Navy exonerates Black sailors punished after 1944 Port Chicago explosion

More than 250 Black sailors, punished for refusing to return to dangerous work after a powerful munitions explosion in Port Chicago killed 320 sailors in 1944, were fully exonerated by the Navy on Wednesday.

The exoneration came on the 80th anniversary of the tragic explosion during World War II, and followed decades of petitions and requests by family, advocates, and historians who argued the 258 sailors who refused to go back to work were subjected to racism and unfairly targeted and court martialed in the segregated Navy.

The explosion was the “deadliest home-front disaster in the U.S. during World War II.”

In a statement, President Biden said the decision “is righting an historic wrong.”

“Today’s announcement marks the end of a long and arduous journey for these Black Sailors and their families, who fought for a nation that denied them equal justice under law,” Biden said in the statement.

While white supervising officers were given hardship leave after the blast, surviving Black sailors were ordered back to work loading ammunition on ships and cleaning up the carnage left behind from the blast.

The U.S. military was segregated at the time and most of the sailors loading and unloading ships in Port Chicago at the time were Black. Of the 320 who were killed, 202 were African American, according to the National Park Service, which oversees the memorial at the site of the explosion.

In an interview with the Associated Press, Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro called it “a horrific situation for those Black sailors that remained.”

Located on Suisun Bay, the naval barracks at Port Chicago began being planned just after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941, according to naval historians.

Leading up to the explosion, sailors had warned about poor conditions at the port.

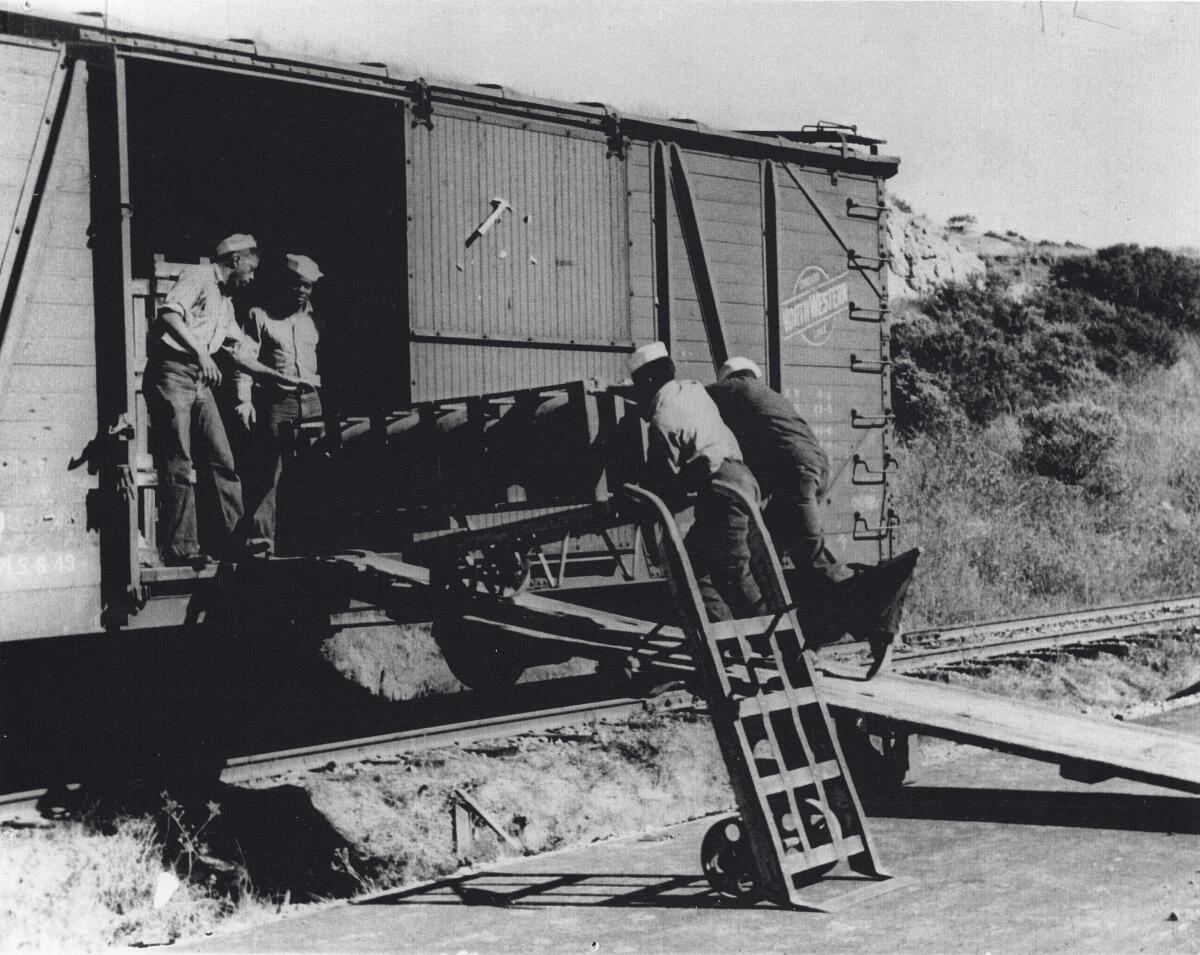

Naval historians noted the sailors assigned with the grueling work of loading ships with munitions for the war were poorly trained, faced hazardous working conditions, low morale, and increasing quotas that demanded round-the-clock work.

Then just after 10 p.m. on July 17, 1944, there was a massive explosion of munitions while the SS Quinault Victory and SS E. A. Bryan were berthed at the pier.

The cause of the explosion was never determined.

Less than a month after, Black sailors were ordered back to work without adequate training or protective equipment.

The 258 men who refused to go back were confined for three days on a barge.

The sailors were tried and convicted in a court martial, sentenced to bad conduct discharge and fined three months pay. Fifty of the men were identified by the Navy as leaders, and were charged with conspiring to commit mutiny. They were convicted, sentenced to 15 years in prison and dishonorably discharged.

The treatment of the Black sailors then, and for decades following the deadly explosion, highlighted the racist treatment of Black members of the military.

Naval historians noted, for example, an investigation into the explosion focused on the challenges faced by the mostly Black workers on the ground, and blamed the lack of training to racist tropes against the Black sailors.

“The report raised no questions concerning the white officers’ leadership responsibilities,” according to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

During the military trial, then Chief Consul for the NAACP Thurgood Marshall held news conferences outside the proceedings where he spoke out against the discriminating actions.

Marshall, before becoming one of the most well-known Supreme Court Justices in history, wrote that “justice can only be done in this case by a complete reversal of findings.”

The NAACP continued petitioning for the exoneration of the sailors for decades, including sending a resolution to the Secretary of the Navy in 2023 calling for the exoneration of the sailors.

On Wednesday, Del Toro told the Washington Post the decision came after a Navy investigation found legal errors made in the 1944 courts-martial.

The finding to exonerate the sailors, he told the Post, “clears their names, restores their honor and acknowledges the courage they displayed in the face of immense danger.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.