A massacre that killed 6 reveals the treacherous world of illegal pot in SoCal deserts

In a desolate stretch of California desert off U.S. Highway 395, Franklin Noel Bonilla made one last desperate plea to save his life.

“I’ve been shot,” he told 911 dispatchers in Spanish, according to authorities. “I don’t know where I am.”

Officials tracked the coordinates of the phone call to a dirt road in the remote desert community of El Mirage, about 50 miles northeast of Los Angeles.

There they made a horrific discovery: six men with gunshot wounds, four of them with severe burns, and two abandoned vehicles, one of which was pocked with bullet holes.

Authorities think the massacre was the result of a dispute over illegal marijuana, and it marks the latest act of shocking violence in isolated areas of California where a black market for pot has flourished.

The death toll, which has included shootings and dismemberments, has alarmed law enforcement officials and comes as illegal grow operations have spread in inland desert communities across Southern California.

California’s legalization of recreational cannabis in 2016 ushered in a multibillion-dollar industry. But many of the promises of legalization have proved elusive.

Hundreds of pot farms have cropped up across the desert region, bringing crime and fear with them, according to residents and law enforcement officials.

In the last year alone, the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department said its marijuana enforcement teams served 411 search warrants for illegal marijuana grows. They found 14 “honey oil” labs, 655,000 plants and 74,000 pounds of processed marijuana. Eleven search warrants were executed in the immediate area where the slayings took place.

“The plague is the black market of marijuana and certainly cartel activity, and a number of victims are out there,” Sheriff Shannon Dicus said.

A Times investigation last year uncovered the proliferation of illegal cannabis in California after the passage of Proposition 64, which legalized the recreational use of marijuana in the state. Although the 2016 legislation promised voters that the legal market would hobble illegal trade and its associated violence, there has been a surge in the black market.

Growers at illegal sites can avoid the expensive licensing fees and regulatory costs associated with legal farms. Violence is a looming threat at these operations, authorities said, because illicit harvests yield huge quantities of cash to operators who can’t use banks or law enforcement for protection.

Commercial cannabis resulted in corruption and questionable conduct that has rocked local governments across California, a Times investigation found.

In 2020, six people were found shot to death at a property in Aguanga, a small community in rural Riverside County east of Temecula. A seventh victim later died at a nearby hospital.

The victims were immigrants from Laos and were found at a large-scale illegal marijuana cultivation and processing site — a “major organized-crime type of an operation,” Riverside County Sheriff Chad Bianco said at the time.

It is hard to determine the number of homicides tied to illegal pot farms. But a Times review in 2021 found at least five Mojave Desert killings in 2020 and 2021 that investigators said were connected to pot farming.

Black markets can thrive despite the legalization of the product, according to Peter Hanink, a professor of sociology and criminology at Cal Poly Pomona.

“It doesn’t matter what the product is,” he said. “If there’s sufficient demand and the thing is valuable enough, you’ll get a black market.”

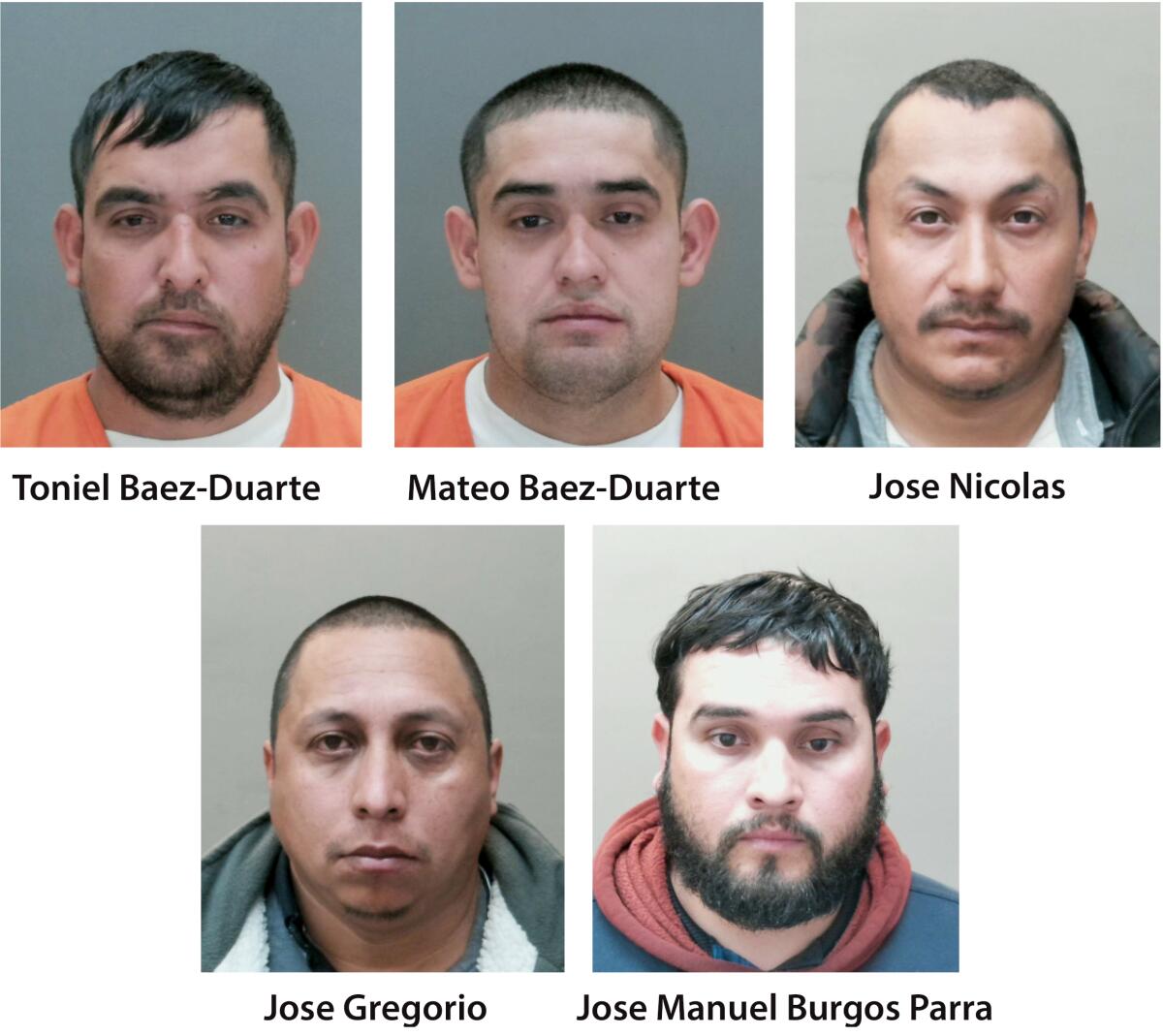

Five men have been arrested in a gruesome multiple slaying in a remote area of the Mojave Desert. Six men were fatally shot, and four of them also were burned, in Tuesday’s incident, authorities say.

Cartels in Mexico have traditionally carved up and delegated certain areas to different groups so they don’t have to kill each other to make money, Hanink said. At the beginning of a black market, when there’s more instability, there could be violence that results from regional groups competing over the same area. Hanink said the El Mirage slayings could’ve been between competing groups, based on the grisly nature of the crime.

“The sheer violence and the extent of the violence — burning the bodies and how extreme it was, it’s the sort of thing that suggests someone is trying to send a message,” he said.

Hanink stressed, however, that he doesn’t believe Mexican cartels were involved in the San Bernardino County killings, because the FBI, Homeland Security and the Drug Enforcement Administration haven’t gotten involved. The fact that the investigation involves only the Sheriff’s Department and the California Highway Patrol indicates it’s a local California matter, he said.

“Mexican cartels tend to stay local to Mexico, and they very rarely try to do things within the U.S. because they don’t want to involve U.S. law enforcement,” he said. “If you have executions being ordered by parties in other countries, that becomes a case of U.S. security interest.”

Bill Bodner, former special agent in charge of the DEA’s Los Angeles Field Division, agreed that while Mexican cartels have previously been involved in the illegal marijuana business, most have shifted to synthetic drugs, such as methamphetamine and fentanyl.

Illegal marijuana trade has also become unprofitable for the cartels, he said, because of the risk of getting shipments seized at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Bodner said disputes at illegal grows usually involve the theft of product or cash and, in some cases, workers seeking to get paid.

“Don’t forget, it’s a criminal business run by criminals, so they’re going to pay as little as they can,” Bodner said.

The marijuana black market has thrived in California in recent years, as growers try to circumvent taxes, feeding an unlicensed, unregulated industry and, at times, making its way into legitimate dispensaries as well, Bodner said.

In 2019, an audit by the United Cannabis Business Assn. found nearly 3,000 unlicensed dispensaries and delivery services were operating in the state — at least three times more than legal, regulated businesses.

Four years later, Bodner believes the black market has only gotten larger in California.

“The number of unlicensed grows, conservatively, has doubled,” he said.

California has largely ignored the immigrant workers who harvest America’s weed. Their exploitation is one of the most overlooked narratives of the era of legal cannabis.

At first, deputies saw cardboard, rubber tires, broken bottles and bullet casings littering the ground when they drove out to the remote El Mirage location on Jan. 23. There were two abandoned vehicles nearby, one of them riddled with bullet holes. Then they found the bodies.

Four of the six victims have been identified: Franklin Noel Bonilla, 22; Baldemar Mondragon-Albarran, 34; and Kevin Dariel Bonilla, 25. The fourth is a 45-year-old man, whose identity is being withheld pending notification of next of kin. They were all Latino, possibly Honduran nationals, and lived in Adelanto and Hesperia, authorities said.

After the brutal slayings, the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department served search warrants in Apple Valley, Adelanto and the Los Angeles County area of Piñon Hills. They arrested five men in connection with the killings — Toniel Baez-Duarte, 34; Mateo Baez-Duarte, 24; Jose Nicolas Hernandez-Sarabia, 33; Jose Gregorio Hernandez-Sarabia, 34, and Jose Manuel Burgos Parra, 26.

Authorities say they believe everyone involved in the killings has been arrested and there are no outstanding suspects.

When serving warrants, detectives recovered eight firearms. They will undergo forensic examinations to determine whether any were used in the slayings, said Michael Warrick, a sergeant in the specialized investigation division of the Sheriff’s Department.

Warrick wouldn’t comment on whether the slayings were cartel-related but said there were “certain things at the scene that show a level of violence that obviously raises some interesting questions for us.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.