Take a walk through L.A.’s spectacular, neglected and paved-over cemeteries

The poet Robert Frost was born in San Francisco, but by the time he wrote this verse, he had long since kicked its gold dust from his heels:

I met a Californian who would /

Talk California — a state so blessed /

He said, in climate, none had ever died there /

A natural death, and Vigilance Committees /

Had had to organize to stock the graveyards /

And vindicate the state’s humanity.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Yes, we have obliged the undertakers with mayhem deaths unnumbered. But we have also filled our cemeteries with those who defied the remedies of sunshine and citrus, and died abed anyway.

In the sylvan acreage of cemeteries like Forest Lawn, we now give death the space to be just one more extreme lifestyle choice, where the body — tanned and tended in life — is, in the words of the British novelist Evelyn Waugh, “more chic in death than ever before.”

For now, put aside the monuments to our celebrity dead and their tourism industry subset. Fans mark Marilyn Monroe’s crypt with lipsticky kisses, and are kept an enforced distance from Michael Jackson’s marble sepulcher in Glendale, at Forest Lawn.

This column is about the last-stop real estate for regular Angelenos. It’s sometimes an unnerving story of neglect, decay, financial fiddling, outright vandalism — of tombstones moved and muddled and lost — of bodies brutally exhumed by flood and mud or forgotten and paved over.

Poor Verdugo Hills Cemetery, above Tujunga, is a cautionary tale. In 1978, two years after the cemetery lost its license, a hillside deluge plunged bodies into streets and yards. Nearly 20 years later, vandals dug up and defiled corpses. Now, as at other historic cemeteries, volunteers labor admirably to keep the place in the trim.

In Long Beach, the picturesque 1906 Sunnyside Cemetery was this close to closing before the city voted five years ago to take it over. In 1994, the owner had embezzled more than $500,000 from the cemetery endowment fund and bought himself a Mercedes, which was not of much use in prison, where he was sent for the crime.

Elsewhere, graves were sometimes filled, emptied and re-sold. And plots and spots for people of color, if not barred outright, were pushed to the margins and neglected.

The Westside Pavilion is being remade as a UCLA biomedical research facility, an Orange County mall will become housing, and Gen Z seems to actually like shopping at malls.

Early this year, nearly 600 grave markers were stolen from Woodlawn Celestial Gardens in Compton. It’s one of many cemeteries, ancient for Los Angeles, that had slid by steps and missteps from its prime.

It opened not long after the Civil War, and it numbers among its residents not only veterans of that war but, so it’s said, veterans of the War of 1812. In latter days, the families of local Black Panther co-founder Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter and Negro Leagues pitcher Theolic Smith have buried their dead there.

Our oldest known graveyard is, of course, the La Brea tar pits. In 1914, part of a human skeleton was found entombed, a Native American woman who died a hundred centuries ago. She was in her late teens or early 20s. Her skull was fractured, either in an accident, or posthumously, or — most sensationally — in a crime, making her Los Angeles’ first known murder victim.

Land in and around Cal State Long Beach is the sacred ancestral home of the Tongvas’ divine founder and lawgiver, Chingishish, and ancient human remains have been discovered there over the years, occasioning ceremonial reburials.

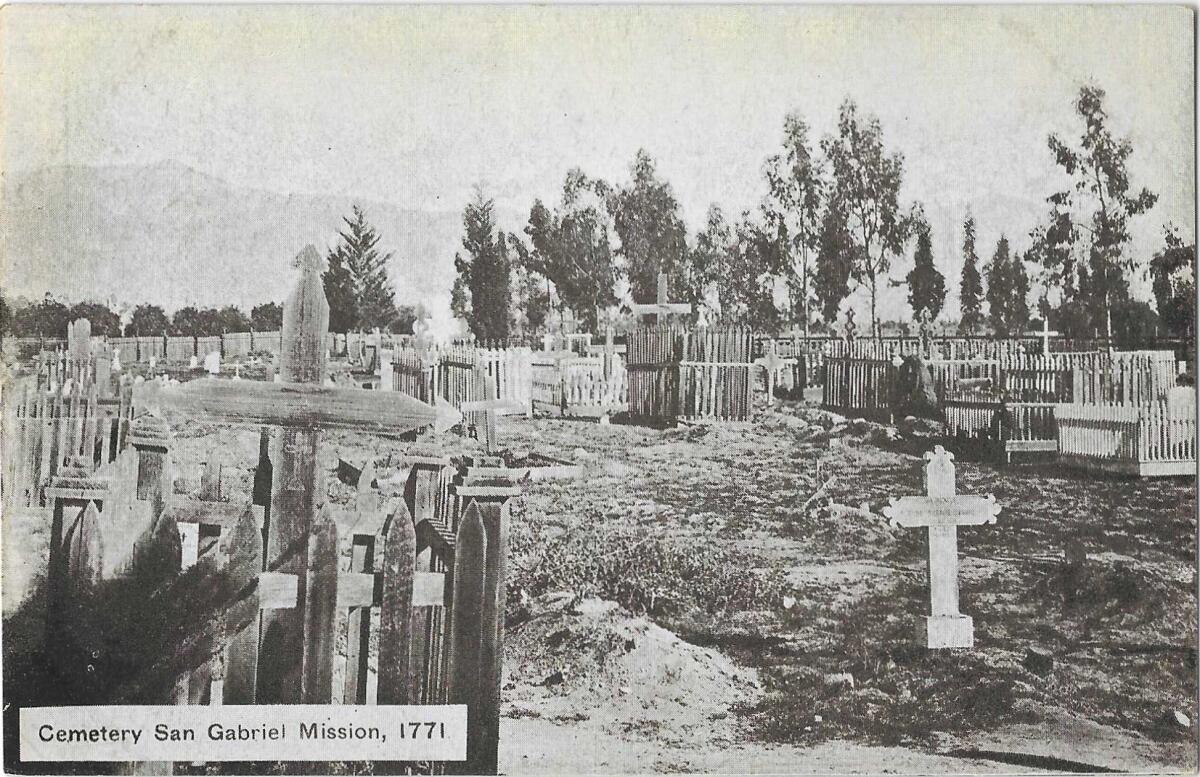

Now, set your time machine on fast-forward, to the mission era, the late 18th and early 19th centuries. That was a closed-loop cemetery system: the nonnative Americans living here were perforce Spanish and Mexican, and Catholic, and often buried in mission graveyards. So too were many of the Native American converts who were forced into labor in the missions, but often in unmarked and even mass graves.

The Mexican War brought in Protestant Americans, civilians and soldiers. Where to bury them? Rich pioneer Yankee families built family burial grounds. William Workman installed a cemetery east of the family house in the present City of Industry, walled it in brick and fenced it in iron rails. Its first occupant? His brother, David Workman, killed in a fall off a cliff as he rode a mule in the dark in search of a lost heifer.

The present-day historic Wilmington Cemetery also began as a private burial ground more than a century and a half in the past. Phineas Banning, the Yankee go-getter who earned his nickname “the father of the port,” needed to bury his 2-year-old son.

In the present life as a public interment ground, Wilmington Cemetery ticked all the check marks of far too many historic cemeteries in need of remedial care: neglect as families died off or departed, poor management and even poorer maintenance, an unending series of owners. In 2008, a family found a stranger’s bones and wooden coffin splinters in a plot they had bought and paid for.

In the mid-19th century, poor Angelenos could wind up in Ft. Moore Hill. It was briefly a fort during the Mexican War, then was variously called Fort Hill, Cemetery Hill, the City Cemetery, and School Hill, home to the city’s high school and later school district headquarters.

It became city property in about 1853, a cemetery and, conveniently, a hanging grounds. Among its first eternal residents was a mountain man who killed a grizzly bear and vice versa somewhere out in Malibu. Andy Sublette’s coffin was accompanied by his dog, Old Buck, himself injured in the bear battle. Buck lay down at the new grave and soon died, and may even have been buried with Sublette.

The city’s poor were buried with no ceremony, and many of the 19 victims of the city’s disgraceful 1871 massacre of Chinese residents were originally buried here. Rumors also wafted around town of the bodies of Native Americans simply rolled into the ravine below the hill.

Bob Hope, along with Daffy Duck and Marlene Dietrich, helped popularize the catchphrase ‘Now you’re cooking with gas.’ Many decades later, we’re paying out the nose for the privilege.

This cemetery, like so many to follow, was swiftly filled, or nearly so, and then left to disarray. In 1876, after the city had found more profitable demand for the hilltop — lordly houses, and a beer garden — there came ghoulish warnings about “pestilence-spreading gasses which are given forth by decomposed and decomposing bodies.”

As late as 1909, The Times fretted that the high school’s track and field athletes were forced to hurdle graves and dodge tombstones for want of a proper field, and that “in warm weather, the place makes a good sleeping ground for many tramps and hobos.”

Eventually, identified bodies were slowly moved to the new Evergreen and Rosedale cemeteries. The last graves would not be removed until 1947, but most had already been carried off to two of the city’s haphazard pantheons: Evergreen, in Boyle Heights, founded in 1877, and Rosedale-Angelus, opened in 1884 in the then-faraway neighborhood of West Adams.

Reading Evergreen’s gravestones is reading Los Angeles history: Hollenbecks, Van Nuyses, Lankershims are here. So is Biddy Mason, the former slave who made herself free, then became a philanthropist and one of the richest property owners in town. And Charlotta Bass, owner and publisher of the ferocious Black newspaper the California Eagle. Here are Mary Foy, first woman to head the city library, George A. Ralphs, founder of the grocery chain, and Japanese Americans who fought in the World War II “go for broke” regiment, awarded 21 Medals of Honor and about 4,000 Purple Hearts.

Long ago, the Pacific Coast Showmen’s Assn. bought a substantial plot and buried many of its members here, such as tightrope artist Mayme Butters, cowboy clown Dan Dix, and two circus fat ladies, Emilie Bailey and “Dainty Dotty” Jensen.

At Rosedale-Angelus is a favorite “only in L.A. … and Siberia” grave — that of Anna Rasputin, daughter of the “Mad Monk” who helped pull the plug on the Romanov dynasty. His daughter retired here after doing an animal act for Ringling Brothers. The developer-dentist David Burbank, who gave his name to the city, is here, and so is the L.A.-born Anna May Wong, the gutsy, groundbreaking Chinese American actress.

Evergreen and Rosedale were always remarkably ecumenical, permitting burials of people of color and non-European ethnicities — but in separate sections. Hattie McDaniel, the first Black actor to win an Oscar, is at Rosedale. When she died, in 1952, Hollywood Memorial Cemetery wouldn’t honor her wish to be buried there. Decades later, what is now Hollywood Forever made amends by raising up a monument to her.

Hollywood Forever, founded in 1899, is, unusual among old L.A. cemeteries, assiduously tended, with attractions for the sprightly living — yoga classes, author events, summer movie screenings and party spaces; I once went there for an after-party for a season premiere of “The Walking Dead.”

It abuts Paramount Studios, which sits on land bought from the cemetery. The Jewish section — begun under different ownership in 1927, the year the Talkies took Hollywood by storm — is decades younger than L.A.’s oldest Jewish cemetery, in Chavez Ravine.

Antisemitism is as old as time. In Los Angeles, prejudice against Jewish people took on new and more public forms in the 1920s and 1930s and beyond.

Beginning in 1855 , the city’s early Jewish families buried their dead on three acres in the ravine, close to Boyle Heights, then the deep footprint of Jewish life. Yet over a half-century, the city’s grimy commerce climbed that hill. Smudge-ugly oil derricks befouled the graves, and by around 1905, graves and gravestones had been moved to a new Home of Peace, well east of downtown.

The land was completely in public hands by 1943, meant for a housing project that was never built. Instead, L.A. got Dodger Stadium, and in 1965, Sandy Koufax, the left-handed Jewish pitcher from Brooklyn, pitched the Dodgers’ only perfect game, on the site of L.A.’s first Jewish cemetery.

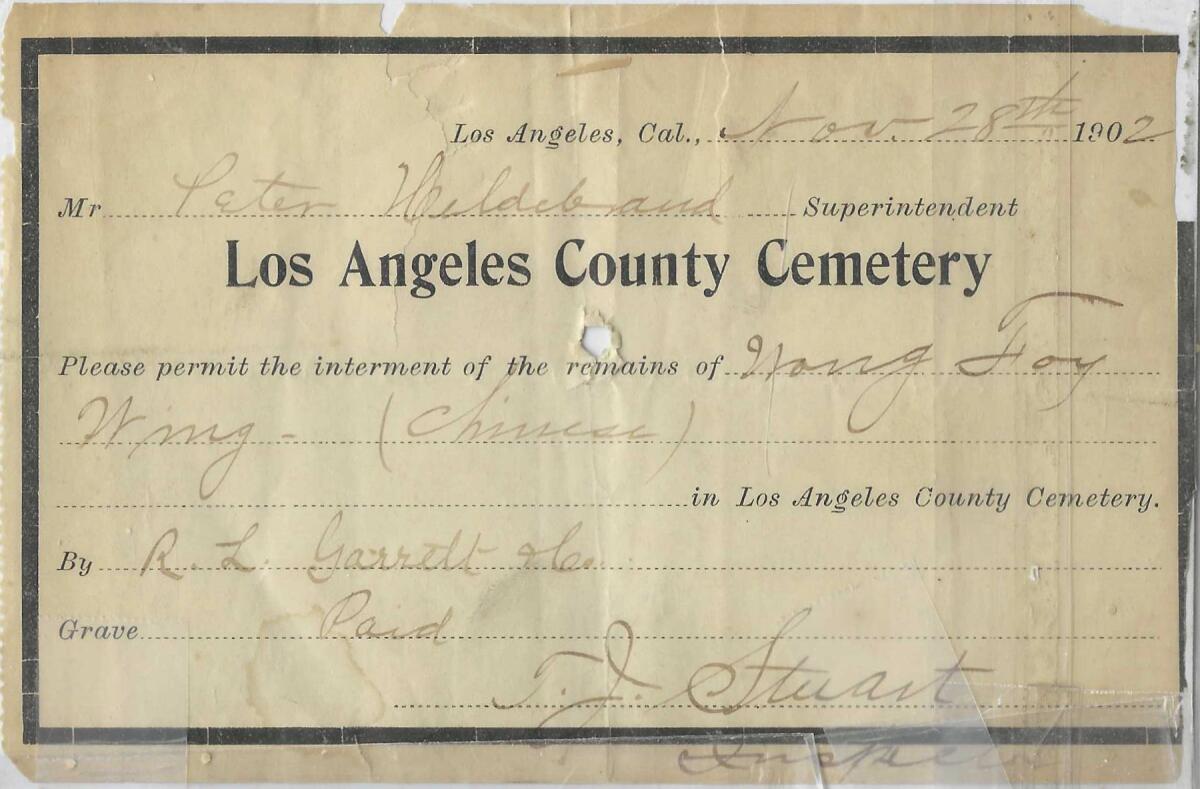

Not far from the present Home of Peace is the Chinese cemetery. The Chinese, barred from this country by law in 1882, were often barred from burial too.

Even in Evergreen, where others were buried for free, Chinese families had to pay $10 to entomb their dead.

I mentioned earlier that newspaper publisher Charlotta Bass was buried at Evergreen. In 1951, her newspaper’s series, “Burial Scandals,” exposed the segregation practices of local cemeteries. It reproduced a 1931 Forest Lawn space application requiring the buyer to certify “that he is of the white Caucasian race and that he will not inter or attempt to inter the body of any human being other than that of the white Caucasian race …” All such practices were banned by law in the 1960s.

If cemeteries’ decay and mismanagement weren’t enough to give you the frights, let’s not overlook their ghosts. Instead of what you’d expect — legions of them, rising up in gory phantasmagoria — I encountered accounts of very few, chiefly demure lady ghosts, swathed in white, blue, or pink, like Disney princesses.

San Juan Capistrano, with its mission as old as the Declaration of Independence, seems to have the highest count: a misty “white lady,” who poisoned herself on the front porch of the lover who jilted her; the spirits of some two score Native Americans killed when a December 1812 earthquake collapsed poorly mortared mission walls as they were at Mass; George, a cigar-smoking spirit in a plaid shirt; and the Baskervillian mascot of all ghostly encounters, a red-eyed devil dog.

At El Toro Memorial Park, also in Orange County, circa 1896, the ghostly lady is enveiled in otherworldly blue, and she sobs among the gravestones. Maybe she is kept company by a man who died in the early 1980s and told his family to dig him up after 90 days, because he’d be coming back to life. They did, and he didn’t.

I was once assigned to camp overnight in Yorba Linda’s historic cemetery, waiting with ghost-spotters for the teenaged Pink Lady. Pink was the color of the gown she was wearing when she died in a buggy crash coming home from a cotillion. She too was a no-show, at least to my skeptical peepers.

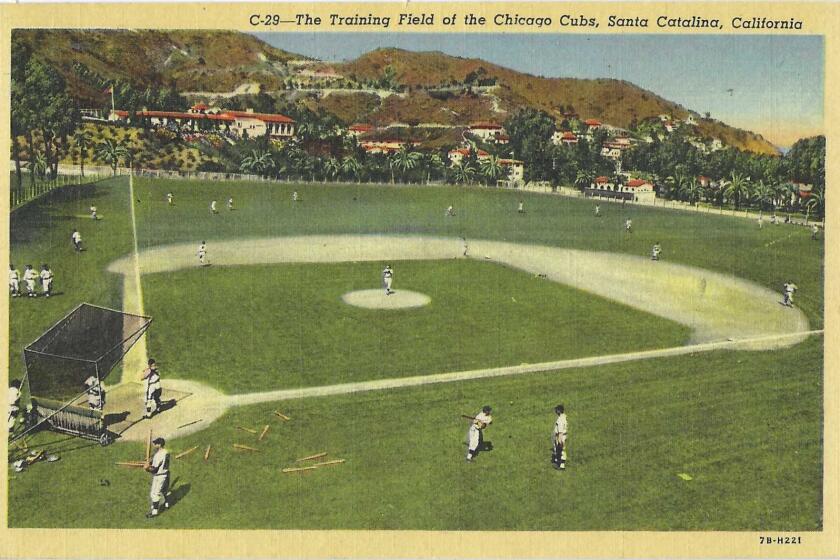

The Cubs held spring training on Catalina Island. A team called the Tigers played in Vernon, then Venice, then Vernon again. And L.A.’s Wrigley Field held night games decades before Chicago’s did.

Hollywood has programmed me to think of “Frankenstein” movies if anyone mentions grave-robbing, but it’s the jewels, not the jowls, that are the attraction.

In 1925, about halfway through Prohibition, an L.A. County district attorney passionately declared to a class of police cadets: “If I had to choose between robbing graves and being a bootlegger, I would not hesitate a moment but would tumble the dead out of their coffins and take from their cold, clammy fingers their few trifling ornaments. I could not harm the dead by despoiling their bodies, but by selling poisoned whisky, I would corrupt the souls of the living.”

He seemed nice.

From a family vault at the old Calvary Cemetery, in 1903, the body of Dona Maria Alvarado de Pico, dead nearly 50 years, was dragged out and left some 50 feet away. The skeleton was found with its still-gloved hands crossed upon its chest. The body of her husband, Pio Pico, an African-Latino descendant of L.A. “pobladores” and the last Mexican governor of California, was untouched. If grave robbers expected to find treasure entombed with these two bearers of fabled names, they had not done their homework. Pico was once rich beyond the dreams of avarice, but he died so steeped in debt that a collector snatched the very sombrero off his head to sell for his creditors.

Where the old Calvary Cemetery stood is now Cathedral High, whose mascot is the Phantoms.

So Angelenos, if you’re going to do the tourist celebri-grave thing, get out a map, fire up an app and visit your underground history too.

Forest Lawn’s SoCal “memorial parks” you likely already know, the place Smithsonian magazine called the “Disneyland of graveyards.” So here are some other places to visit:

- Altadena’s Mountain View, 60 foothill acres, with my favorites, Caltech physicist Richard Feynman, the Black sci-fi author Octavia Butler, and quirkiest of all, a-moldering in his grave, Owen Brown. A son of the incendiary abolitionist John Brown, Owen fought with his father in the 1859 raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. He escaped the noose, eventually moved west, and lived with a brother in a foothill cabin.

- The private Marquez family cemetery, in Santa Monica Canyon, is the last scrap of land surviving as a burial ground from its Rancho Boca land grant days of more than 180 years ago. Its most spectacular dead: 13 people all felled by botulism poisoning from home-canned peaches at a New Year’s Eve gathering in 1909.

- Rosemead’s Savannah Memorial Park began the year California became a state, 1850, and was many dead Protestants’ only alternative to Catholic graveyards. Notable resident: William “Billie” Dodson, a vaudeville female impersonator and popular society milliner.

- Sylmar’s Pioneer Cemetery, a place that history lovers have battled for so long to preserve and restore. In its parched acres are said to be some of the uncounted and unknown dead from the 1928 St. Francis dam collapse, many of them Latino workers and their families.

- Shared by Burbank and North Hollywood, Valhalla Memorial Park, opened a few years before Charles Lindbergh soloed across the Atlantic, had its past share of fraud and neglect. But the spectacular 1953 Portal of the Folded Wings, dedicated to aviation pioneers, proves that marble angels aren’t the only graveyard denizens that took to the air.

For the record:

11:03 a.m. March 8, 2024This article includes an incorrect burial place for Owen Brown. Brown is not buried in Mountain View cemetery, but on a hilltop a few miles away. Brown’s sister and brother-in-law are buried at Mountain View, and Brown has a plaque in the cemetery’s mausoleum.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.