After killing his nephews, he fled the L.A. area for China. Was it revenge or a psychotic break?

Deyun Shi sat with his hands clasped and his eyes downcast, his face impassive behind black-framed glasses as a screen in the Alhambra Courthouse flashed one image after another of his two teenage nephews, bloody and tangled in their bedsheets.

Anthony Lin, 15, was sleeping when he was bludgeoned to death with a two-foot long pair of bolt cutters on Jan. 22, 2016, prosecutors say. His older brother William, 16, was wide awake, and appears to have fought their attacker. He was found bloodied under a blanket on the floor, his skull split open, the lead pipe used to beat him left beside an American history textbook on the bed at their home in Arcadia.

Jurors choked back tears and stifled gasps as Deputy Dist. Atty. MacKenzie Teymouri described the crime scene — and the evidence that the prosecutor said indicated the boys’ uncle was the killer.

“Detectives found the bloody bolt cutters wrapped in a towel in [Shi’s] car, with DNA from both Anthony and William on it,” the prosecutor said. “He got a parking ticket while he was inside killing the children.”

The facts of the actions are not in dispute. Nor is the identity of the perpetrator, who has spent much of the intervening years being assessed for competency to stand trial and recovering from a heart attack and subsequent stroke he suffered in pretrial detention.

Instead, the case will hinge on whether jurors believe the killings were the culmination of a “calculated plan of rage and revenge,” as prosecutors allege, or whether Shi was in the throes of a psychotic break, as the defense contends.

For adolescents, suicide prevention often starts with other teens. That’s what drew Donald “Trey” Brown III to Teen Line, where he was training before his suicide.

Shi, 52, glanced occasionally toward the Mandarin interpreters in the gallery as Teymouri laid out the details of the bloody assault Thursday morning — seven years, one month and six days after he was detained by authorities in Hong Kong, where he fled in the hours after the attacks.

Shi is charged with two counts of first-degree murder and felony domestic violence in connection with William‘s and Anthony’s deaths and an attack on his then-wife, Yujin “Amy” Lin, who was bludgeoned with a metal wood-splitting tool while next to their 8-year-old son.

That assault ended when Shi’s teenage son wrestled his father away. Shi’s in-laws, David and Vicki Lin, rushed to the hospital to tend to Amy, and were still there when their children were slain.

Shi’s lawyers say he was suffering from schizoaffective disorder and post traumatic stress disorder when he first learned his wife had filed for divorce on Jan 21, 2016.

They say he was not in his right mind when he left the Pasadena Courthouse where officials were arguing the terms of his mother-in-law’s restraining order against him. They say the wealthy businessman was delusional when he went to the East West Bank and initiated nine wire transfers of $49,000 each — just under the legal limit for individual transactions — to people in his hometown in China, each using his sister’s phone number.

“This is not about whether our client committed those acts — he did,” defense attorney Vicki Podberesky told jurors Thursday. “This case is about mental health.”

Podberesky argued her client was psychotic when he drove to Los Angeles International Airport just after the killings on Jan. 22, his bag stuffed with six kinds of foreign currency and legal ID from three sovereign nations, and calmly negotiated for a seat upgrade from Cathay Pacific Airlines, paying in cash for a one-way ticket to Hong Kong.

“Mr. Shi was acting under an active mental illness,” the attorney said. “He did not have the requisite state of mind to have committed the murders as charged in this case.”

Samuel Bond Haskell IV, 35, was arrested in November on suspicion of killing his wife and her parents after he allegedly hired day laborers to carry away bags full of human remains.

Shi’s defense team also pushed back on the prosecutors’ theory that killing his nephews could be an extension of his violence against his wife or rage at his brother-in-law, the boys’ father, who had helped her escape Shi’s escalating assaults. The defense argued his nephews fall outside the definitions of kinship set by California’s domestic violence laws.

But evidence presented in court and documented extensively in records reviewed by The Times show what domestic violence experts call a textbook pattern of coercive control — a pattern that often involves threats and attacks on children and extended family.

“It’s often easier and more satisfying to the abuser to harm the children and leave the victim alive to suffer,” said Gail Pincus, executive director of the Domestic Violence Abuse Center in Los Angeles, who is not involved in the case.

As part of her divorce case, Amy Lin described a long history of angry outbursts and repeated fits of violence.

When Shi was upset, she said, he would take her phone, keys, purse and credit cards, leaving her helpless to escape. He’d also threatened to drain the family’s bank accounts and take their children out of the country, she alleged.

Judge Jared Moses has limited what portion of previous allegations of abuse can be admitted as evidence. Lin said the violence began early in their marriage, while the couple still lived in China.

“He would punch me with his fist and kick me with his foot,” Lin said in court Thursday — the first time she had seen Shi since he broke into their La Cañada Flintridge home just before midnight on Jan 21, 2016, fracturing her nose and slashing her face.

Jerrid Joseph Powell, 33, was charged with four counts of murder. Prosecutors say he gunned down three homeless men and a robbery victim in a four-day span last week.

“Very often it would be because of the things that happened at work and sometimes I did not even know what made him angry,” Lin said.

Then, in late 2015, that violence began to escalate, Lin said.

In early December, barely two months before the killings, he forced Amy to kneel in front of him and strangled her until she couldn’t breathe, she told the court in custody filings. He also smothered her with a pillow until she fought him off, she testified Thursday.

Experts said prosecutors may struggle to convince jurors that violence could spread from the couple to their nephews.

“If you don’t draw the link for them they’re not going to see it,” Pincus said. “They’ll buy the defense’s story.”

Lin’s own testimony could further complicate the picture.

“Shi never told me, or made any threats to me, that he would attack my nephews,” she testified in a wrongful death suit brought by her brother and his wife, which was quoted in a pretrial filing by the defense. “I never told Shi that the reason for my divorce had anything to do with David, Vicki or their kids.”

But testimony and court records appeared to show Shi considered his brother-in-law an enemy.

“He would go through my messages and my emails. He’d see my messages with David,” and become enraged, Amy Lin testified Thursday. “David would tell me certain things about the U.S., like about calling the police” in response to domestic violence.

On Dec. 30, Shi drove to Lin’s mother’s house and tried to force his wife to leave with him, grabbing her when she refused, court records show.

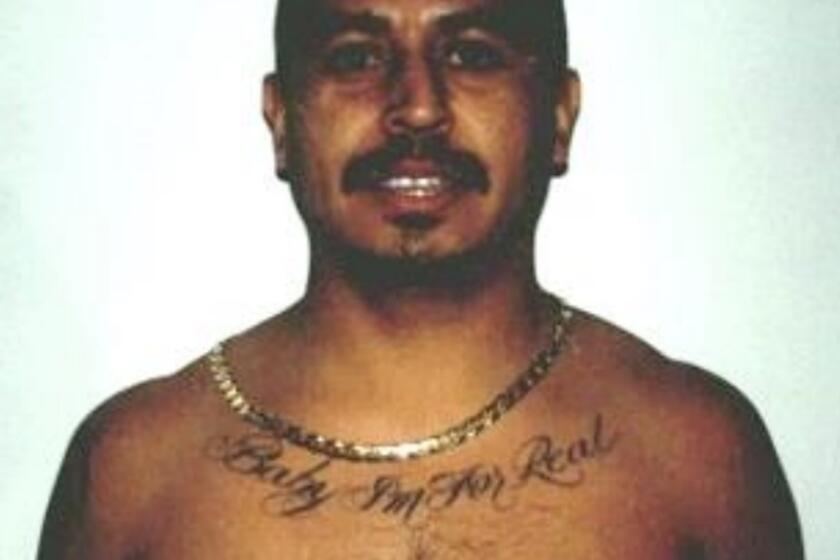

Los Angeles County prosecutors allege that Juan ‘Termite’ Romero set fire to a crowded apartment building, killing seven children and three women.

Her brother David stepped in to protect her, ending up on the pavement in a brawl with his brother-in-law, Lin testified. Lin’s mother tried to intervene and was thrown to the ground, she said.

David Lin called 911, but the family declined to press charges, Lin said.

“David said we could apply for a restraining order to prevent him from hurting us again,” she said. “I was very afraid he might hurt my two kids.”

The next day, aided by her brother, records show both Lin and her mother sought restraining orders against Shi.

“My mind is set,” Lin said in court filings. “I cannot continue to suffer threats by [Shi] and physical harm as he has been doing this for many years.”

Phone records show Shi spent the weeks he was under the restraining order Googling California divorce law, killers who escaped justice or got only light sentences, and Chinese extradition policies.

A week before the attacks, he went on the Chinese-language chat forum Zhihu and asked: “Can a Chinese citizen, who returns to China after committing a crime overseas (with the victims being a local citizen), avoid punishment?”

He had also voiced his growing anger to his older son, Zheyaun “Torres” Shi.

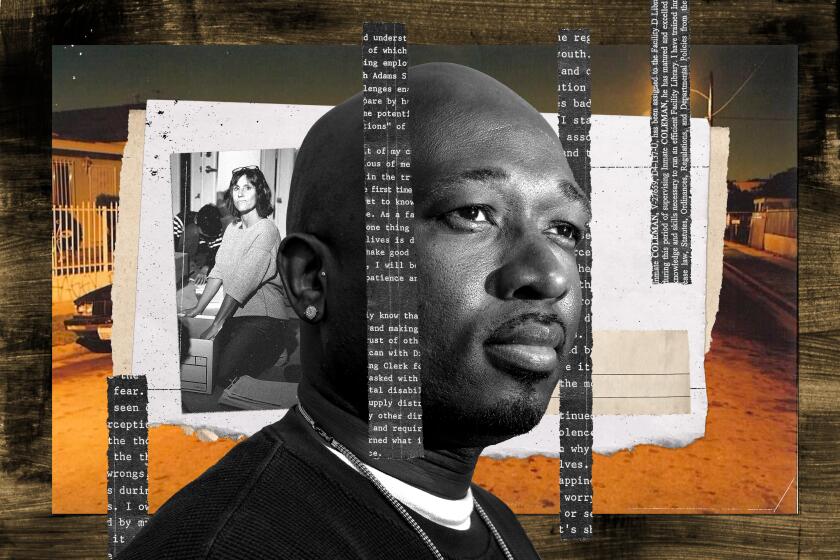

The two men were convicted of a murder they did not commit. But how could they prove their innocence from behind bars? How could they be exonerated without help?

Shi’s son testified that, on a trip to Disneyland with his children in January 2016, his father raged over the state’s community property laws, which typically require an equal split of marital assets.

“That’s why he did not want the divorce, he thought my mom was spending his money from all the hard work he did,” Shi’s 24-year-old son testified Thursday. “He believed David was behind my mother for this divorce so David could take some of the money from my mother after the divorce.”

“He said if he cannot get back with my mother, he would waste his money on a lawsuit rather than have my mother and my uncle take his money,” Torres Shi said.

Yet, even as he fumed over the financial implications of a legal split, Shi still didn’t appear to believe the divorce was imminent until he was told paperwork had been filed on Jan 21.

“This is when the plan began,” Teymouri, the prosecutor, said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.