California DOJ civil rights probe of Sheriff’s Department headed to settlement, sources say

More than three years after the California Department of Justice launched a civil rights investigation into the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, the case is headed toward a sprawling settlement agreement expected to touch on issues including jail conditions, deputy gangs and staffing, according to sources familiar with the matter and emails viewed by The Times.

The investigative findings — which remain secret — span over 100 pages, and sources say they include controversial recommendations for deputies to curtail making traffic stops, stop enforcing some drug laws and complete hundreds more hours of training.

Initially launched in January 2021 under Xavier Becerra, California’s attorney general at the time, the probe came amid a string of controversial shootings, costly lawsuits, repeated allegations of deputy misconduct and then-Sheriff Alex Villanueva’s resistance to oversight.

Though a new administration is in place, many of the same problems remain — some of which the state detailed when presenting the findings of its investigation to department officials and other stakeholders in a recent meeting, according to four sources who asked to remain anonymous because they were not authorized to speak on the record.

Already, the findings and recommendations have sparked pushback, some from oversight officials who raised concerns about the lack of transparency and some from union leaders who questioned the practicality of the state’s nearly 400 recommendations.

“Preventing deputies from conducting traffic stops and enforcing drug laws might seem like a good idea to those living in gated communities or with armed protective details,” Richard Pippin, president of the Assn. of Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs, wrote in a recent message to union members. “But ALADS knows our community partners in the contract cities and elsewhere will be shocked by some of these proposals that are best described as elitist and unrealistic.”

The Sheriff’s Department said this week it was “not at liberty” to discuss the matter, while Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s office did not respond to The Times’ request for comment. Lawyers for Los Angeles County said only that they’d been in communication with the state and “hoped to avoid litigation.”

California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra’s office says it will look at whether the department has engaged in a pattern of unconstitutional policing.

The Sheriff’s Department is already subject to five more narrowly targeted settlement agreements overseen by federal courts. One centers on racial profiling and policing practices in the Antelope Valley, while the other four relate to the conditions and treatment of inmates in the county jails. The oldest of those cases dates to the 1970s, but it remains open because the department has never fully complied with the settlement terms.

Given the scope of the state’s investigation, a new settlement agreement could be far broader than those already in place. And given the sheer size of the Sheriff’s Department — the largest in the country, with a $4-billion budget — it could be one of the most expansive that the California Department of Justice has ever entered.

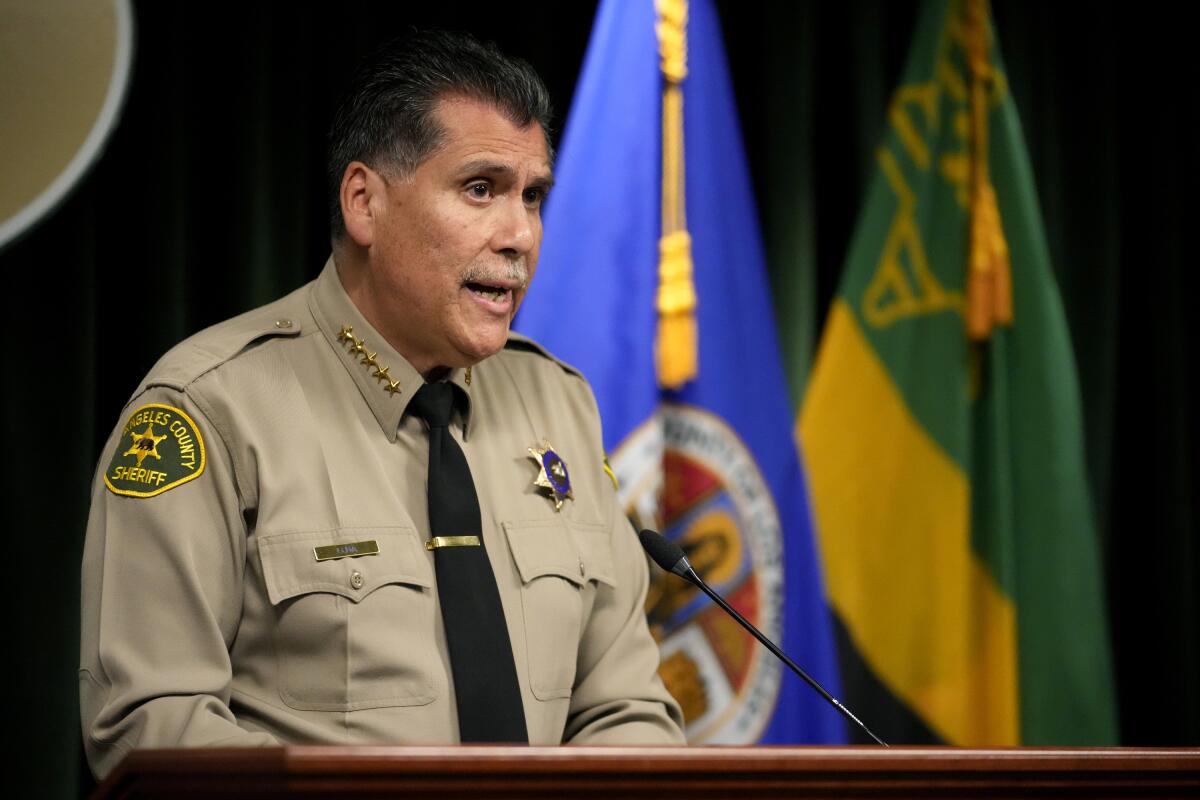

Word of the state’s voluminous findings began making the rounds last week, after Sheriff Robert Luna sent a lengthy email to deputies offering a vague update on the status of the case.

“As some of you may know, three years ago in January 2021, the California Department of Justice (CAL-DOJ) began a civil rights investigation into the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department to determine whether the LASD has engaged in a pattern or practice of unconstitutional policing,” the email began, according to a copy reviewed by The Times.

“We have been communicating with the CAL-DOJ officials and look forward to addressing the issues of concern and coming into compliance,” the sheriff continued. “We expect further communication with CAL-DOJ in the weeks and months ahead regarding proposed corrective actions.”

The email did not offer a clear timeline for the next steps, but Luna wrote that the department, county lawyers and “other key stakeholders” would need to evaluate the findings and recommendations, which he said would touch on more than a dozen areas, including use of force, arrests, deputy gangs, internal investigations, discipline, oversight, community engagement, training, staffing and conditions in the jails.

Any agreement reached between CAL-DOJ and the Sheriff’s Department will help make sure the department complies with state laws and standards and could improve trust from the community, he said.

“As we work towards finalizing the specifics, we will keep you informed of any developments or changes,” Luna wrote. “Community trust is at the core of our work in public safety and with this agreement we will improve our systems and Department to better serve the citizens of Los Angeles County.”

California law allows the attorney general to investigate law enforcement agencies suspected of engaging in a “pattern or practice” of violating state or federal law. Unlike with criminal investigations that focus on specific incidents, a pattern or practice investigation looks more broadly at whether a law enforcement agency routinely violates people’s constitutional rights.

When he first announced the Los Angeles County investigation, Becerra raised concerns about the lack of comprehensive oversight of the department as well as allegations of retaliation, excessive force and other misconduct.

“There are serious concerns and reports that accountability and adherence to legitimate policing practices have lapsed at the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department,” he said in a statement. “We are undertaking this investigation to determine if LASD has violated the law or the rights of the people of Los Angeles County.”

At the time, Becerra did not specify a focus for the investigation, saying that his office was “not placing a particular scope and time or place, or person” in the crosshairs.

Though Becerra initially said a thorough report on the investigation’s findings would be made public, it is not clear whether Bonta still plans to do that. One county source familiar with the matter said it was likely the detailed findings would remain secret, though a signed settlement agreement would eventually become public.

The original announcement of the investigation three years ago came after a series of high-profile shootings by deputies that triggered widespread protests and demands from community organizers and lawmakers for independent investigations. Those calls were amplified after the June 2020 killing of 18-year-old Andres Guardado, who was shot five times in the back by a deputy assigned to the Compton station.

Last year — a few months before both that deputy and his partner were sentenced to federal prison for an unrelated incident — The Times obtained a leaked email showing that the California Department of Justice had taken up the Guardado case. It’s not clear if that became part of the civil rights probe or if it is being handled separately, though the California Constitution grants the office the power to review cases where the “law is not being adequately enforced” by a local or county agency.

Christopher Hernandez received an 18-month sentence for conspiring to violate the civil rights of a 23-year-old man who yelled at him and his ex-partner to stop picking on a group of teens at a park.

When Becerra opened the broader civil rights probe in 2021, local activists and oversight officials heralded the move. Melina Abdullah, co-founder of Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles, called it “a step forward in the names of people like Dijon Kizzee and Andres Guardado and so many others” killed by L.A. deputies, adding that she hoped it would uncover corruption in the department and bring an end to deputy gangs.

Robert Bonner, a former federal judge who now serves on the watchdog Civilian Oversight Commission, said at the time that he hoped the investigation would focus on deputy cliques and would eventually lead to a consent decree requiring their elimination.

Though Villanueva didn’t learn of the probe until it was announced publicly, he said in 2021 that he welcomed the attorney general’s investigation and promised to cooperate.

“Our department may finally have an impartial, objective assessment of our operations, and recommendations on any areas we can improve our service to the community,” he said. “We are eager to get this process started, in the interest of transparency and accountability.”

This week in an email to The Times, Villanueva — who lost a reelection bid two years ago — took a dimmer view of the state’s investigation.

“The entire premise of their investigation was political retaliation by the Board of Supervisors and their political appointees,” he wrote, accusing supervisors of lobbying the attorney general to open the case. “With federal consent decrees covering most of LASD operations already, there is little room for state intervention.”

Union officials also worried about the burden of adding new requirements from another sprawling settlement.

“The report clearly indicates that every deputy would be required to complete hundreds of hours of training to satisfy even the baseline requirements,” Pippin wrote in his message to union members. “The report also challenges the direct authority of the sworn chain of command and moves much of the power and decision-making authority to offices or groups with zero operational experience,” he continued, saying the state’s recommendations would “create confusion in the chain of command.”

Meanwhile some oversight officials worried about the apparent lack of outside input.

“I just hope the attorney general and the county officials will take input from the community before reaching a final settlement,” said Sean Kennedy, who chairs the Civilian Oversight Commission. “No real solution can be forged without hearing from the people most affected by decades of unconstitutional policing.”

At the outset, it was expected that the inquiry would involve interviews with local officials, members of oversight panels and community groups — though it’s not clear who has been interviewed or what the investigation ultimately entailed. Kennedy said the oversight commission has not been included in “any of the settlement meetings to date.”

A similar investigation of the Kern County Sheriff’s Office that started in 2016 led to a settlement agreement four years later, when the agency agreed to implement a laundry list of reforms that included a ban on the use of chokeholds, a new procedure for reporting deputy shootings to the public and stricter rules governing deputy searches.

Nearly a decade earlier a two-year probe overseen by then-Atty. Gen. Jerry Brown found that Maywood, a small city in southeastern Los Angeles County, was patrolled by “rogue cops” who arrested people without probable cause and routinely used excessive force.

The Maywood Police Department reached an agreement with the state that required the city to raise its hiring standards, publish annual audits of the department’s operations, and equip officers with audio recorders and their cruisers with video cameras, among other reforms. A year after entering the agreement, Maywood disbanded its police force and instead contracted with the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.