Ellen DeGeneres skipped onstage for her talk show that day, beaming, proclaiming: “I can’t even tell you how excited I am.” The comedian and her wife had adopted a puppy, a chocolate-brown poodle named Mrs. Wallis Browning.

“We got her from a wonderful rescue place,” she told the audience in 2019. “It’s called Wagmor.”

Just that quickly, Wagmor Pets became famous.

The fledgling, little-known organization soon found dogs for Jennifer Aniston, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson and other celebrities. Local news began showing up at its Studio City location to interview the founder, Melissa Bacelar, a former scream queen actor.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“There are shelters everywhere that are full, that are turning away dogs,” Bacelar would say. “So you have to rescue.”

All this publicity translated into big business — hundreds of adoptions a year — but other rescue groups grew concerned.

The issue? Along with a predictable assortment of mutts, Wagmor seemed to have a lot of puppies, purebreds and popular doodle mixes, the kind not always found in shelters.

Some customers also grew skeptical, filing a series of lawsuits that, among other things, claimed Bacelar was buying dogs on the cheap from breeders, then misrepresenting them as rescues and charging high adoption fees. Former employees interviewed by The Times echoed these claims.

“It started out kosher,” says Faith Ballin, an ex-assistant manager. “We saw it completely go down and turn into something else.”

Bacelar denies the allegations, insisting that all of her dogs qualify as rescues because they are animals in need. She also denies ever buying from breeders. Bolstered by an army of supporters and Instagram followers, she has filed a defamation suit against several of her loudest critics, saying: “I don’t know if it’s jealousy. Maybe it’s because I have a business mind and I’m good in front of a camera.”

The Wagmor controversy isn’t just a matter of squabbling about the right way to save animals. It shows how California — struggling with an overpopulation of strays — has failed to regulate private rescue groups, allowing them to operate outside the sphere of municipal shelters and set their own rules.

“It has gotten so crazy,” says Madeline Bernstein, president of SpcaLA. “There is a lot of game playing with that word, ‘rescue.’”

Rescue groups tend to get dogs from the streets, overcrowded shelters and owners who surrender pets they can no longer keep. These methods are widely accepted.

But should buying a purebred from a breeder — even an irresponsible one — count as a rescue? What about purchasing at auctions where puppies are treated as a commodity? Or importing strays from other states?

“It’s a debate that happens among us all the time,” Bernstein says.

The distinction matters to private groups whose work can be frustrating. They often keep animals in their homes and must scramble for donations because the nominal fees they charge don’t cover food or veterinary bills. Some of their older mutts might never get adopted.

The possibility of purebreds going to people who want to adopt, who might otherwise take a less fancy dog, angers many in the field who confront such challenges.

California ranked among the national leaders with about 27,000 dogs euthanized last year, according to the Shelter Animals Count database. In shelters operated by Los Angeles County, euthanasia rates have run as high as 35%.

The county’s Palmdale Animal Care Center was supposed to be a cutting-edge shelter that would relieve overcrowding and reduce euthanasia. But that’s not how it’s turned out.

Most of the laws addressing this crisis focus on breeders. The state has banned them from selling in pet stores — which can now display only rescues — and the city of Los Angeles has placed a moratorium on new breeding permits. Private rescues face less oversight.

These groups can be cited for abuse or other violations, but do not have to obtain a license or register with municipal shelters. They can choose whether or not to be nonprofit. Patti Strand, president of the National Animal Interest Alliance, calls it “totally unregulated commerce.”

Amid this Wild West environment, Bacelar sees herself as a scapegoat.

Wagmor has been sued more than a half-dozen times in recent years, she says, accused not only of misrepresenting breeder dogs but also failing to adequately care for puppies that fell seriously ill immediately after adoption.

Bacelar denies these allegations but acknowledges that the state attorney general’s office, which declined to comment, is investigating her business practices.

All of this she blames on rivals and detractors, claiming they have repeatedly doxed her and made anonymous death threats.

“They say all these crazy things,” she says. “They are harassing us.”

Saving dogs was not why Bacelar came to L.A.

With long, blond hair and an outgoing demeanor, she moved here about 20 years ago to act in horror films such as “Skinned Alive,” “Pink Eye” and “Zombie Ed.” There was a dog chained outside an apartment building, day after day, in her neighborhood; she took it to a local rescue and was inspired to foster.

Next came a stint as a pet psychic — “I’m just very spiritual, right?” — and a first attempt at starting a rescue. She left the organization in 2013 over disagreements with her partners, who were later convicted of abuse for hoarding dogs and cats. Bacelar was not named in the case.

After trying and failing to open a gelato store, she pivoted to selling organic pet food and keeping a few rescues in a small shop on Ventura Boulevard. The rent was pricey but the location was perfect.

“The second day, this woman walks in and there’s paparazzi, you know, and it’s Miley Cyrus,” Bacelar says. “Then, on day three, it’s Sarah Hyland.”

Celebrity customers brought free publicity, helping Wagmor boost its adoption numbers and move across the street in 2015.

The new space had a lobby big enough for a counter and an old couch. In the back, a large room was partitioned into pens where dogs could amble around, play or sleep on scattered beds. As word continued to spread through the Hollywood crowd, Bacelar says she got a call from DeGeneres.

The talk show host, who did not respond to interview requests, wanted to rescue a certain kind of dog, so Bacelar went looking for a female, purebred, hypoallergenic puppy. Another group says it, too, was notified and began scouring local shelters.

It was a tough ask, but Bacelar found a batch of poodles that fit the bill. DeGeneres, Chrissy Teigen and Kris Jenner each took one home.

“If a celebrity calls and asks for a specific type of dog, all of a sudden that dog turns up the next day?” asks Kim Sill, a veteran Southern California rescuer. “That does not happen with regular rescues.”

Bacelar offers an explanation: She recalls scanning a Facebook group for poodle lovers and coming across a local breeder who no longer wanted two adult dogs and eight offspring from separate litters. “I will never forget because they gave me a location to meet them,” she says. “I mean, it looked like a desert, like it was a parking lot in the middle of nowhere.” Saying that no money changed hands, she calls it a rescue.

“The Ellen DeGeneres Show” began featuring Wagmor in recurring segments. Then COVID-19 hit, trapping people at home and triggering a rush on pets.

“I think Jennifer Aniston had adopted from us and a couple other [celebrities], so we had a decent Instagram following of 20,000 people,” Bacelar says. “We would post the dogs for adoption, and my overnight guy called me one night at 4 a.m., and I’m like, ‘What’s going on?’ We don’t open till 9, but he says all these people are lined up in front of the store.”

Much was changing at Wagmor. The group soon touted 1,000 or more adoptions a year, an eye-popping number that included both purebreds and run-of-the-mill mixes. According to four former employees who spoke with The Times, Bacelar started making demands.

Francesca Bucci, an assistant manager in 2020, says the boss wanted dogs that would keep customers lining up and command fees as high as $1,500 or more — well above the standard $300 to $500.

“Floofy or young,” Bucci says. “It got to the point where she told me I had to scour Facebook Marketplace and Craigslist for puppies that were available for purchase.”

Bucci says she arranged a dozen or so transactions with “backyard” breeders and people whose dogs had accidental litters. She recalls personally buying six pit bull mix puppies for Wagmor from a Palmdale seller.

“We were purchasing these dogs and selling them off,” Bucci says. “If people asked, [Bacelar] would say they were owner surrenders.”

Bacelar denies pressuring employees to buy high-value puppies, saying only that she occasionally paid $25 to $75 to remove dogs from inhumane conditions. Still, other groups grumbled.

In 2020, word spread on social media that Bacelar had arranged to buy four golden retriever-rottweiler puppies from a seller in the high desert community of Phelan. Her messages to the seller would later be included in an ongoing class-action suit filed by three customers.

“I’ll take all 4,” she allegedly wrote. “2 for me and 2 for my mom … How much?”

At the time, Bacelar responded to critics on Instagram, saying: “Something that we do that probably isn’t the most popular is we look on Craigslist … and sometimes when we’re talking to people on Craigslist that are selling these dogs, we will tell them anything they want to hear.”

Now she recalls agreeing to pay $800 for the puppies but arriving to find them haggard. She says she threatened to call animal control and took them without handing over any money. Again, she calls it a rescue.

1

2

3

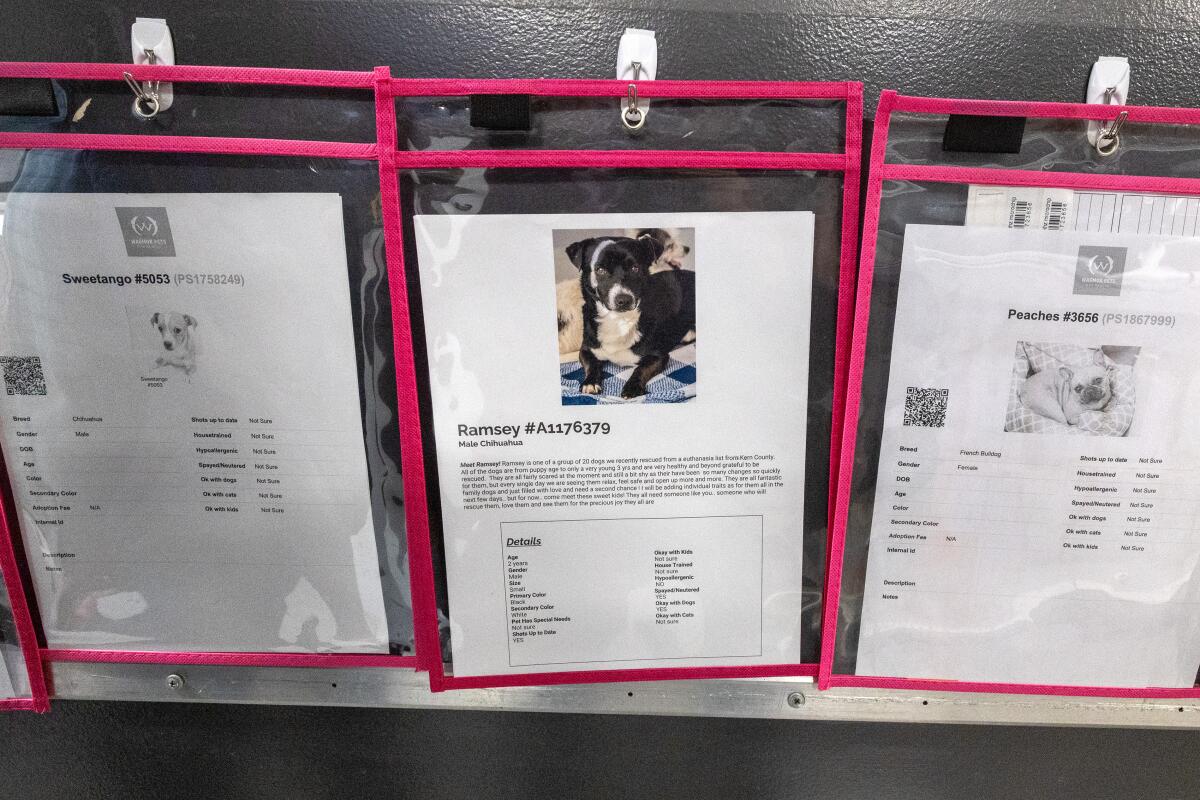

1. Bacelar with a 4-month-old puppy at Wagmor. 2. Pet adoption fliers at the Studio City location. 3. Wagmor rescue manager Sylvia Castro transports a dog. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

The seller did not respond to interview requests.

By 2021, Wagmor’s Instagram account was growing toward a quarter-million followers and, according to federal tax documents, the group was generating more than $600,000 in revenue.

“In my years of dealing with Melissa, never have I called her about a rescue where she didn’t step up to the plate and help,” says Joey Herrick, who owns Lucy Pet products and runs an animal welfare foundation. “She does good work.”

When asked about allegations against her, Bacelar responds forcefully, speaking rapid-fire, sometimes giving conflicting answers. She describes her approach to rescue work.

“When I get goldendoodles, even if they’re in bad shape, that’s my clickbait. I put that dog on Instagram,” she says. “People come to see the goldendoodles and if they’re all adopted, they say, ‘Well, what else do you have?’ So it helps me get other dogs a home.”

This strategy eventually prompted Wagmor to start acquiring purebreds from the Midwest through a process that began with a Springfield attorney named Elise Barker.

For years, Barker has raised donations to buy dogs at auctions throughout the region, saying she wants to remove them from an industry that breeds females repeatedly and sometimes euthanizes unsold animals.

At one of her regular stops, the Southwest Auction in Rocky Comfort, Mo., breeders parade their wares before bidders sitting in rows of metal bleachers. The place smells of urine and feces. Veterinary documents obtained from the state of Missouri show that, over the last year or so, Barker listed Wagmor as the final destination for dozens of dogs she purchased there.

The dogs were given to a Missouri rescue; Bacelar acknowledges sending transporters to pick them up on numerous occasions.

Some people complain that buying from auctions only serves to encourage puppy mills. Barker replies: “My feeling is why blame the victim? These dogs, it’s not their fault.” She says she recognizes that sending dogs to California is also controversial because the state already has more than it can handle.

Animal shelters are dealing with an influx of dogs and cats since the pandemic lockdown, and the overcrowded conditions are leading to higher euthanasia rates.

These debates have not deterred Bacelar. Though she knows about Barker, when the intermediary rescue group in Missouri has animals for her, she says she doesn’t ask where they came from. “I’ve never given anybody permission to buy from an auction,” she says. “If a rescue group buys dogs and needs to place them, I’ll take them.”

Bacelar offers a similar explanation for another issue involving her group.

Last summer, a Southern California family adopted a doodle from Wagmor and, after digging through veterinary records, discovered it came from a professional breeder in Joplin, Mo.

Diamond Doodles owner Colleen Slaughter confirms the puppy was one of hers and says it was among a group of 17 she sold for $1,950 last August. The Times viewed copies of the vet records and a receipt for the transaction, but could not verify the buyer’s identity.

Bacelar acknowledges receiving the doodles in a shipment, but says she didn’t know they came from a breeder, didn’t pay for them and doesn’t know who did.

Animal right advocates propose a way to bring order to the world of rescue.

Create a set of rules for private groups. Check for compliance. Insist upon documentation and transparency so adopters know where their new dog came from.

In Colorado, all private groups must complete online training, apply for a license and file a plan to ensure proper care. The state’s Pet Animal Care and Facilities Act calls for annual inspections.

“I would love to see something like that in California,” says Judie Mancuso, a Laguna Beach activist whose Social Compassion in Legislation group championed California’s pet shop law.

Bacelar is less certain about the need for strict regulation, saying that “we’re all just doing what we think is best.” Having settled a number of lawsuits out of court on the advice of her insurance company, she continues to fight the class-action lawsuit, denying allegations that she has misrepresented dogs and skimped on veterinary care.

The defamation suit she filed is also ongoing, though a judge has dismissed two of the three defendants.

Wagmor supporters characterize the turmoil surrounding the group as rescuers haggling over best practices.

“Their hearts are all in the same place but they go about it in ways that are different,” says Warren Eckstein, host of “The Pet Show” on the Radio America network. “Whenever a group starts getting publicity, there is going to be an onslaught of people who disagree with the approach.”

For now, Wagmor still charges high fees. Bacelar says she needs the money to cover $40,000 in monthly overhead that includes salaries for a 24-hour staff, marketers and social media people to keep her name in the news.

“I want to do whatever it takes to get these dogs and myself, like, a little publicity so these dogs can get more homes, right?” she says.

The group is also seeking donations for another facility and taking more trips to the Midwest, acquiring dogs from the Missouri rescue group that serves as a go-between for Barker.

A recent shipment included more than 40 corgis and other breeds. Wagmor advertised them as rescues on Instagram posts that featured pictures and videos. Potential adopters were encouraged to submit an application.

Times staff writers Alene Tchekmedyian and Melody Gutierrez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.