Will these drones ‘revolutionize’ 911 response? L.A. suburb will be first to test

A black-and-white drone about the size of a sofa cushion took off with a gentle whir at the Hawthorne Police Department earlier this month, hovering and darting back and forth a few times before landing on a podium to a round of applause.

A small audience and local TV news crews had gathered to see the unveiling of “Responder,” marketed as the first drone built specifically to respond to 911 calls by quickly arriving at scenes, beaming a live video feed and, if necessary, dropping off medical supplies.

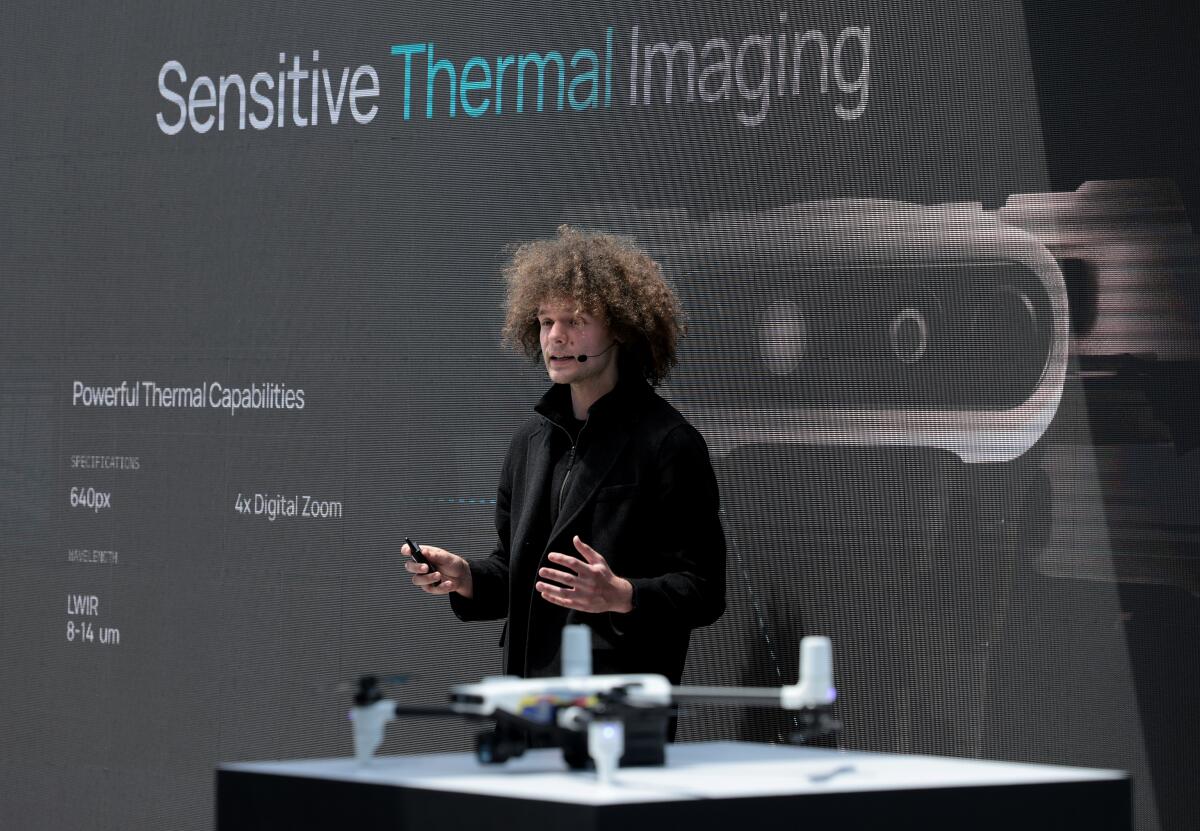

The company behind the new drone, Seattle-based Brinc — a tech startup with a 24-year-old chief executive — has boasted it will “revolutionize the public safety landscape.” But law enforcement agencies across Southern California and the country already employ drones for a variety of purposes, including 911 response, and skeptics warn about the risk of “mission creep” when the technology is weaponized or used for surveillance.

Some Los Angeles activists have fought to limit police drone use, but Hawthorne’s adoption of Brinc’s Responder is a sign some local authorities are continuing to embrace unmanned aerial vehicles despite the pushback and price tag.

A contract with Brinc starts in the low tens of thousands and can run into the millions of dollars, a spokesperson for the company said. The exact price depends on what the drones are used for and the number of launch sites, among other factors.

Hawthorne will be the first agency to test out the dedicated 911 drones, with plans to have a small fleet airborne by the end of this year. They will be stationed at charging “nests” throughout the city, ready to be deployed to a nearby emergency, Brinc said in a news release, which listed OpenAI CEO Sam Altman as one of the company’s investors.

Many of the features touted in Responder overlap with the commercial drones currently used by law enforcement. One distinct difference is the aesthetic, with Brinc adding red and blue lights and a siren to its craft.

The Santa Monica Police Department began using drones to respond to 911 calls in November 2021, said Sgt. Derek Leone, who oversees the department’s drone program. It gets its drones from the major manufacturer DJI, a Chinese-owned company. Brinc emphasizes that its drones are American-made.

“Brinc is definitely trying to make itself stand out by having purposely built for a lot of the needs that law enforcement has,” Leone said. “It is an attempt to specifically tailor the drone towards our mission, but we operate very capably with what we have.”

The Los Angeles Police Department first considered adding drones to its arsenal in 2014 when it received two from authorities in Seattle, where the community had rejected them over privacy concerns.

The ACLU of Southern California raised its own objections at the time, arguing that drones “can be used for completely surreptitious surveillance that a helicopter could never perform — and could pose particular threats to privacy when combined with other technology like facial recognition software, infrared night vision cameras, or microphones to record personal conversations.”

The LAPD adopted regulations in 2019 that said drones cannot be equipped with weapons or facial recognition software.

Police say drones are useful to monitor hostage situations or get a clear view of a barricaded suspect. Drones can also help search for fugitives or missing persons, and they can also provide thermal readings for firefighters.

At the Brinc presentation in Hawthorne, company founder and CEO Blake Resnick played a video with a hypothetical example of a drone in action. A convenience store owner is shown dialing 911 to report a potential robbery after he sees a man with a gun near the store. A drone arrives, and its camera captures footage showing the suspected weapon is actually a lighter shaped like a firearm, preventing a false alarm.

The Chula Vista Police Department in San Diego County was the first to use drones to respond to 911 calls in 2018 as part of a Federal Aviation Administration pilot program.

Officials stationed drones atop the police station roof and deployed them to 911 call locations when appropriate.

For the record:

9:35 a.m. May 24, 2024An earlier version of this article identified Don Redmond as a retired Chula Vista police chief. He retired as a police captain.

According to Don Redmond, a retired Chula Vista police captain, the department’s drones were getting to emergency scenes in roughly half the time as police officers and also capturing recordings of crimes in progress.

Chula Vista found that sending a drone to a 911 call enabled officials to avoid dispatching an officer 25% of the time, according to Redmond, who now works for Brinc as the company’s vice president of advanced public safety projects.

“Across the country, everybody’s struggling for staffing purposes,” Redmond said. “Here’s an innovative way to keep police officers on priority calls.”

Police departments in Beverly Hills and Irvine also use drones to respond to 911 calls.

“The drone can get to a call much faster than an officer can even in the best of circumstances and sometimes even clear the call,” Santa Monica Police Lt. Erika Aklufi said.

Stop LAPD Spying Coalition organizer Hamid Khan said his group fought to keep LAPD drones grounded between 2014 and 2017, and there’s still “quite a bit of concern” over their continued use.

“They have the capacity to surveil, to gather data and to constantly monitor,” Khan said.

Although drones may be intended only for specific circumstances such as 911 calls, Khan is worried they will become more ubiquitous as time goes on, with “mission creep” eventually leading to more dangerous applications.

The majority of police drones are not weaponized, and Brinc says it will never enable its devices to use deadly force, but Khan pointed to North Dakota, which became the first state to legalize armed police drones in 2015.

“They are claiming that they will never be armed, but we see how policies can change,” Khan said.

Some local officials shrugged at Brinc’s arrival in Hawthorne and the renewed debate it has sparked.

Former LAPD SWAT officer John Incontro said drones have long been a powerful tool for law enforcement.

“They get there first on scene and they’re able to orbit and see what’s going on,” said Incontro, now police chief in San Marino. “It’s kind of like having a helicopter available.”

After hearing about Responder, Incontro wondered what features set it apart from the drones his department recently received and is preparing to use to scope out reports of suspicious activity at large estates in the area.

“I wasn’t familiar with a company that’s making drones specifically to respond to 911 calls,” he said. “I don’t know why that’d be more special than what I just described.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.