Lunar New Year traditions were abstract until my grandmother died

Most years, I visit my family in Taiwan for Lunar New Year. And each trip, since I was very small, I have found myself before a family altar, with a stick of smoking incense in my hands, wondering exactly what I’m supposed to do, think or say.

None of my Taiwanese relatives ever offered any instructions that I can recall. In the convoluted balancing of family needs and desires that happens on these trips back home, a 7-year-old’s confusion does not carry much weight. My strategy has been to bow when everyone else does and affix an appropriately solemn expression on my face.

But something clicked during this year’s trip to Taiwan, when I went with my aunts to light incense at the temple to honor our ancestors. And a lot of that has to do with my grandmother, who died in 2021.

My grandma was the strongest person I knew. She had no schooling, but she raised four daughters and a son by herself after my grandfather suffered a car accident when my mom was young. She was a single mother and a subsistence farmer who raised chickens and grew rice and sugarcane in the fields near our family home in Hsinchu.

She did odd jobs in exchange for eggs, fruits and vegetables to feed the family, and grew cabbage in their backyard. She saved up money to start her own convenience store, and the money from the store became a boarding house for university students that now stands five stories tall. Her efforts raised our family from poverty to the middle class in Taiwan in a single generation.

I never got to talk to my grandma. She spoke Taiyu, a Taiwanese dialect, and I spoke Mandarin, and we could only afford to visit once every few years, for a few days. But every time we arrived, there was a massive feast waiting with all of our favorite foods along with endless plates of cut wax apples, guavas and oranges. Even though we couldn’t understand each other, she could always make me laugh. She always made an effort to talk to me anyway. I would nod and she would laugh, because I was only pretending to know.

She was fierce and dominant and hilarious. She had an earthy, mischievous sense of humor and a booming voice that you could hear throughout the whole house. When she spoke, my loud, chaotic family went silent. I remember falling asleep to the sound of my aunties laughing.

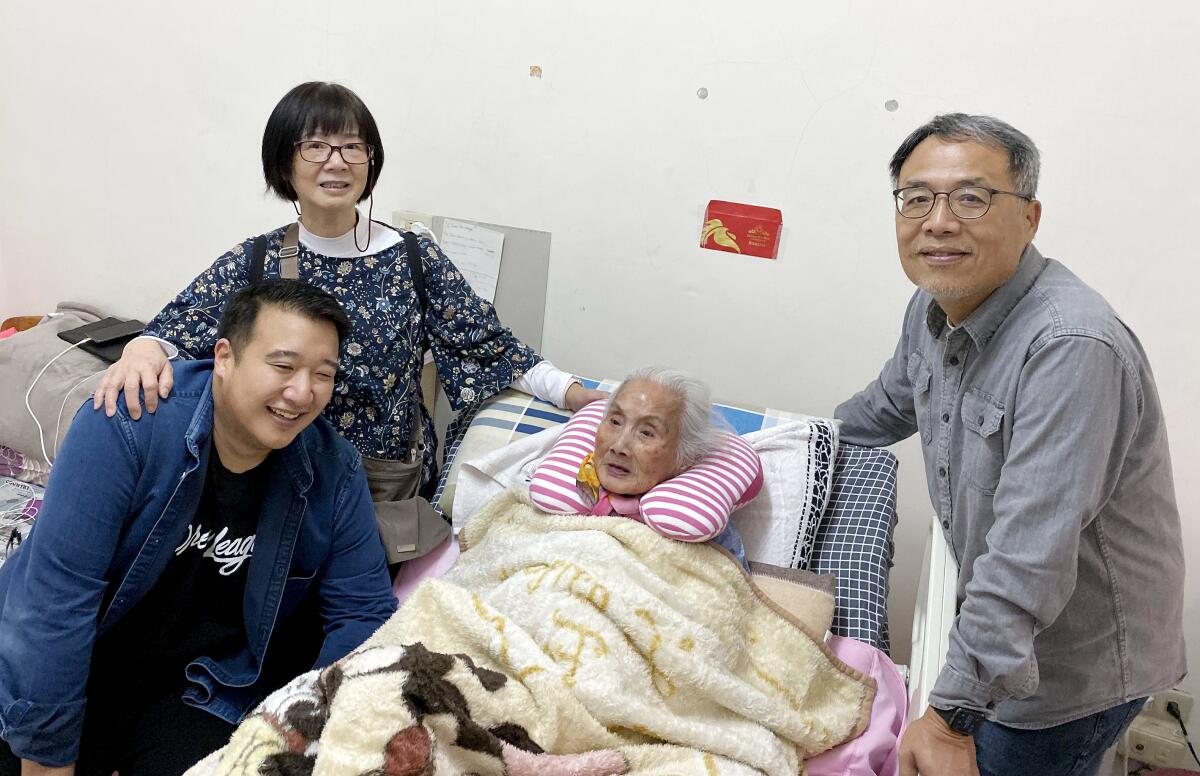

But she had a stroke in 2018 that took away her ability to speak. The house in Hsinchu went quiet. Just the creak-clank, creak-clank of her walker and the echoing claps of our house slippers on the tile floors. Over the dull roar of passing vehicles, I would overhear fearful whispers in Mandarin about her health and medical care, which always shifted to Taiyu when I was around. But I kept visiting. Each time, as soon as I arrived, she would say the name of my favorite dish and, using only her eyes, silently command my aunties to fetch it for me.

When she passed away, none of us were ready. Her passing tore a hole in a family that had already lost too much, too soon. My uncle died young in a construction accident and we lost my grandfather before I was born. She was the star we orbited, our center of gravity, and without her, we were adrift. I had always imagined I would learn her language and surprise her one year, but now I was too late.

This year, I visited Taiwan for the first time since she died. Her remains are stored in one of a series of ornate lockers in the columbarium of a Buddhist temple in Hsinchu, second from the bottom, just a few feet away from my uncle, her son.

We lighted incense, then knelt in the narrow hallway and clasped our hands. Suddenly the language wasn’t important. Pent-up words poured out.

I thanked her for raising my mother to be strong, and I promised her I would take care of her daughter. I told her that I am here because she persevered and that I’m glad she is resting now. That we miss her, and though things will never be the same without her, we will keep her memory alive and always move forward.

I have never been religious or superstitious, and I’m not aware of which sect of Buddhism we identify with. But this year, I saw my grandmother. I heard her in the fond stories told to fill long silences. I recognized her in the faces of my mother and aunties. I felt her love in the strength of their devotion and the depth of their grief.

When we drove by the family home, I tasted her cabbage omelet and the gong wan that she made from scratch. I remembered how her hands felt in mine, warm, deeply lined, callused from a lifetime of hard work.

For children of immigrants growing up with American pressures and influences, these traditions can feel like a dusty, boring waste of time. Our parents aren’t always good at explaining, because they often don’t understand either. But I’m writing this because I believe that a time will come when tradition will be a comfort and a release.

Traditions exist because we want to honor history, but I think we keep them around because we need them. For people who were taught to never let hardship stop the work of life, the temple allows us to release grief and offers a space in which to resurrect our loved ones through memory.

Grandma, I think I understand now. I light this incense in the hopes that this smoke might carry my words to you. We come here every year so that, across this bridge of tradition, we might meet again, if just for a moment, and find the strength to bear the pain of parting for one more year.

I light this incense because it’s too hard to say goodbye, forever. Sometimes it is easier to say, see you next year. And every year after that.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.