buildings. “Gas Station Dinner,” his first major solo show, brings these characters to the Jeffrey Deitch gallery.

Laurie Hernandez’s NBC commentary sticks the landing at Paris Olympics

The 24-year-old decorated gymnast shined as a commentator for NBC, delivering viral moments in the spirit and joy of the Paris Olympics.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.