Column: Five families sued to desegregate O.C. schools. Why is just one remembered?

The 14 people gathered on the steps of the 1st Street U.S. Federal Courthouse in downtown Los Angeles a few Saturdays ago were passionate, but their cause seemed a bit obscure.

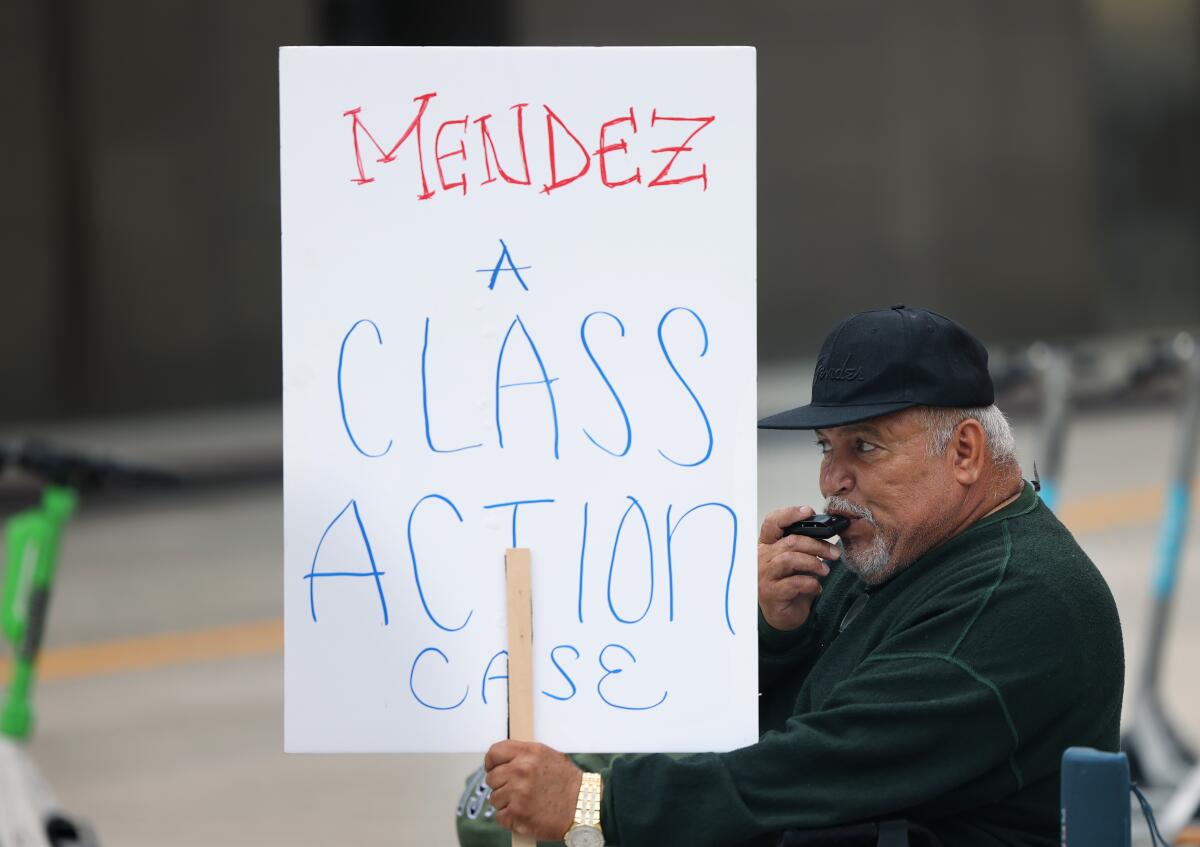

Young and old and in between, with a French bulldog in tow, they held signs that read “Five Families, Four School Districts,” “Et Als Speak Out” and “Omitted Plaintiffs.” They set up banners with photos of their relatives and shouted “Equality!” on a bullhorn to uncaring pedestrians and cars.

Another sign — “H.R. 5754” next to a crossed-out emoji — was equally inscrutable to just about any observer.

Once, the five families — Estrada, Guzman, Mendez, Palomino and Ramirez — were united in their determination to overturn school segregation in Orange County.

They sued four Orange County school districts in 1946, achieving a far-reaching victory that not only allowed local Latino students to attend the same schools as their white peers but spurred the desegregation of schools across California and served as a precursor to Brown vs. Board of Education.

The case was heard at the old federal courthouse on Spring Street. In September, Rep. Jimmy Gomez, a Democrat from Los Angeles, proposed naming the new courthouse on 1st Street after Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez — hence, the bill number H.R. 5754.

“This courthouse will be a reminder that history and law are not just shaped by judges,” Gomez said in a speech last month on the House floor. “They are molded by people who have the courage to challenge unjust laws and make our country better.”

H.R. 5754 passed and is now before the Senate. If it becomes law, the L.A. federal courthouse will become the first named after a Latina, notching the latest triumph in a historical recovery project over the past quarter century that has pulled the class-action lawsuit — Mendez, et al vs. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al — out of the proverbial shadows.

Education: Gonzalo Mendez’s case against Westminster district led to integration of Orange County classrooms 50 years ago.

Documentaries, plays, books, scholarly papers, exhibits and even a postage stamp have commemorated it. A California bill that would require its inclusion in the state’s academic curriculum has unanimously passed the Assembly and Senate.

Gomez’s effort to honor the Mendezes and their place in history seems like the type of feel-good story this country needs more of these days. So who on earth could be opposed to it?

The other four families.

They want the courthouse name to include them, or at least an “et al.”

“Just four little letters — how hard is that?” Mike Ramirez, whose parents Lorenzo and Josefina sued what’s now the Orange Unified School District, said at the protest.

Very hard, alas. Federal courthouses can only be named after municipalities or people — not after court cases.

“It gets you angry,” added 74-year-old Beverly Guzman Gallegos, whose grandparents William and Virginia Guzman sued the Santa Ana Unified School District. She held a framed letter signed by Barack Obama, thanking her family for their role in an important civil rights case.

“These five families were fighting together back then,” said Tammy Guzman. The 50-year-old West Covina resident is married to Amanda Guzman, a great-granddaughter of William and Virginia. “But 75 years later, we’re fighting for inclusion again, this time against one family. I don’t get it.”

“It’s real simple” responded Ramirez. “People take soundbites, and the boisterous ones gets all the attention. History takes it from there.”

The feud between the Mendezes and the other four families goes back decades. Historians and the media focus almost exclusively on the Mendez contribution, the four families argue, starting with how the case is best known: Mendez vs. Westminster, a shorthand that follows legal citation protocol.

They’ve pushed reporters and academics to add “et al.” But most of their ire is directed at the Mendez’s daughter Sylvia.

The 2011 Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient has traveled the country telling the story of how she was forced to attend a run-down Mexican-only school far from her home while her lighter-skinned cousins went to the nearby white school. The other four families? She acknowledges but barely elaborates on them, they claim.

Public schools named after Gonzalo, Felicitas and Sylvia exist from Santa Ana to Boyle Heights to Berkeley and even North Carolina. The only civic commemorations the other families have between them are a library at Santiago Canyon College named after Lorenzo Ramirez and a ceremonial street sign in honor of William and Virginia Guzman that the Santa Ana City Council unanimously approved earlier this week.

I’ve had a front-row seat to this beef for 15 years, ever since I wrote a lengthy story about it. I’ve seen descendants of the four families excluded from events meant to commemorate their relatives’ contributions to civil rights because the hosts were afraid of what they might say. I’ve had to cut some of them short during presentations when their comments about being relegated to historical footnotes got too personal.

On the day of the protest, I had to correct them once more — they first showed up at the courthouse where their desegregation case was heard so long ago, not at the new one that would be named after Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez. Back then, O.C. didn’t have its own federal courthouse, so the families traveled to L.A. for court hearings.

Civil rights history — in Orange County

Their rage might come off as historical sour grapes, but the Mendez et al fiasco touches on an important point. For far too long, American history has operated under the Great Man theory, which posits that brave individuals who beat back haters and doubters accomplish great things, not the masses.

“It’s one of the historical cases that’s most frustrating to me,” said Chaffey College history professor Luis F. Fernández. He has conducted oral histories with members of all the families except the Mendezes, and Mike Ramirez and Beverly Guzman Gallegos have spoken to his classes. “It should be a history of unity — a history of its power, and organizing — in how to defeat a structure that systematically kept Mexican American students out of a pathway. As it is, it’s a chosen, select history.

“I wouldn’t even call [focusing on the Mendez contribution] a history,” the profe added. “At this point, it’s a narrative.”

Fernández has urged the four families to sharpen their strategy by reaching out to politicians like Gomez and U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla, a California Democrat. He also thinks they should stop referring to themselves as the “et als.”

“No one knows what that means,” he said. “It sounds like a tongue twister. Introduce yourselves as one of the families, and get that name recognition.”

Sylvia Mendez didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment, both directly and through a friend.

A Gomez spokesperson sent me a text that read, “Naming this courthouse further enshrines this core part of American civil rights history — that has been unknown by too many for too long — into our national conscience.” The congressmember “proudly names” the Estrada, Guzman, Ramirez and Palomino families alongside the Mendezes “every time he shares this story publicly,” the text continued.

That’s not enough for the four families, whose 1st Street courthouse protest was short but heartfelt.

“It felt insulting” to hear about Gomez’s bill, said 44-year-old Connie Pimentel-Reagins of Murrieta. She’s the great-granddaughter of Thomas and Maria Luisa Estrada, Mendez relatives who also sued the Westminster School District.

“It’s unfair and inaccurate,” said Andrew Palomino, the 53-year-old grandson of Frank and Irene Palomino, who sued Garden Grove Unified School District.

Nearby, 59-year-old Tracie Guzman, Beverly’s niece, held up a cellphone with an NBC News story on the proposed renaming of the courthouse. Only the Mendez family is mentioned. Both the reporter and Sylvia reduced the contributions of the Estradas, Guzmans, Palominos and Ramirezes to the phrase “four other families.”

“It’s always about one family,” Tracie said, shaking her head in disgust. “The Mendezes don’t care. They’re doing good on their own. They don’t need us.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.