L.A. County to offer discounted home internet to lower-income residents in some neighborhoods

With the federal government poised to slash subsidies for internet service, L.A. County has started work on a wireless broadband network that will deliver high-speed connections for as little as $25 a month.

The county announced this week that it had signed a contract with WeLink of Lehi, Utah, to build the network and offer the service in East Los Angeles, Boyle Heights and South Los Angeles. Qualified households will be offered a $40-per-month discount on WeLink’s rates, meaning they could obtain the basic 500-megabits-per-second service for $25 a month.

The contract brings a new internet provider to neighborhoods now served mainly by Spectrum and AT&T, which also offer discounted service for lower-income residents — though at much lower speeds. But it will take months for WeLink to build its network, which will rely on a series of rooftop antennas connected to the internet through existing fiber-optic lines.

The looming loss of federal subsidies is a much more immediate problem. Unless Congress renews its funding, the Affordable Connectivity Program will be lapsing this month, terminating a $30-per-month benefit that has allowed 23 million lower-income households to obtain broadband service at little or no cost.

The Affordable Connectivity Program, which offers a $30 subsidy, helping millions of households across the U.S. connect to the internet, is slated to expire.

L.A. County has more of these subsidy recipients than any other county in the country — 983,000 households, said Eric Sasaki, manager of major programs for the county’s Internal Services Department. The county’s enrollment, he said, is higher than that in 45 states.

The county’s deal with WeLink has similar roots to the Affordable Connectivity Program, which grew out of the emergency broadband subsidy program the federal government launched at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

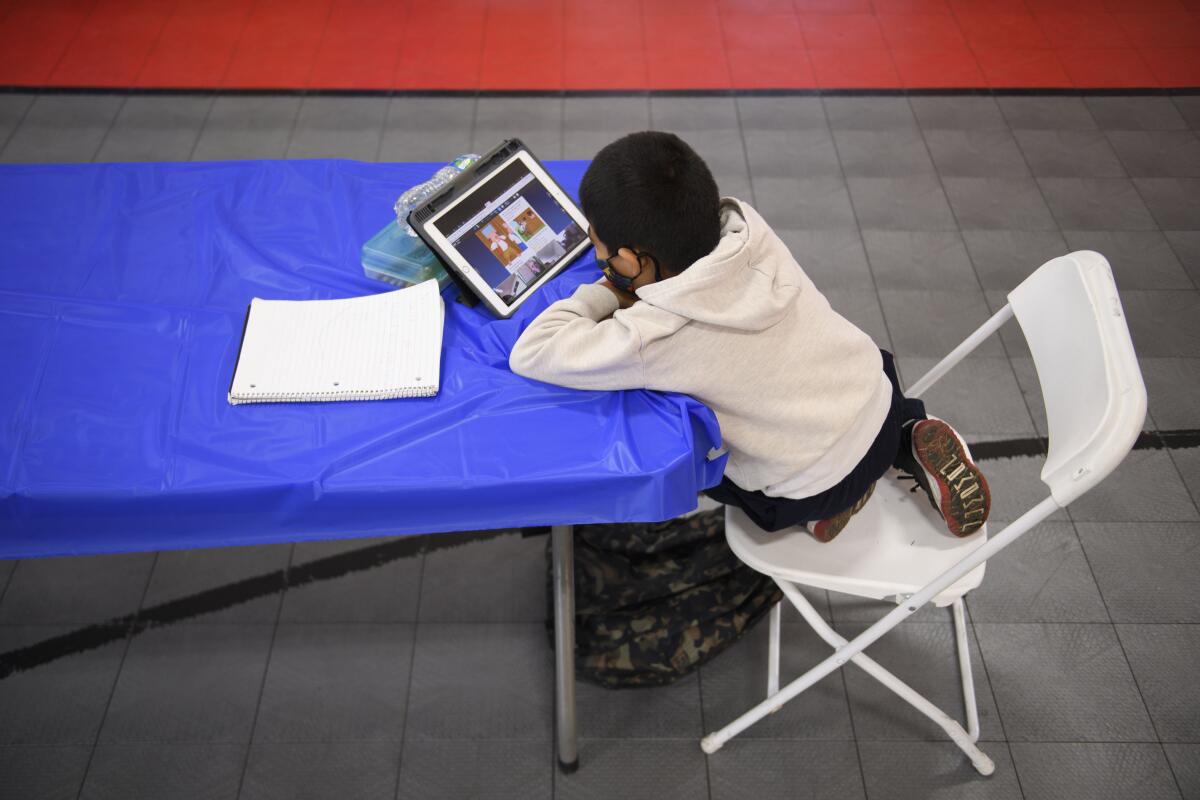

In 2021, Sasaki said, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors decided to explore ways to bring high-speed internet quickly to lower-income neighborhoods where more than 20% of the homes weren’t connected. Concerned about kids struggling to attend online classes, the county looked at putting wireless internet hubs at libraries, parks and even restaurant chains before deciding to conduct demonstration projects in four regions: East L.A./Boyle Heights, South L.A., the northern part of the San Fernando Valley, and five cities in the southeastern part of the county.

The county has received $50 million in federal funds for the projects, but about $45 million will go to the East L.A. and South L.A. rollouts, Sasaki said.

“We are also looking for additional funding sources to help execute additional projects,” he said.

Low-income residents often paid more for worse service than their neighbors in higher-income areas, according to a new report.

The demonstration projects “are kind of a proof of what is possible,” Sasaki said. “The idea was that these would be sustainable and long term.”

WeLink’s service area in East L.A. and South L.A. covers more than 275,000 households and small businesses within 68 square miles.

All or part of the following communities are to be served:

East Los Angeles, Boyle Heights, Lincoln Heights, Montecito Heights, El Sereno, Adams-Normandie, University Park, Historic South-Central, Exposition Park, Vermont Square, South Park, Central-Alameda, Chesterfield Square, Harvard Park, Vermont-Slauson, Florence, Florence-Firestone, Manchester Square, Vermont Knolls, Gramercy Park, Westmont, Vermont Vista, Broadway-Manchester, Green Meadows, Watts, Athens, Willowbrook, West Rancho Dominguez and Walnut Park.

Low-income L.A. families are struggling to get students connected to the internet even with promises of help from phone and cable providers. A survey found 16% still unconnected.

The company plans four tiers of service, with equal speeds for uploads and downloads: $65 a month for 500 Mbps, $75 for 1 gigabyte per second, $85 for 2 Gbps, and $99 for small-business connections. Installation and a router will be included, WeLink Chief Executive Luke Langford said.

Qualified homes will receive a $40-a-month discount on the residential tiers. The initial plan is to use the same eligibility requirement the federal government uses for the Affordable Connectivity Program: households earning up to 200% of the federal poverty level, which would be $30,120 for a single individual or $62,400 for a family of four. If the federal program is extended, qualified households would be able to receive the WeLink service at no cost.

If the program is not extended, WeLink and the county will come up with an alternative metric, Langford said, adding that his company is comfortable offering the discounts under the current terms.

The contract calls for WeLink to provide discounted service to 50,000 households. Sasaki said the county would be thrilled if that many homes signed up for the $25 monthly service; if there is even more demand, he said, the county will look for ways to support it.

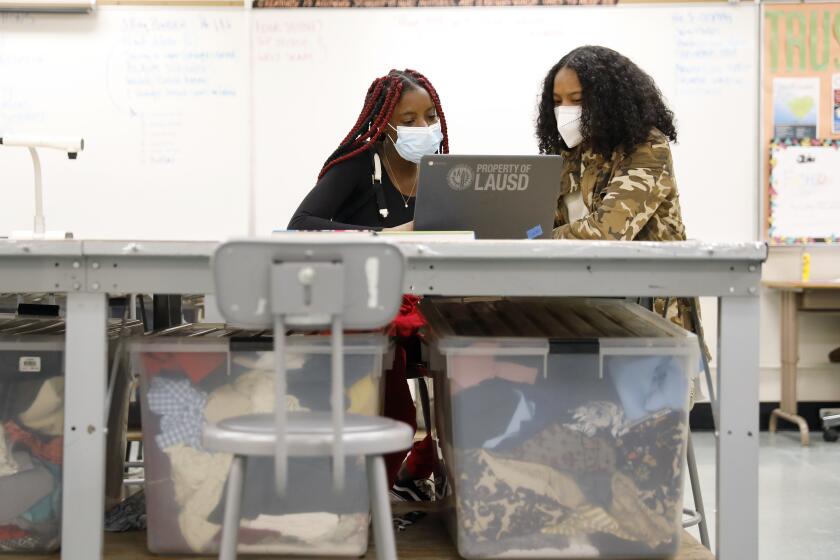

Low-income families remain poorly connected online for schoolwork. L.A. Unified tries once more to help, at least for a year.

Surveys show that lower-income households are less likely to have a home internet connection not because the service isn’t available, but mainly because it’s not affordable. Other problems include not having a computer or knowing how to use one, as well as a lack of awareness about programs that can help users overcome these hurdles.

Sasaki said the county plans to address those issues with programs to supply free laptops and technical assistance from “digital navigators” in the communities being served.

It wasn’t an explicit goal of the community broadband program to spark more competition among internet providers, but that’s happening with the WeLink deployment. And if Spectrum and AT&T lower their prices in response, Sasaki and Langford said, that’s another way the project will benefit targeted communities.

WeLink uses unlicensed spectrum in the 60-gigahertz band of frequencies, which means it doesn’t need to obtain permits for the airwaves or tear up streets for new fiber-optic lines. It will also design the network in a way that reduces the number of antennas required to carry data.

Those steps should speed construction of the network, Langford said. But WeLink still has to strike deals to mount its antennas on rooftops, lights and street poles, he said, as well as to use the fiber-optic lines that will connect its network to the internet.

The California Public Utilities Commission voted to fundamentally change how electricity is billed by adding a new monthly fixed fee.

Langford said he expects a “relatively modest” number of customers to be offered service by the end of the year, with the bulk of the deployment going live in 2025 and beyond. People interested in the service can sign up for updates at the WeLink website.

The very high frequencies used by WeLink can transmit an enormous amount of data, but unlike the lower frequencies used by radio stations and cellphones, they don’t travel well through walls. Langford said WeLink installers will either use new cables or a building’s existing wiring to connect the rooftop antennas to routers inside customers’ homes and businesses.

Founded in 2018, WeLink has built networks serving parts of Las Vegas, Phoenix, Dallas, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles, Langford said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.