Gascón gave teen killer second chance — now she’s charged again

The crime Shanice Amanda Dyer committed as a 17-year-old was as horrific as it was seemingly random.

She was a documented member of a Crips street gang faction in South L.A., according to appellate records from the case, and she wanted to help retaliate for killings by a rival group in August 2019.

The targets the gang chose at random were an expectant father, Alfredo Carrera, and his close friend Jose Antonio Flores Vasquez, an aspiring astrophysicist in UC Irvine’s doctorate program who was visiting Carrera to drop off a baby gift. A car pulled up, with Dyer inside. After a brief argument, authorities said, Dyer and two other defendants unleashed a volley of gunfire, killing both men. A third man down the street was wounded in the back as he loaded his 1-year-old daughter into a car seat.

Dyer sent text messages taking responsibility for the shooting, saying she was “satisfied” it made headlines, according to a court of appeals filing that documented evidence gathered from her Instagram account.

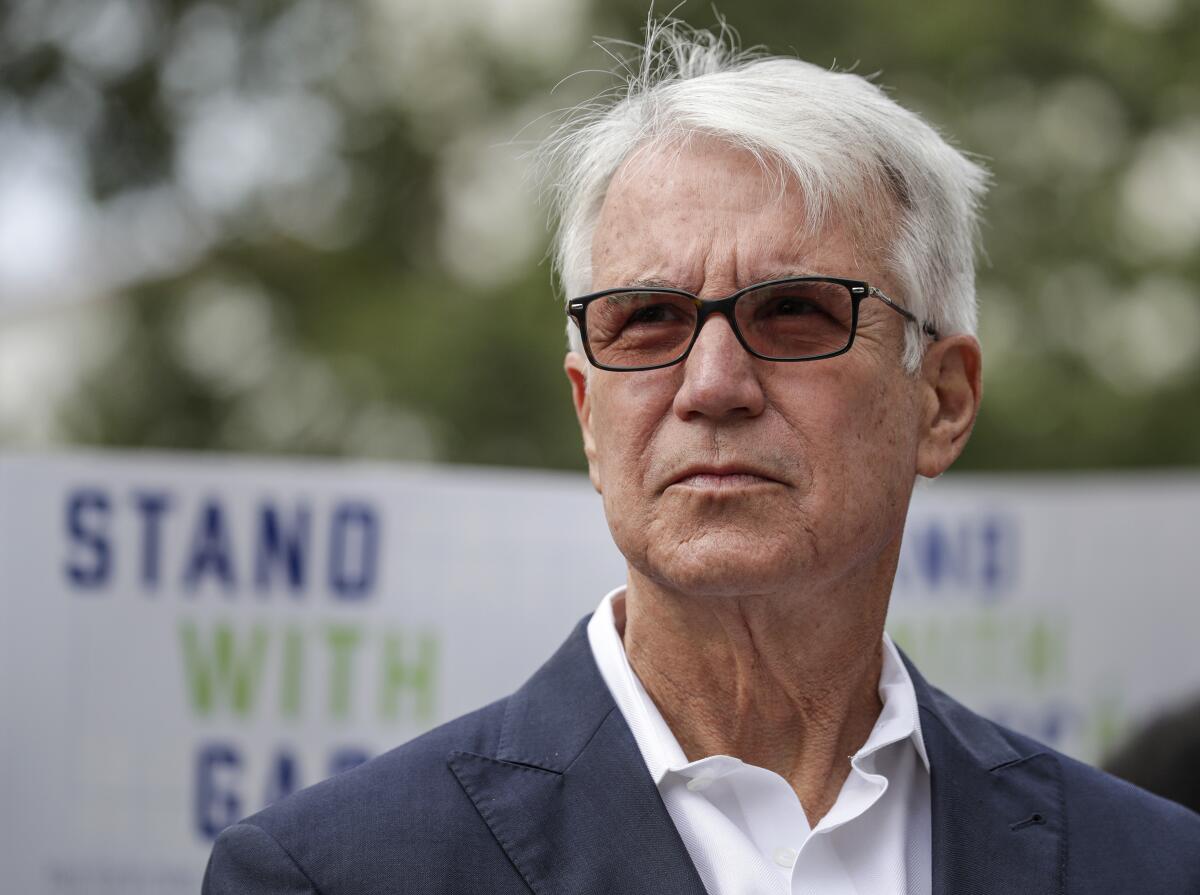

Dyer was tried as a juvenile under Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón, who at the time had a strict policy against prosecuting teens as adults. She admitted to the murder charges in 2021, and probation records reviewed by The Times show she was released last February. Six months later, she was arrested in connection with another homicide, this one in Pomona.

Dyer’s case is one of several in which a defendant to whom Gascón showed leniency has been released only to be accused of another violent crime. Now, with the incumbent district attorney taking heat for progressive policies from his challenger in November’s election, the question of how to handle the most violent of juvenile offenders has become a key issue.

After L.A. County prosecutors decided not to try him as an adult in a 2018 murder, Denmonne Lee responded well to programs in juvenile halls. He started attending community college and found a job. But now he’s been arrested in a second killing.

Although Gascón’s juvenile policy is in line with a broader movement to keep youths out of adult prisons in California — where only a dozen teens were tried in adult court last year — Dyer could have faced life in prison for the double murder if her case had not stayed before a juvenile court judge.

In the recent case, prosecutors allege that in June she lured Joshua Streeter, 21, to a Pomona strip mall where he was shot dead. Although not accused of pulling the trigger, Dyer, now 22, is again charged with murder.

Court records show she has not entered a plea and is due back in court next month. Her attorney declined to comment.

When Gascón took office in 2020, he barred prosecutors from charging juveniles as adults under any circumstances, citing research on adolescent brain development that shows people do not fully mature until age 25.

Gascón backpedaled on his ban halfway through his term, deciding to allow prosecutors to seek transfers to adult court in some instances. The move came after widespread backlash over the case of Hannah Tubbs, a 26-year-old who was tried in juvenile court for a sexual assault she committed as a teen.

Charging juveniles as adults requires judicial approval, and the bar tends to be high. Two-thirds of attempts to transfer teens to adult court failed last year, according to a report published by the California attorney general’s office.

Attorney Nathan Hochman has “broad-based support” across many groups of potential L.A. County voters in his race against Dist. Atty. George Gascón, according to a new UC Berkeley poll cosponsored by The Times.

But critics of the “godfather of progressive prosecutors” maintain that harsher punishments for violent teenage offenders should be pursued more aggressively.

Shawn Randolph — the district attorney’s former top juvenile prosecutor, who alleged she faced retaliation after pushing back against Gascón’s policies and won a lawsuit against him last year — called the latest alleged killing by Dyer “predictable and preventable.”

On Gascón’s initial ban on pursuing adult charges, Randolph said: “He ordered that juveniles that had demonstrated a propensity to kill would be released well before their brains had finished developing, unleashing them on a vulnerable public to kill again.”

Under Gascón’s current policy, L.A. County prosecutors seeking to charge juveniles as adults have been required to send cases to an internal committee; 23 such proposals have been approved, according to the district attorney’s office, and only one has been transferred into adult court by a judge.

Tiffiny Blacknell, Gascón’s chief spokeswoman, said it was unlikely Dyer’s initial case would have met the standard for a transfer to adult court even if Gascón had allowed pursuing that option in 2021. Blacknell said the teen had no criminal history, and “evidence indicates that she was told to commit the crime by someone of greater influence due to age and status in the gang,” which is a factor when determining whether a minor can be transferred to the adult system.

Blacknell said another teen suspect involved in the killings was also tried as a juvenile and “is now doing well on probation.” An adult suspect in the those killings is still awaiting trial, according to Blacknell.

The candidates for Los Angeles County district attorney will square off weeks before November’s election in an event co-hosted by KNX and The Times.

Winning a motion to transfer a teen to adult court in California has become increasingly difficult, in part because of a 2022 Assembly bill that Gascón supported. The legislation requires prosecutors to prove “by clear and convincing evidence” that a youth can’t be rehabilitated in juvenile custody before a judge can approve a transfer.

Some prosecutors argue the new standard borders on the impossible. In 2022, an Inglewood judge decided a teen who was accused of gunning down his girlfriend and her sister in Westchester before setting the crime scene on fire still did not meet the standard for transfer to adult court.

Former federal prosecutor Nathan Hochman, running to unseat Gascón, said his opponent “could not have handled the Dyer case any worse.”

“First of all, he imposed a blanket policy refusing to transfer any juveniles to criminal court under any circumstances. He also rejected the recommendation of his senior prosecutors who warned him that if she were kept in juvenile custody and released in a few years, she very likely would kill again,” Hochman said in a statement. “What I will do is empower my prosecutors to make the best decisions based on two things: the facts and the law.”

Asked what strategies he would use, if elected, to try to overcome the high burden of the state law on transfers, Hochman said he would “never shy away from a difficult fight,” but did not offer specifics.

Changes in state law governing juveniles have mattered little to crime victims who draw a straight line between Gascón’s actions and street violence.

Alfredo Carrera’s sister, Cynthia, said her family was not notified of Dyer’s release this year.

“She’s a cold-blooded killer set free,” Cynthia said of Dyer. “It is pretty shocking she was able to do it again. That is what comes from the soft-on-crime laws in L.A.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.