At the Shady Lane Apartments in the suburbs east of San Diego the carpet could be worn, the appliances old. But with some of the cheaper rents around, the complex was a relatively affordable home for an increasingly priced-out working class.

Then, in 2021, the nonprofit that owned the 112-unit property sold it. In just under three years, the new owners raised rent for vacant units 21 percentage points more than landlords in nearby neighborhoods, according to data from a real estate research firm. On average, available homes at the complex went from less expensive than the surrounding area to more expensive.

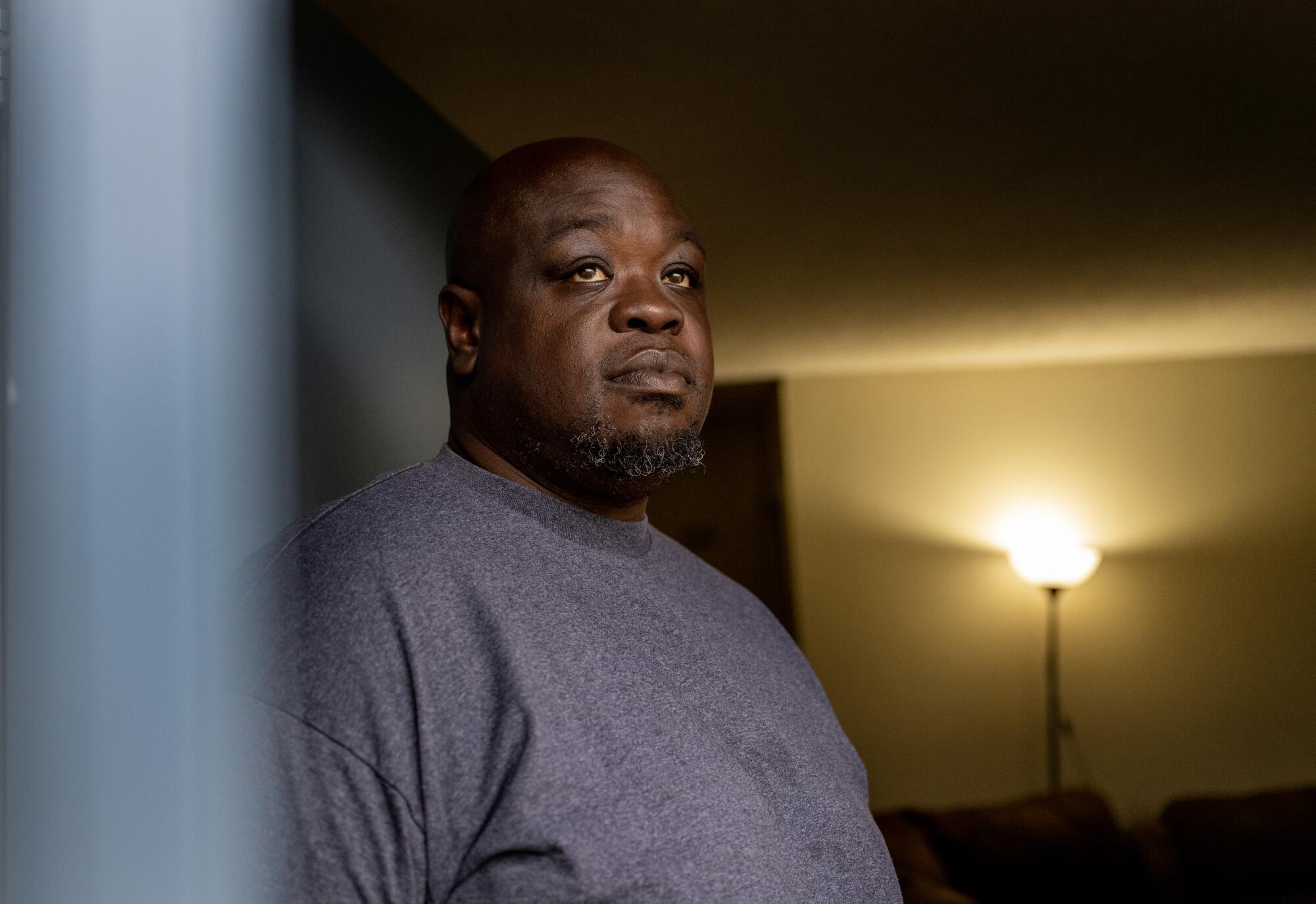

Existing tenants saw change too. Rubin Flournoy, a supervisor at a city water treatment plant, said he’s seen his rent climb roughly twice as much annually since the sale. What he didn’t know was that the new owners had a surprising funding source: people like himself.

The El Cajon complex had been sold, according to research firm CoStar and commercial loan reports, to a giant real estate investment fund managed by the private equity firm Blackstone. Investors in the fund include the California State Teachers’ Retirement System and other public pension systems across the country.

“I didn’t know that [public pensions] did these types of investments,” said Flournoy, a member of the San Diego City Employees’ Retirement System. “I mean, I am being affected because somebody else’s pension is doing it. So I’m quite sure that my pension is doing the same thing to somebody else.”

Across the country, public pension systems are pouring billions of dollars into higher risk real estate investment funds that are managed by private companies and target outsize returns. Investment experts say the trend is driven by a variety of factors, including a long-running goal of portfolio diversification and a more pressing need by underfunded public pension systems to boost returns to pay members what they’ve promised.

Such pension investment in multifamily housing increased nearly sevenfold between 2011 and 2023, according to one measure tracked by consultancy Ferguson Partners.

But while the investments are aimed to beef up pension plans that teachers and other public employees rely on when they retire, critics of these higher risk real estate funds say their very design encourages gentrification. Interviews with tenants and an L.A. Times analysis of industry rent data show the funds often sharply hike rents, squeezing some of the same middle-class workers that pension systems are meant to benefit.

Flournoy’s retirement system, for example, committed $30 million to a fund managed by real estate firm Waterton that in 2021 purchased the Vue high-rise apartment tower in San Pedro, according to CoStar. Waterton then raised the average asking rent nearly 19% — compared with a 10.4% increase in the surrounding area.

“The cost of living is ridiculous,” said Erich Tran, who along with his partner Tyler Bahr experienced a nearly 6% rent increase last year that brought the cost for their one-bedroom in San Pedro to nearly $2,500.

A year earlier, rent had risen nearly 8%.

Since 2011, higher risk real estate funds have purchased more than 1.4 million apartments across the United States, according to CoStar.

The data service does not track how many of those funds received money from pension systems, but does have data on rent in individual properties.

Using CoStar and a separate database that tracks pension commitments to investment funds — PitchBook — The Times analyzed rental trends at 133 properties in California that were acquired by higher risk investment vehicles that received commitments from California pensions over an eight-year period ending in 2022. These include the statewide megafund for public school teachers, CalSTRS, along with local retirement systems for government employees in Los Angeles, Orange County and San Diego.

Overall, average rent rose 7.7 percentage points more at the pension-linked buildings than the surrounding neighborhoods, according to a Times analysis of data from real estate firm CoStar. Nearly 40% of properties saw rent rise at least 10 percentage points more.

In a statement, CalSTRS said it “acknowledges the challenges surrounding affordable housing” and that “our approach to investing in real estate reflects our mission to ensure a secure retirement for California’s public educators. “

CalSTRS pointed to investments it has made in both income-restricted affordable housing and new construction, which expands supply. But the retirement system declined to answer specific questions about its investments in riskier funds that have acquired existing, non-income-restricted apartment buildings.

The San Diego City Employees’ Retirement System — which invested in the fund that CoStar shows purchased Tran’s apartment building — declined to comment.

Under state law, landlords can evict tenants if they are planning a “substantial remodel” of a unit. Long Beach housing advocate Maria Lopez saw it as a loophole in tenant protection law.

Blackstone and Waterton declined to say if individual California public pensions have earned or will earn a return off the buildings CoStar and other sources show the funds acquired. In general, industry experts said that if pensions or other investors commit money to such funds, they receive a return based off all properties the funds acquire.

Michael Reher, an assistant professor of finance at UC San Diego’s Rady School of Management, has studied pension housing investments and reviewed The Times’ findings. It “certainly seems like this would be exacerbating the affordability crisis,” he said.

The data tracked by The Times covers rent for available units and thus show an increase in housing costs for people looking for a new place to live. Several tenants also told The Times their rent climbed faster once the pension-linked funds in The Times’ analysis took over.

At the Vue in San Pedro, Bahr said the couple’s last two rent increases, at $139 and $172, were more than three times what he recalled was common under the previous owner.

The escalating rent had an impact. Bahr stopped putting money into savings and the couple decided to call California quits all together.

This month, they gave up their $2,465 one-bedroom and moved to Texas.

“It’s been on my mind for a few years,” Bahr said. “I need to be able to afford to have a roof over my head.”

If they chose to stay another year at the Vue, Waterton was set to raise their rent again, this time nearly 7%, to $2,633, according to a renewal letter.

As of Tuesday, Waterton was advertising the unit, available in September, at just under $2,900 a month for a one-year lease.

‘Mercenary’ investment strategies

Over the past decade and a half, capital of all sorts has flooded real estate, at times helping to send prices higher.

In a search for higher returns, institutional investors such as pensions and insurance companies pumped money into big funds run by private equity and other firms that became ever-larger landlords.

The companies offer funds tailor-made to a specific risk strategy. “Core” funds target the lowest return with the lowest risk, “value-add” carries the promise of greater return with greater risk, while “opportunistic” is the riskiest of all, a gamble with hopes that it would be rewarded with the highest payout.

There are no definitive rules about what each strategy entails. But when buying existing apartments, investment experts said, core funds typically buy top-performing properties and may not raise rents any more than previous owners.

Value-add and opportunistic funds — those The Times included in its analysis — “are a little more mercenary,” said Jeffrey Hooke, a senior lecturer at Johns Hopkins University and former private equity executive. “They’d be more open to kicking out poor people and jacking up rents.”

John Drachman, co-founder of Waterford Property Co. in Newport Beach, previously executed value-add apartment strategies on behalf of investors. He said he stopped because not only is such investment too risky, but it often negatively impacts lower- and middle-class tenants.

To earn the high returns opportunistic and value-add funds target, it’s generally necessary to increase rent more aggressively than is typical across the marketplace, Drachman said.

“You can not decrease expenses enough to justify that level of return,” said Drachman, who also teaches real estate entrepreneurship at USC.

To achieve needed rents, experts said, these riskier funds often take dated buildings with relatively low rents and remodel common areas and vacant apartments to attract new tenants who will pay more, with the renovations ranging from superficial to extensive.

Changes don’t stop there. Drachman said fund managers want to aggressively push rents higher on existing tenants too. If tenants accept the hikes and stay, owners bring in more cash than they were without spending money on new flooring and appliances. If they move out, owners can renovate and charge even more.

As apartments become pricier, the extra rent not only brings in more revenue, but it raises the value of the property, which is supposed to generate outsize returns when investment managers sell it, often after several years.

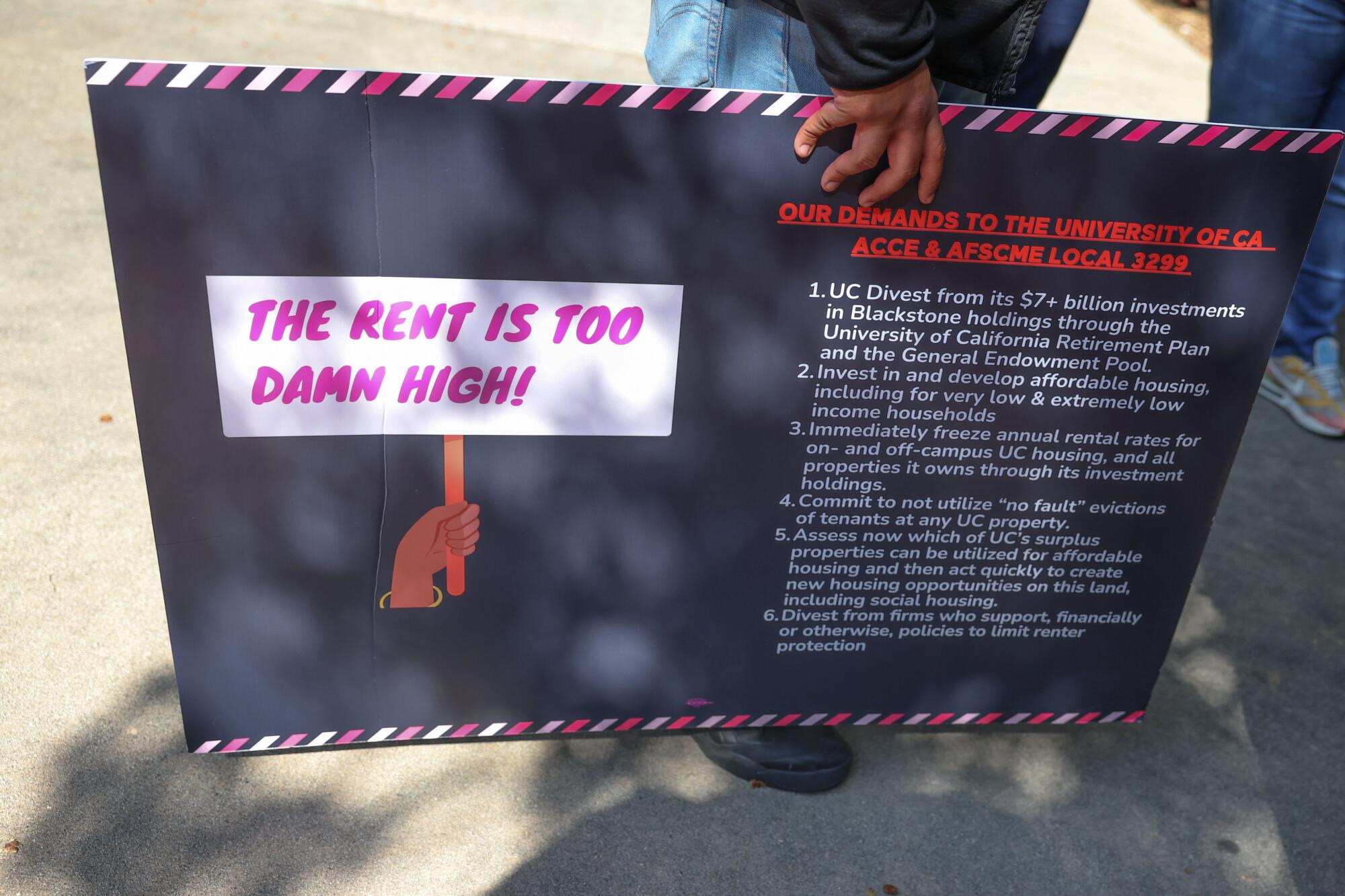

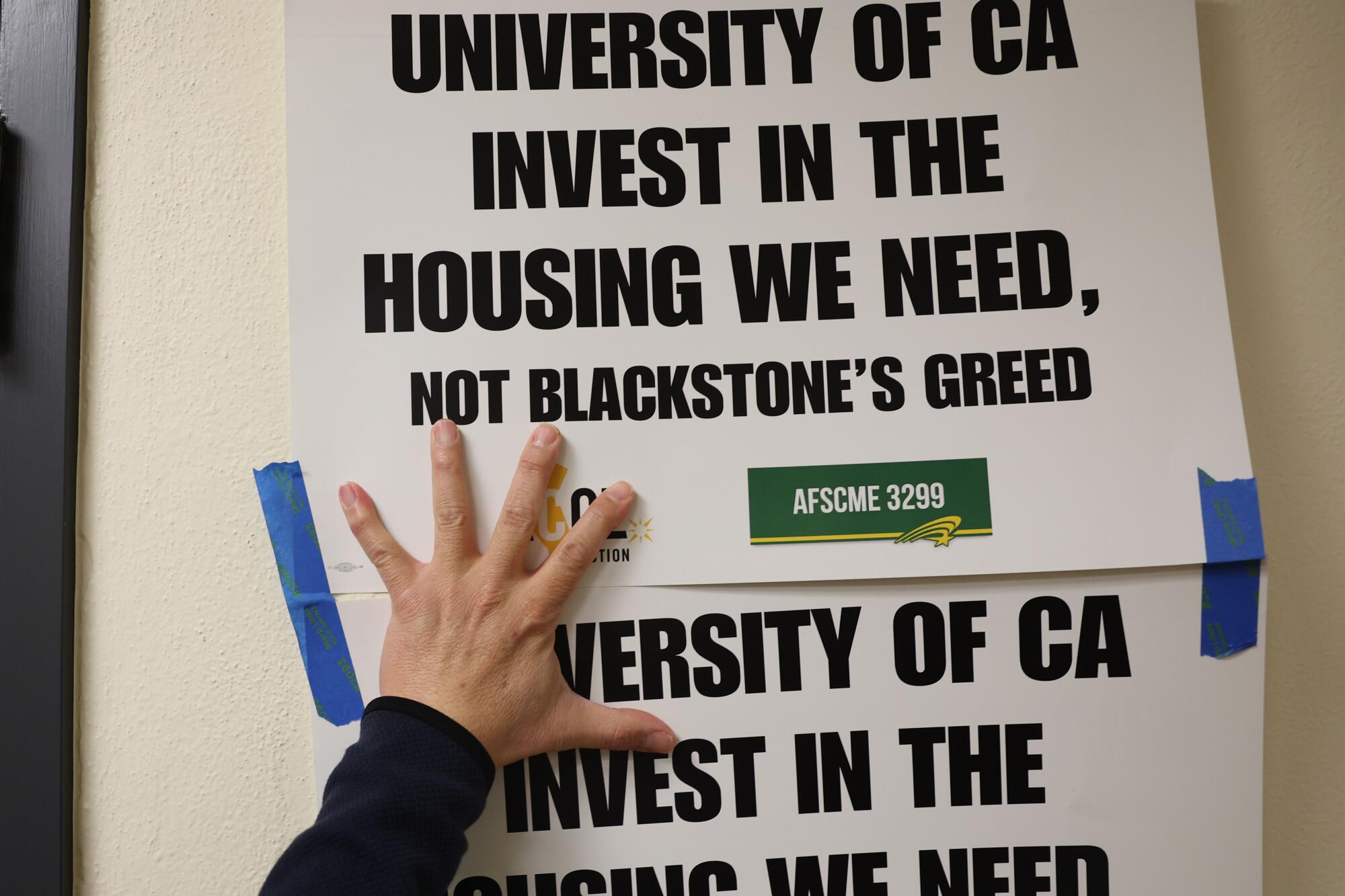

“This is very clearly reducing the supply of housing at a particular affordability level,” said Amy Schur, campaign director for Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, which is helping to organize Blackstone tenants. “When pension funds invest in high risk portfolios of Blackstone and others like them, what they are ... doing is fueling gentrification.”

Maria Merritt has faced addiction, death of loved ones and other tragedies. A publicly owned home in El Sereno she had, lost, then regained gives her the strength to go on.

In the case of the Shady Lane Apartments, CoStar data show an opportunistic fund from Blackstone purchased the complex and more than 5,500 other units across San Diego County from the Conrad Prebys Foundation, a longstanding nonprofit organization. More than 20% of commitments to the fund came from public pensions, according to a Times review.

Since the acquisition in 2021, Blackstone has rebranded many of the communities and, according to interviews with existing tenants, renovated units after they became vacant.

At the newly branded Terre at Madison, formerly Shady Lane, a property website shows photos of remodeled apartments with new flooring and spotless white walls, while boasting of “thoughtfully designed” living spaces that are “stylishly appointed with the kind of premium materials and finishes you won’t find in any other apartments for rent in El Cajon.”

Several checks of the website this year showed the cheapest available two-bedroom apartments ranged from $110 to $506 more expensive than what Flournoy currently pays for the same size unit.

It took the new owners over two years to replace the tattered brown carpet, rusty refrigerator, stove and aging countertops in his apartment, he said. While he waited for those improvements, his rent climbed several hundred dollars.

Last week, he signed a lease renewal that will raise his rent another $174 a month come September, a bump of 8.6%.

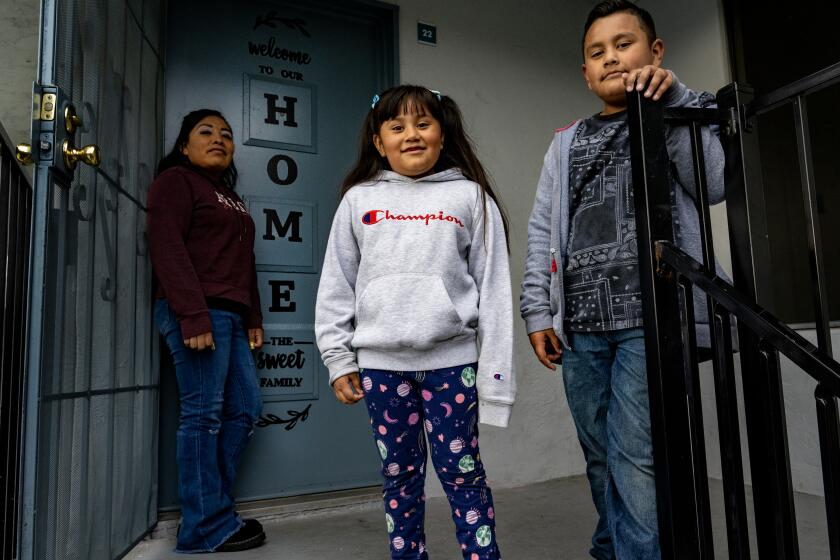

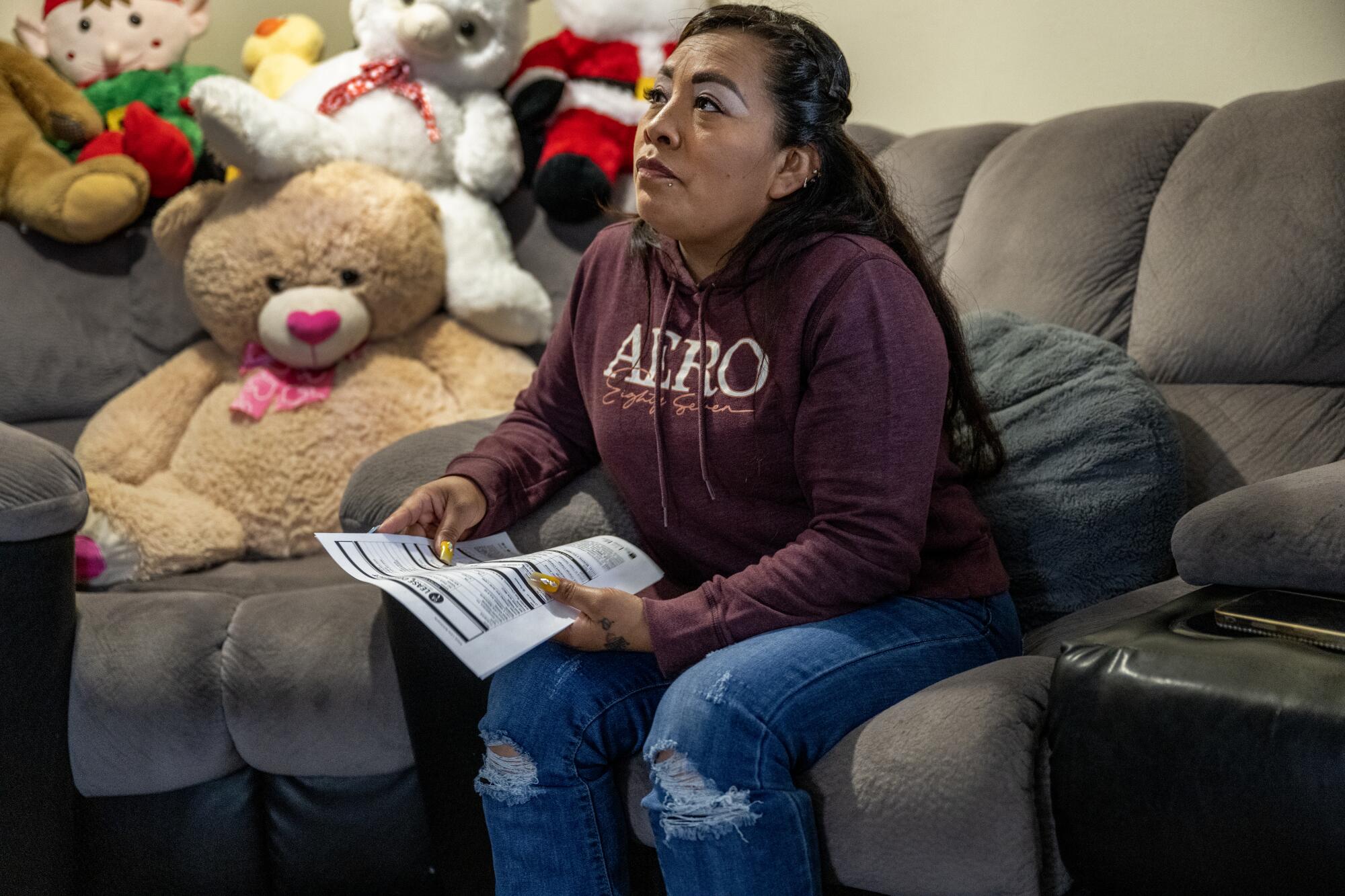

Upstairs, Iraides Gonzalez said the three-bedroom apartment she lives in with her three children and two roommates has not been renovated. Last year, her rent increased by $218 a month, according to lease documents she shared, double what she said was normal under the old owners.

“It’s unjust,” the 37-year-old restaurant worker said.

To afford the extra rent, the single mother said, she started working six days a week and cut back on spending, including putting off trips to the beach with her children and visits to the orthodontist for her teenage daughter, Brianna.

Prior to Brianna’s 15th birthday last year, her mother said, her daughter asked her not to spend money throwing her a quinceañera. What she really wanted was something Gonzalez had to tell her wasn’t possible: a room of her own.

“I would like to tell her yes,” Gonzalez said in Spanish last year. “But unfortunately it’s not within my reach.”

In written responses to detailed questions, Blackstone said a lack of housing construction, coupled with high demand, is the driving factor pushing rents higher, not its investments, which currently account for less than 1% of all rental housing in the U.S.

At the San Diego properties, Blackstone said the majority of units remain “affordable for those earning the area median income” and that since acquiring the properties it has invested about $100 million to “make them better places to live,” completing more than 41,000 repairs.

Blackstone said that despite rent increases, Gonzalez and other tenants interviewed pay “significantly below market.”

“We aim to provide the best experience possible for our residents,” the company statement read. “It benefits our investors to have happier residents that stay in their homes.”

In response to The Times’ findings, Blackstone officials said in a statement that the paper’s analysis was flawed and relied on “incomplete, cherry picked data that significantly overstates actual rent increases” for Terre at Madison and another property in its portfolio. Blackstone declined to elaborate.

CoStar wasn’t the only data provider that showed similar trends. Moody’s Corp. also said rent at the two Blackstone properties in question climbed more than the submarket.

While The Times’ analysis focused on California properties and California pension funds, value-add and opportunistic funds receive money from retirement systems across the country and buy properties outside California as well.

Waterton, based in Chicago, has a portfolio from coast to coast. In a 2020 presentation to a Connecticut investment council, the company encouraged the state’s pension system to invest in the value-add fund that would later purchase the Vue in San Pedro, according to CoStar.

In the pitch, Waterton said it seeks to carry out “cost-efficient renovations to improve property performance and drive investment returns” and noted it used “rent optimization software” to “maximize rents and occupancy.”

In a statement, Chief Executive David Schwartz said Waterton’s value-add investments are beneficial. The company improves common areas, fixes plumbing, roof and other building deficiencies and renovates apartments when people move out.

“Without this investment strategy, much of the existing housing stock across the country would go into disrepair, become obsolescent, and in some cases become unlivable,” Schwartz said.

Such investment is supported by increasing rents. While rent growth varies by community, at Waterton’s California properties it has been “in line” with the general market, according to Schwartz.

Waterton declined to share the data.

When it comes to high housing costs, many economists agree the driver is a lack of supply that enables both home sellers and investors to demand higher sales prices and rents. In fact, Waterton and Blackstone have cited housing shortages as reasons institutions should invest in their value-add and opportunistic funds.

Richard Green, director of the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate, said there typically is a trade-off for such investments. “The upside is it’s a better building and the downside is it’s less attainable,” he said. “Better quality housing is more expensive.”

Shift toward real estate

Public pensions collect contributions from workers, local government employers and sometimes the state, and invest the money with the hope of earning enough to pay workers when they retire.

If returns aren’t enough, governments could be forced to step in and help cover the difference.

Prior to the 1980s, public pensions focused the vast majority of their funds on conservative investments such as government bonds, according to research from the Pew Charitable Trusts. In recent decades, they’ve dramatically increased real estate investment.

How we reported the story: Public pensions invest in ‘mercenary’ funds that buy apartments and hike rent

As investment theory increasingly emphasized diversification, real estate became an option that could protect against inflation, pose less risk than stocks and wouldn’t rise and fall with other investments. It also provided strong returns as other options like bonds struggled in the low-interest rate environment of the past two decades.

Apartments have proved particularly attractive in part because a supply shortage helped drive rents up sharply after the Great Recession and provided pensions an opportunity to capture the winnings.

From 2011 through last year, public pensions committed a total of $52.8 billion to privately managed funds dedicated specifically to multifamily housing — nearly 39% of which was in riskier value-add and opportunistic strategies, according to data from Ferguson Partners.

Investment peaked in 2022 and fell back last year as rising interest rates chilled the real estate market. Even so, pension commitments to value-add and opportunistic multifamily funds last year were $2.3 billion, nearly seven times higher than 2011, the data show.

The multifamily figures don’t include large, diversified real estate funds that purchase apartments along with other property types such as warehouses and malls.

One of those is the opportunistic fund that, according to CoStar, acquired the San Diego properties: Blackstone Real Estate Partners IX. At $20.5 billion, the company described it as the “the largest real estate fund ever raised” at the time fundraising wrapped in 2019.

According to research from Reher, the UCSD professor, from 2009 to 2016, public pensions accounted for 33% of investors in value-add and opportunistic funds that solicited money from multiple sources and invested it for a limited time period, which is the type of fund in the L.A. Times analysis.

Ideally, pensions would invest only in safer, long-term real estate strategies that aren’t dependent on rapidly increasing rents and getting out relatively quickly, said Anthony Randazzo, executive director of the Equable Institute, a nonprofit that seeks to improve the financial health of public retirement systems.

But many pensions are seriously underfunded, a problem that emerged in the 2000s when, following years of expanded benefits, the dot-com bust and then the Great Recession hammered the value of pension assets.

Randazzo said safer investments alone don’t earn enough to backfill underfunded liabilities and could require governments — potentially at their own financial risk — to increase contributions to plug the hole.

“They are really, really hoping that they can ... magically invest their way out of this,” Randazzo said.

Many bought homes in recent years, aiming to lower payments by refinancing once interest rates dropped. With borrowing costs still high, those plans are on hold.

According to The Times’ analysis, not all 133 properties reviewed saw rent climb faster than surrounding submarkets’.

Rents rose more slowly than nearby apartments in nearly 35% of the buildings, The Times found.

Investment experts said that may have happened for several reasons. Owners may not have yet started renovations or they could have acquired the property at a deep discount — maybe out of foreclosure — and didn’t need to raise rent as much to earn their return.

Hooke, the former private equity executive, had another theory. After all, while landlords have the power to raise rents, tenants can go elsewhere.

“It’s not a risk-free proposition doing opportunistic real estate or value-add,” Hooke said. “I think they screwed up.”

The Los Angeles City Employees’ Retirement System and the Orange County Employees Retirement System declined to comment on The Times’ analysis, as well as their investing in value-add and opportunistic funds.

UC Investments, which oversees the University of California’s pension plan that invested in the Blackstone opportunistic fund, similarly declined to comment.

Jim Baker, executive director of the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, said pensions have a responsibility to use members’ money in ways that will not hurt them or other working people.

He said The Times’ findings — as well as a similar analysis from his organization — indicate people have been negatively impacted and called on all pensions to adopt specific standards when making housing investments, including a 3% rent cap and quick turnarounds for repairs.

Given the size of California public pensions, he argued that if they adopted such policies it could change how private equity firms invest in housing nationwide and thus lead to better outcomes for tenants.

“It’s a massive amount of money,” he said. “It could move the market.”

The risk

Blackstone is one of the largest money managers in the business.

In its statement, the company said it invests “on behalf of pension funds that provide retirement benefits for over 90 million teachers, firefighters, nurses and others.” Since starting its opportunistic real estate fund series in 1991, Blackstone said it has generated net returns of 15% for “those pensioners and retirees.”

That return level meets the target CalSTRS aims for in its opportunistic real estate investments, but such deals don’t always turn out so rosy.

Timothy Riddiough, a professor at the Wisconsin School of Business, said value-add and opportunistic funds generally target returns of 13% to 20%. But in reality, the funds have achieved only a 10% return on average, according to his research with colleague Da Li that covered funds launched between 1980 and 2014.

Given current turmoil in the real estate market, Riddiough said, he expects real returns to fall further.

“The private equity business — the Blackstones of the world — have been very effective at selling to investors that, well, every time there’s a downturn, ‘Look, we’ll just form a new fund,’” Riddiough said. “‘The existing funds aren’t doing so great, but look, we’ll form a vulture fund and really take advantage of the situation.’”

In April 2023, Blackstone announced the $30.4-billion Blackstone Real Estate Partners X — nearly $10 billion larger than Blackstone’s previous fund that acquired the San Diego properties, according to CoStar.

As the private equity firm works to spend those dollars, the impacts of previous deals reverberate.

Back at Blackstone’s Terre at Madison complex, Iraides Gonzalez received an even larger rent increase in April — $242 a month — and now pays $2,667, according to lease documents. Around the same time, she said, her boss reduced her hours because of a slowdown at her restaurant.

In a June interview, Gonzalez said she isn’t sure how she’ll pay rent long term. So far she’s squeaked by with money borrowed from her employer.

Times staff writer Paloma Esquivel contributed to this report.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.