The lawyer was expecting assassins. He had purchased a shotgun, in case they burst through his door. He made it a habit to check underneath his car, in case they brought a bomb. He warned neighbors to look out for strangers.

Better than anyone, he was aware of the violent side of the organization he had been challenging in court, of the special hatred borne for him by its increasingly unhinged and paranoid founder, the man who liked to call himself Big Daddy.

But Paul Morantz, 32, was distracted as he arrived at his Pacific Palisades home on the late afternoon of Oct. 10, 1978. The World Series was about to start; the Dodgers were playing the Yankees.

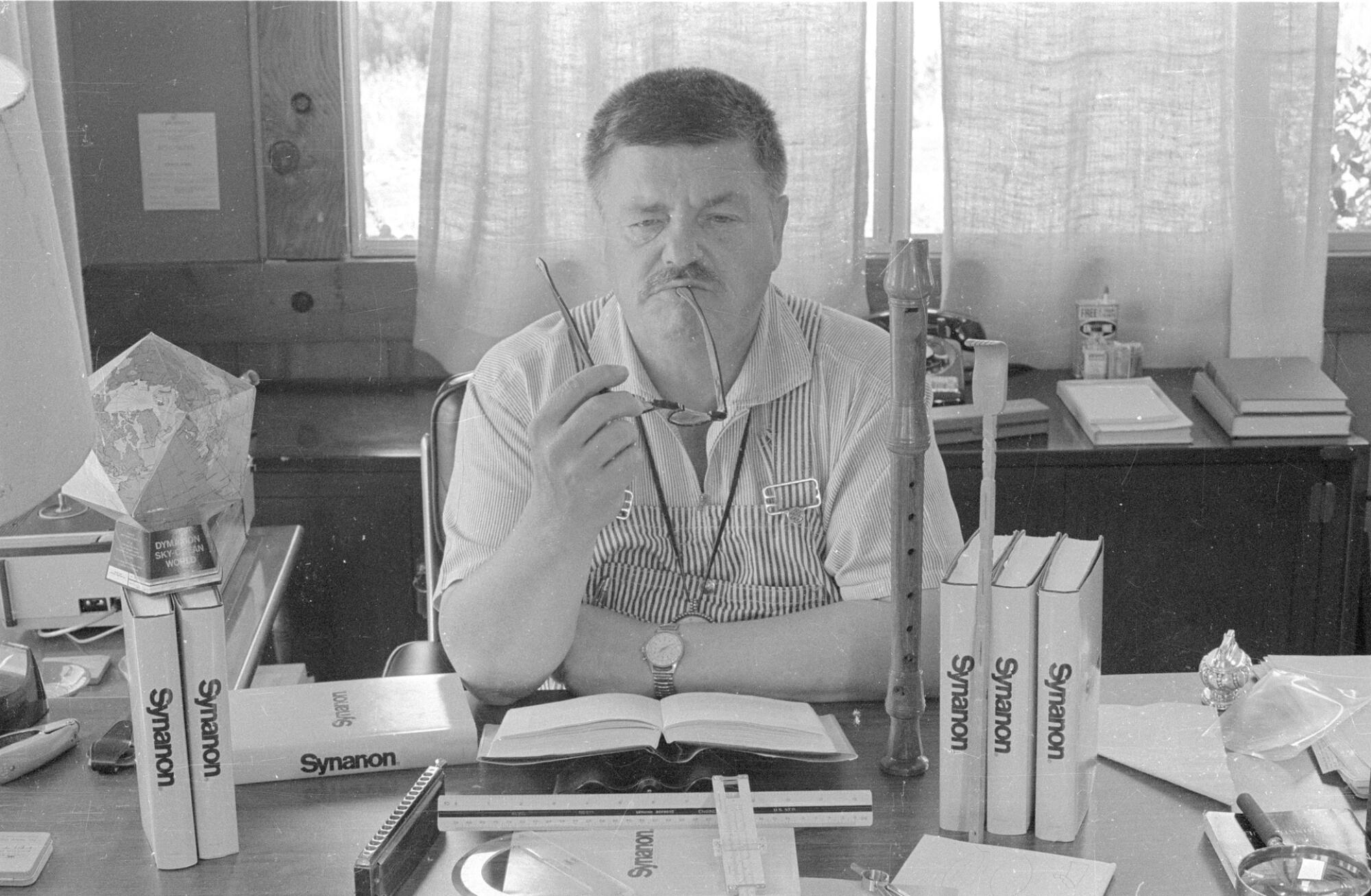

His border collies greeted him at the door. Once inside, he noticed an object through the grill of the mail slot in his living room wall. Some package, he thought as he opened the lid, maybe a scarf. Coiled inside was a 4½-foot rattlesnake. He did not hear it; the rattles had been removed so that he couldn’t.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

There was a sharp pain in his left hand as the fangs penetrated just below the thumb. He watched the snake flop to the floor. He ran outside and began yelling for help. A neighbor brought ice. Another used a shirt to make a tourniquet. A fireman decapitated the snake with a shovel and flushed the head down the toilet.

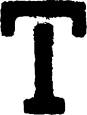

Recovering at USC Medical Center, Morantz was wheeled out in his hospital bed to face the press. He had no doubt the snake had come from Synanon, the drug rehab group founded 20 years earlier by a magnetic pitchman named Charles Dederich.

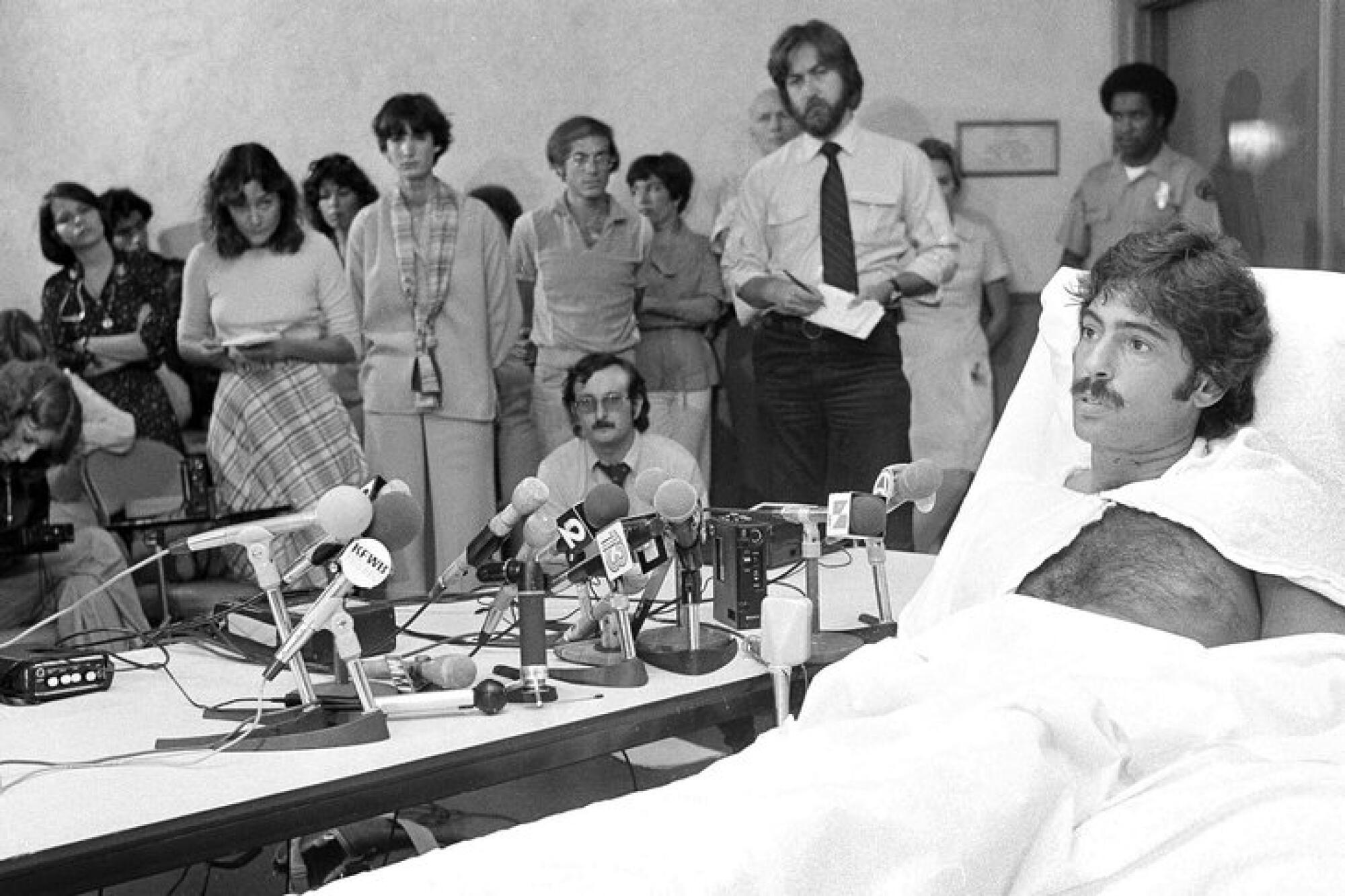

Called Big Daddy, the Chief or the Old Man, Dederich was a recovering alcoholic with a harsh, booming voice and a face half-paralyzed by a childhood bout of meningitis. Since the day he founded Synanon as a home for “dope fiends” in Santa Monica in the late 1950s, he had been its unquestioned leader.

His acolytes became known for their shaved heads and farmer’s overalls. The governing ritual was a form of group therapy called the Game, in which members unleashed verbal attacks on one another. It was supposed to provide catharsis for the emotionally throttled.

Dederich described the Game as “a gimmick that no one else seems to have,” predicated on “uninhibited conversations, yelling, castigation, aggression, lying. Anything goes short of physical violence or threats of physical violence.”

Called the “Miracle on the Beach” by Life magazine, Synanon grew into a multimillion-dollar business and commanded intense loyalty from members, many of whom swore it had saved them from addiction.

But by 1977, the news coverage had become darker and more skeptical. Time magazine was calling it a “kooky cult,” highlighting 64-year-old Dederich’s aggressive push for mass vasectomies and spouse-swapping.

Morantz was one of the group’s most visible critics. He represented a woman who said members had kidnapped and brainwashed her, and he had tried to get Dederich to testify under oath. Dederich refused to submit to a deposition, and the court entered a $300,000 judgment against him.

Morantz had been following reports of violence associated with the group. Members had beaten neighbors near Synanon’s remote mountain compound in Central California. A former member had been attacked outside his home in Berkeley and nearly killed.

Now, speaking to the press from his hospital bed, Morantz ventured a guess about the psychology of his attackers.

“Those people who put the snake in my mailbox do not think of themselves as criminals, I’m sure, but believe themselves to be serving a higher purpose.”

Lance Kenton grew up in Synanon. He was sent there at 11 by his father, jazz musician Stan Kenton, who was frequently on the road and paid the group $750 a month to take care of his son.

As a kid, Kenton would roam the sprawling Hotel Casa del Mar in Santa Monica, the group’s headquarters in the late 1960s. “We ran through that place like cockroaches,” he said in a recent interview. In his early teens, he moved to the mountain compound in Badger, Calif. It was a happy childhood full of freedom, he insisted, with a sprawling non-biological family.

He called it “probably the single greatest community to grow up in.”

He was an enthusiastic participant in the Game. “It’s like catharsis — sharing and getting rid of anger. It was a great sort of lubricant for a community. It enabled all of us to air and share gripes and move forward. Here in society, you walk along with prejudice. In Synanon, there was none.”

In the late 1970s, Dederich’s push for mass vasectomies drove many members away. Many others submitted. Kenton had just turned 18 when he agreed to the procedure. He said it made philosophical sense to him.

“The idea was, why not be a parent to someone who needs a parent instead of having your own child? That increases the population of people who need parents.”

When Dederich launched a private security force called the Imperial Marines, Kenton was picked for the three-month training. A prosecutor would describe it as “a combat-ready paramilitary unit, trained in martial arts, weapons, high-speed automobile chases and the like.”

The rationale for its existence, Kenton said, was that “we were being harmed and attacked by outsiders all the time.” He loved Synanon and believed in its mission. He was good with snakes.

The crime was ham-fisted and swiftly solved. An alert neighbor had seen two men approach Morantz’s house and put something hastily in his mail slot before driving away in a green sedan.

The neighbor made note of the plate number, and police traced it to the Synanon compound in Badger, where the checkout logs proved incriminating. The odometer showed the car had traveled 1,000 miles the week of the attack — the distance of a round trip to and from the lawyer’s block in Pacific Palisades.

Seizing 13 audiotapes from the compound, police found hours of Dederich ranting menacingly in his distinctive bombastic growl.

Our main religious posture is this: Don’t mess with us. You can get killed dead. Physically dead. …

I’m quite willing to break some lawyer’s legs and then tell him next time, “I’m going to break your wife’s legs, and then we’re going to cut your kid’s arm off.” Try me. This is only a sample, you son of a bitch. And that’s the end of your lawyer. …

I want to crack some bones. …

The press got the tapes and played them endlessly. A Synanon lawyer explained that Dederich didn’t really mean it. He was just “a sick old man” who talked like a dockhand and indulged in hyperbole.

The recovering alcoholic who boasted of rescuing thousands of addicts, who called himself “the person who set all the standards for the care and feeding of delinquents,” who said his ideas would “save the goddamn world,” was now being charged with conspiracy to commit murder. When police came for him, Dederich was too drunk to walk.

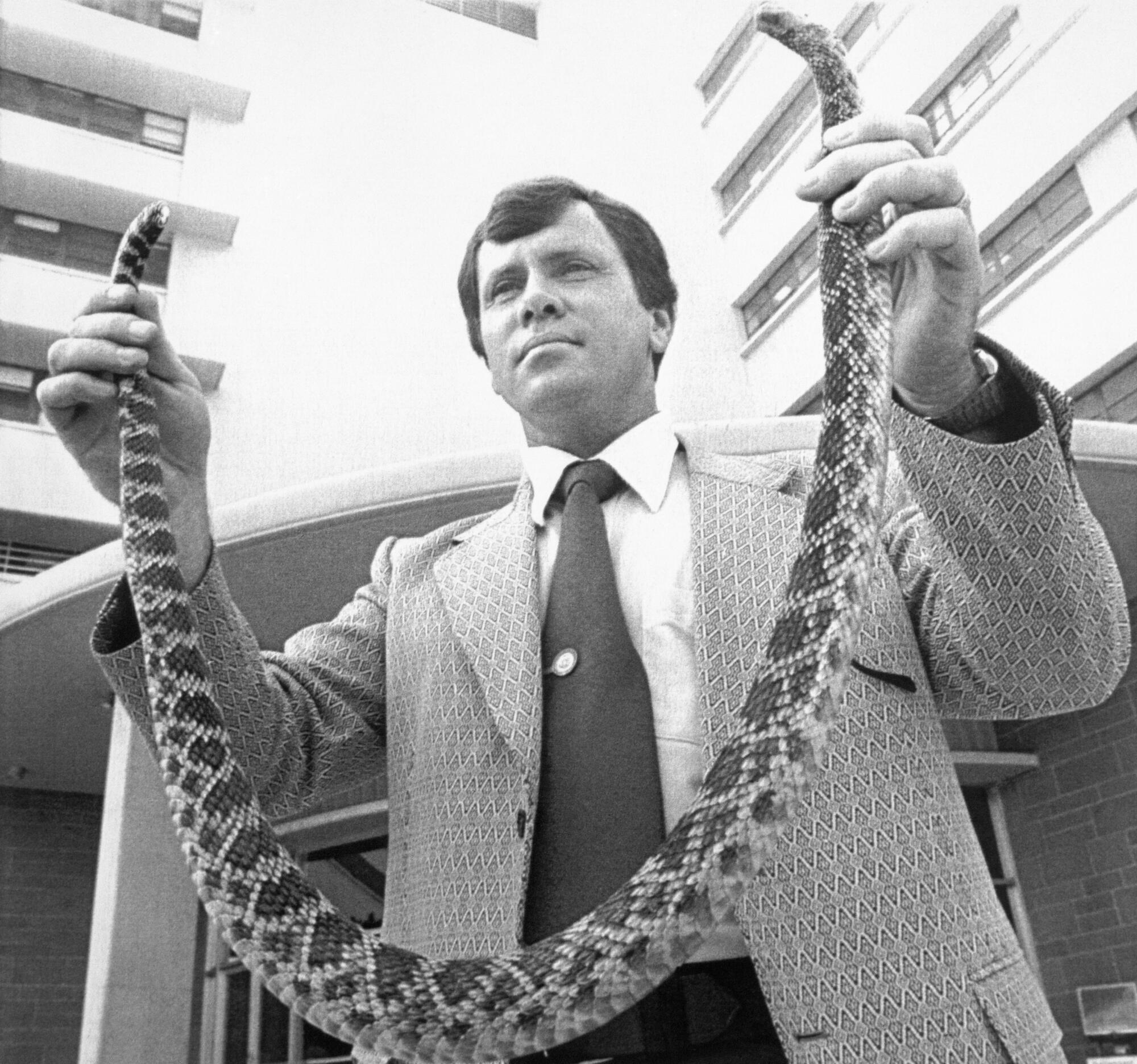

Two of his Imperial Marines were arrested on suspicion of executing the attack. One was Joseph Musico, 28, a struggling heroin addict and combat veteran who, people said, liked to boast that he wore a necklace of human ears in Vietnam. He had a hard scowl and cold eyes.

The other was Lance Kenton, 20, lean and fair-haired, his posture as straight as a soldier’s. Police had lifted his fingerprint from the window of the green sedan.

At the preliminary hearing, a defense attorney said Morantz had done it to himself. He’d put the snake in the mailbox, Paul Geragos suggested, because he “was seeking some kind of revenge” against a postal worker with whom he’d had a dispute.

Or maybe he had staged the attack on himself “as a means of drawing attention to his cause against Synanon and other groups.”

In July 1980, however, the three defendants pleaded no contest to charges connected to the attack. Dederich was spared jail time but barred from a leadership position in the group he had founded; his Imperial Marines each got a year in jail.

Morantz told reporters he had not advocated long sentences for men he considered victims of Dederich’s manipulation.

“I can’t find it in my heart to feel that Kenton and Musico should spend their lives in prison,” he said.

Late the following year, representing clients who were suing Synanon, Morantz walked into a hotel conference room in Visalia, Calif., to finally take a deposition from Dederich, whom he called “my bête noir … the man who sent two men and a snake to kill me.”

Dederich hobbled in on a cane with his lawyers. He said his memory had been wrecked by a series of strokes. Morantz felt “a powerful, creepy bond” with Dederich. “I wanted to take the measure of this man who had been my obsession for so long,” he wrote in his memoir, “Escape: My Lifelong War Against Cults.”

By Morantz’s account, Dederich admitted he was a salesman whose job was to pressure people to “do things they did not want to do.” Morantz probed for answers. He wanted to understand the dynamics of the group’s paranoia and what role Dederich had played in stoking it. Had Dederich pitched the idea that Synanon needed protection from hostile forces?

“I probably did,” Dederich said. “It’s a device that as a father and a grandfather I’ve used — the boogeyman will get you if you don’t watch out.”

Morantz called the rattlesnake attack “Synanon’s Pearl Harbor,” the event that summoned the force of the law and exposed what he called “a cesspool ruled by violence and one man’s madness.”

But what destroyed Synanon was the Internal Revenue Service, which revoked its tax-exempt status and stuck it with a massive bill for back taxes and penalties. It dissolved in 1991. Its founder survived six more years.

The snake attack made Morantz’s name, but it cost him heavily. The woman he had been in love with, frightened by Dederich’s rants, left him and eventually married another man. The pain in his hand never really went away. There was bone cancer, chemo and red blood cell aplasia that left him needing regular transfusions. He suspected his ailments might somehow be linked to the slow, insidious work of the venom.

Elijah Bowles picked up a package at the Twentynine Palms Post Office and found a live rattlesnake inside. An investigation is underway.

He met another woman and had a son, Chaz, who said that former Synanon members regarded his father as a hero and a friend.

“He was always kind of looking for a righteous battle to fight on behalf of people being taking advantage of by the Chuck Dederichs of the world,” Chaz told The Times. “He was enjoying his reputation as a very niche lawyer who specialized in cults and megalomaniacs.”

Morantz urged his son, only half-jokingly, not to pursue the “danger and drama” of a lawyer’s life. Taking inspiration from his father’s favorite film, “Apollo 13,” Chaz eventually joined the big team of engineers that put the rover Curiosity on Mars — though it was easy, listening to Morantz boast, to think his son had done it single-handedly.

Morantz, who died in 2022, considered Synanon his crucible.

“Like the reluctant hero of a Hitchcock spy thriller, I had to rise to the occasion, marshal resources I never knew I had and save the day,” he wrote in his memoir, which has a rattler on the cover.

While the tiny Point Reyes Light newspaper won a Pulitzer for its coverage of Synanon, Narda Zacchino of the Los Angeles Times was one of the few big-city reporters writing critically about the group before the snake attack. She became friends with Morantz, who told her that police had found a second rattlesnake in the canyon behind his house.

He thought that it had been intended for another victim, and that the attackers must have changed their minds and released it. “He said, ‘It was probably for you,’” she said in a recent interview.

Zacchino was featured in a recent HBO docuseries called “The Synanon Fix.” At the premiere party, she spotted Lance Kenton, who also appeared on the show. She introduced herself and asked him the questions that had gnawed at her for years: Was there a second snake? Was she on a hit list?

“He froze when I asked about the second snake,” she recalled. “He said, ‘There was no second snake.’”

Kenton, now 66, told The Times that he remembers the conversation. He insisted that Synanon did not have a hit list, only what he called a “s— list” — people who meant the group harm. Asked about the snake attack to which he pleaded no contest, he does not deny a part in it, but won’t talk about it either.

“I don’t really want to discuss it much,” he said. “I took responsibility, and that’s it — there’s no reason to discuss it. It’s 50 years ago.”

If you have information on old crimes, famous, once-famous or obscure, contact [email protected]

Still, his disdain for Morantz has endured across that half-century. He speaks of him as a man who didn’t understand Synanon and “didn’t really talk to anyone who wasn’t disgruntled.”

Kenton now manages properties in Malibu. Why did he take the plea? Facing life in prison, he said, “there was just no way out of it” otherwise.

“Who the hell wants to go to trial?” he said. “A criminal indictment is like cancer. You go to the doctor. They say you have cancer. When you adjudicate it, you say, ‘Oh, we’re gonna give you chemotherapy for three months.’ Fine.”

As part of his probation, Kenton was ordered not to associate with Synanon members, which in effect severed him from his entire social circle. There were other costs. “I always wanted to be a stockbroker, and I couldn’t do that because you can’t get bondable with a felony.”

Of the violence associated with Synanon, Kenton doesn’t blame the founder. “I think that probably some people were proactive and decided to do things that he didn’t necessarily know about.”

He mourns the demise of the group he calls “a beautiful place, a great community,” adding: “I think it helped a lot of people over the years. It’s a shame that it ended the way it did.”

Did the rattlesnake case lead to its collapse? “I don’t know if I’d want to accept that responsibility,” he replied.

In his late 60s, on a show called “Legally Speaking,” Morantz ruminated about his battle with Synanon and all it had cost him. It had scared away the woman he planned to marry. And though it was impossible to prove, he suspected the lightning flash of the fangs had been killing him at a glacial pace for decades.

But fate had uncoiled in surprising ways. If he hadn’t put his hand in the mail chute, his fiancee might have stayed. And he would not have married the woman who gave him a son who helped steer a wheeled robot across the surface of the Red Planet.

Knowing that his son’s existence hinged on it, he said, he would not have done anything differently.

“I would have stuck my hand in the mailbox.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.