UC Berkeley’s new chancellor plans to ‘question the status quo’ as he takes over

UC Berkeley may be best known as the birthplace of the student free speech movement and for its ranking as one of the world’s top public research universities.

But as incoming Chancellor Rich Lyons kicked off the new school year last week, he leaned into a less well-known standing: It is the world’s No. 1 university when it comes to producing venture-funded start-ups founded by undergraduate alumni.

Before 9,000 new students at their welcome ceremony Thursday at Haas Pavilion, Lyons highlighted that “grand scale” of campus innovation and entrepreneurship and “the Berkeley way” of questioning the status quo to generate new ideas.

In an interview, Lyons focused on that theme, saying new ideas are needed to help tackle Berkeley’s toughest problem: bringing financial strength to a campus struggling under state funding deferrals and an ongoing structural budget deficit. In the last eight years, Berkeley has wrestled with two budget deficits and faces another one of up to $150 million in 2024-25 due in part to rising expenses, such as mandated pay increases. The campus has not yet decided whether to further dip into its reserves.

But the campus can potentially generate an eye-popping $1 billion in new revenues over the next 10 years though entrepreneurial ventures, said Lyons, who previously headed the Haas School of Business. A professor of economics and finance, Lyons also served as associate vice chancellor and chief innovation and entrepreneurship officer before taking over in July.

“It needs to be something fresh. It needs to be something new,” said Lyons, clad in jeans and a “Berkeley Changemaker” top as he laid out his ideas. “It needs to be large enough ... to be transformative.”

Protests: ‘We plan to be firm’

Lyons, 63, also addressed protests, which are expected to ramp up this week as students returned to campus. Last spring, pro-Palestinian supporters drew global attention when they set up tent encampments at Berkeley and elsewhere. Some were peaceful gathering spots for solidarity activities — Berkeley managed to reach agreement with protesters to end their encampment voluntarily. Others became conflict zones with counterprotesters and were forcibly dismantled by law enforcement.

Pro-Palestinian protesters at UC Berkeley removed their encampment after talks with the university, which said it will consider their divestment demands.

Protest activities this fall will draw new scrutiny after the University of California and California State University directed all of their campuses to take a zero-tolerance approach to those who violate rules against encampments, blocking access to buildings and walkways and masking to conceal identity while committing wrongdoing. The directive was driven by state lawmakers who told UC and CSU to develop a “systemwide framework” to provide consistent enforcement of rules — and are withholding $25 million in state funding from UC until President Michael V. Drake delivers a report on his efforts by Oct. 1. No state funding is directly involved for CSU.

Lyons said he would honor free speech rights but enforce rules about how and when to exercise them.

“There are hundreds of places on the Berkeley campus for students to express their free speech rights,” he said. “It’s part of our culture. We are a free speech university. But to intentionally break the rules ... now you’re in the world of civil disobedience and we’re going to think about consequences.”

He said the key issue of when to escalate action against those who break campus codes under UC’s “tiered response” framework will depend on the situation — whether they are students or outsiders, whether they are repeat offenders, whether the action is intimidating and jeopardizes the rights of all students to feel welcome and safe.

“There is no obvious answer here,” he said. “As the chancellor, timing is my call. We plan to be consistent and we plan to be firm and we plan to abide by the directive.”

Regarding the ban on masking, which has drawn widespread questions, Lyons clarified that Berkeley would not challenge face coverings unless worn by someone who was violating rules or laws. The campus’ written policy states, “People are permitted to mask, and campus staff will not ask them why they are masked, as long as they are not violating law or policy while wearing the mask.” It also specifies that “people are not prohibited from wearing masks for the purpose of avoiding being doxxed, but they need to comply with policy and law while masked.”

Keeping neutral on social, political issues

Lyons said he would move Berkeley toward “institutional neutrality,” a policy that holds that colleges and universities should not generally take positions on social and political issues, but should instead encourage students and faculty to debate them. The University of Chicago adopted the policy in 1967. Other universities have followed after the Oct. 7 Hamas attack on southern Israel and Israel’s military retaliation in Gaza fueled pressure for statements condemning one side or the other.

USC, the University of Texas system and Johns Hopkins University also announced this month they would refrain from speaking out on social and political issues unless they were directly pertinent to their institutional missions and operations. Purdue, Stanford, Syracuse and Harvard took similar stances earlier this year.

“There are going to be fewer pronouncements about an institutional position for Berkeley, but we’re not going to zero,” Lyons said.

To help ease the searing divisions over Israeli-Palestinian issues, Lyons said several organizations across campus are working to foster dialogue. Initiatives include training on media literacy, empathetic listening, healing collective trauma and a potential new course on “openness to opposing views.”

Pressing needs

On other matters, Lyons noted that Berkeley has increased the enrollment of California students by 25% in the last decade and said funding was needed to continue growth and maintain excellence. Philanthropy can help, he said, noting a $12-million contribution from entrepreneur Scott Galloway to Berkeley and UCLA to support students who are not aiming for a four-year degree but want training in specific fields. Berkeley is using its share to fund scholarships for adults to explore introductory courses in data analytics, facilities management or project management.

Other pressing needs — supporting humanities research, doctoral students, campus libraries — require new ways to finance, he said. Berkeley estimates that potential state funding reductions could amount to $14 million less during the 2024-25 fiscal year than the campus anticipated under the original compact forged by the university with Gov. Gavin Newsom and possibly climb even higher next year.

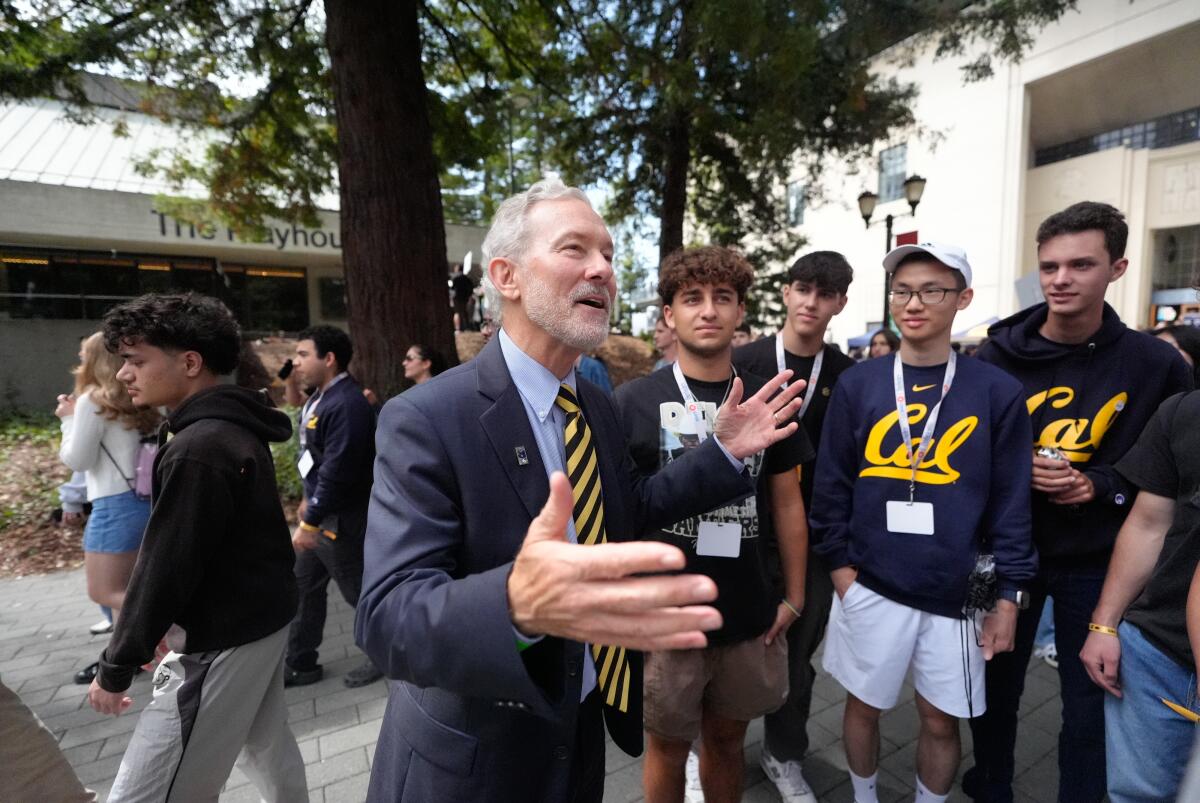

Enter innovation and entrepreneurship, the subject that most lights up Lyons. In rapid-fire recounting of different ways to raise funds, punctuated by plenty of arm-waving, the chancellor laid out various ventures he said could be financial game changers for Berkeley.

He said the campus is negotiating to receive equity positions in startups, often with a lower royalty rate, for licensing its intellectual property and now holds such stock in more than 100 companies. Philanthropists have given the campus about $75 million over the last year to invest in venture capital funds that invest mostly in Berkeley companies involved in biotech and other fields. The campus has been gifted 10% of the returns on six different venture capital portfolios. Berkeley also built a company — Second Lab — that rents out unused scientific equipment, recruiting founders from its alumni to spin it out, and negotiated to retain 16% of the firm’s shares.

“People could look at this and say, ‘That is just crazy marketplace stuff,’ but then you see we have a billion dollars that we’ve acquired in a values-consistent way,” Lyons said. “We’re finding fresh ways to deliver into that.”

UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ is stepping down after seven years at the helm, offering provocative thoughts on enrollment growth, protests and other hot-button issues.

Lyons’ energy and vision have stirred excitement. While his predecessor, Carol Christ, was deeply admired, she was saddled with multiple crises — the pandemic, enrollment pressures, budget deficits, protests over the Israel-Hamas war, lawsuits and demonstrations against her housing plan at People’s Park.

“I look at it as going from an age of resilience to an era of hope,” said Oliver M. O’Reilly, vice provost for undergraduate education.

Shrinidhi Gopal, undergraduate student body president, also said she is optimistic about Lyons and impressed by his track record of integrating the values of diversity, equity and inclusion in the business school. She said student priorities this year were safety and the future of People’s Park, which is slated for student and supportive housing projects after the state Supreme Court removed the final legal barrier to development in June. Gopal said students wanted to continue conversations about the park.

Lyons also won fans at the welcome convocation for new students. After his remarks, the chancellor leaped to his feet to dance with Oski, the Cal Bears’ mascot, drawing roars from students as the marching band played on.

“We loved your dance!” one student told him.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.