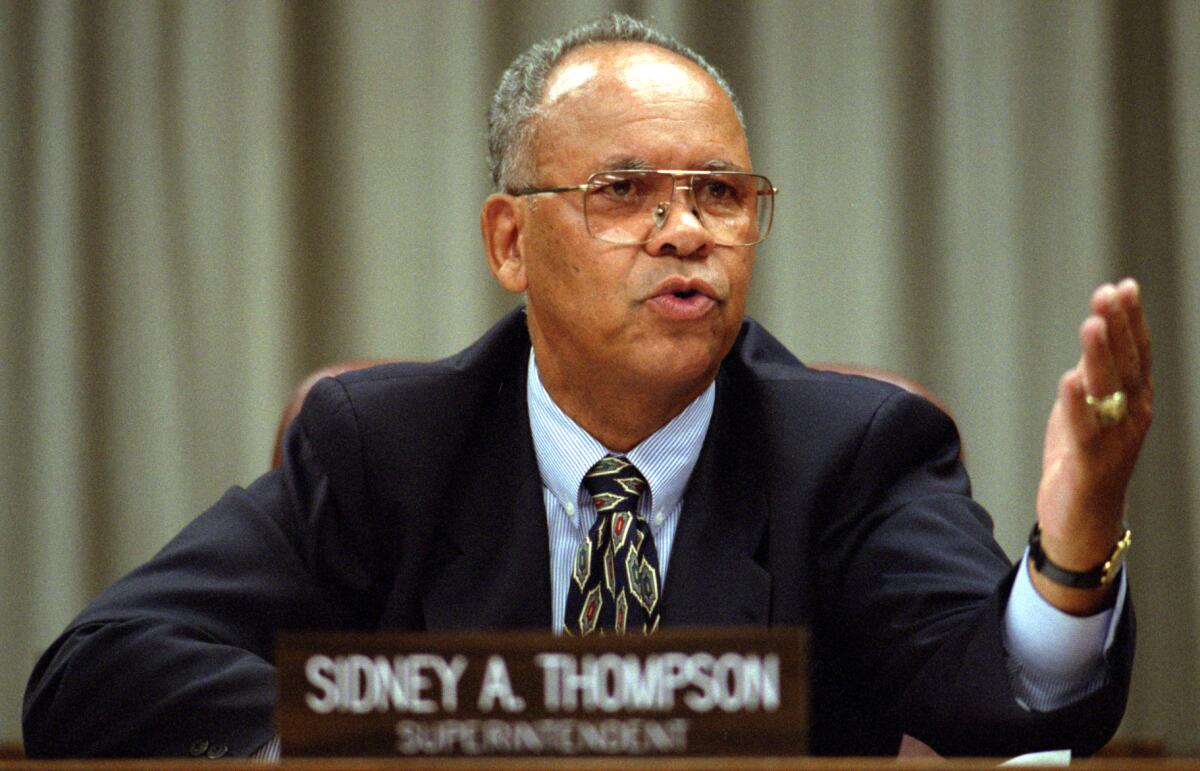

‘He was unflappable.’ Sidney A. Thompson, first Black LAUSD superintendent, dies at 92

Sidney A. Thompson grappled with crisis after crisis as Los Angeles Unified schools chief: racial tensions, labor strife, the Northridge earthquake, financial shortfalls that brought the district to the brink of insolvency.

The first Black superintendent of the nation’s second-largest school system also oversaw the district’s most aggressive academic reform attempt — which ultimately failed, but not because of him. Along the way he maintained the respect of allies and adversaries alike.

“He was unflappable. And I can’t tell you how valuable that is,” said former school board member Mark Slavkin. “It was never about Sid. It was about what needed to happen.”

The veteran school district leader died Dec. 2 at Huntington Hospital in Pasadena of congestive heart failure, his daughter Theresa Carter said. He was 92.

When Thompson became the leader of L.A. Unified in October 1992, the district was in crisis. Two years earlier, then-Supt. Leonard Britton — brought in from Miami — had run aground against a teachers’ strike, disgruntled subordinates, a contentious school board and an economic downturn. Then, his successor, local favorite William R. “Bill” Anton, quit midterm amid worse finances and a looming second strike.

Many considered Thompson’s selection overdue, while others were lobbying for a Latino in a Latino-majority school system, another flashpoint for Thompson to manage with his trademark self-effacing poise.

He first stepped in as interim leader, then received a three-year contract.

He was soon confronted with a threatened teachers’ strike — which would have been the second in three years — after the district could not afford agreed-on pay raises amid a state budget crisis. Thompson leaned in with the help of state Assembly Speaker Willie Brown (D-San Francisco) — who found some state funding to soften the blow of a teachers’ salary cut that still reached 10%. Thompson and the school board agreed to significant non-pay concessions, giving control to teachers over choosing classes and influence to all unions over health benefits.

“This is a talented, sensitive man who understands human relations as well as anybody I have ever seen,” Brown said of him at the time, adding, “He is literally in an impossible situation.”

It helped that Thompson and tough-as-nails teachers union leader Helen Bernstein actually liked each other, although it would have been politically untenable to show it.

“There will always be tension between the union and the superintendent, but Thompson was not a superintendent that went looking for confrontations,” former United Teachers Los Angeles President John Perez said. “He never seemed to me to be a ‘my way or the highway’ kind of guy. He understood that the state shortchanged schools, and he felt that we all had to work together to give our students the best possible education we could.”

A natural disaster — the 1994 Northridge earthquake — damaged 160 schools, closing many of them for weeks. The school system had been unprepared, but most people trusted that Thompson made a good-faith effort to restore order.

In the 1990s, L.A. Unified was overcrowded and struggling especially to educate Black students and non-English-speaking Latino immigrants. Court-ordered integration had led to white flight. State test scores were low. Civic discontent with the district prompted calls to break up the school system.

“He became superintendent at a time when the board was deeply divided,” said former school board member Leticia Quezada, who described Thompson as trustworthy and sincere. “It would have been impossible to have a superintendent who had his own agenda.”

Instead, that direction came from the outside.

A “last-chance” coalition improbably brought together teachers union leader Bernstein with corporate powerhouses such as future Mayor Richard Riordan, under an organization convened by former veteran state lawmaker Mike Roos. The effort was called Leadership for Education Accountability and Reform Now, or LEARN.

The goal was to let school communities — instead of the central office — control budgets, hiring and academic decisions. Schools would be run by a committee that included the principal, teachers, other staff and parents. Teachers in particular had a more powerful voice than ever. For parents, it was typically the first time they’d had any voice at all in school decisions. Principals had to learn to “build consensus” for what they wanted to do.

Initially, school faculties had the option of voting themselves into the plan — with the perk of getting additional funding. Ultimately, all schools were to be moved into this format.

A corporate-dominated board oversaw the effort from the outside — Thompson had to report to its members as well as the frequently sparring elected school board members. Many long-term district insiders believed that LEARN was improperly imposed from the outside. But Thompson pressed forward with the plan.

“He was probably the most stalwart backer of what was the most ambitious reform plan the district ever attempted,” said Charles Kerchner, professor emeritus at Claremont Graduate University and a historian of the period. Thompson’s affability, he added, could disguise his intelligence and his street-fighter doggedness.

Roos also expressed admiration: “Every day people around him were throwing brickbats at him, saying: “Why are you doing this? This is creating problems in our lives.’ And he just stood firm.”

After a five-year tenure, Thompson elected to retire in 1997. That same year, Helen Bernstein died in a traffic accident. Roos stepped aside in 1999. And corporate and civic leaders moved on to other interests or other strategies, such as privately run, publicly funded charter schools. The LEARN initiative never fully took hold and gradually faded away.

Thompson then began a second, long-running professional life as a trainer of future education leaders at UCLA, where he was well liked and respected — as he had always been.

Thompson was born on May 9, 1931, in Los Angeles, the second of five children of Brennan Thompson, an educator and electronics worker who became an aerospace technician, and Cecily Hazel Thompson. His parents immigrated separately from the West Indies, meeting in the United States. After his birth, they moved briefly to the island of Bequia in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, where Thompson attended a public school built atop stilts on the beach until second grade.

He graduated from Belmont High, just west of downtown L.A., and had to overcome the advice of counselors who suggested that he and other Black students get jobs rather than aspire to a higher education.

His love of the sea took him to the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, from which he graduated in 1952. He served on the USS Rochester as a lieutenant during the Korean War.

Post-Navy, he applied in 1956 for a teaching job at L.A. Unified, which needed math instructors.

He quickly became the popular young teacher at Pacoima Middle School, who played touch football with the boys after school, broke up fights and could actually teach.

In 1957, two planes collided overhead, sending flaming debris onto the playground. Two children died; others were seriously injured. After Thompson made sure his unharmed students were supervised, he rushed into the melee, wrapping his suit jacket around a student whose clothes had burned off him, possibly saving his life.

Carter, his daughter, remembers that, later, as principal at Crenshaw High, her father would rush into trouble to break up fights or defuse gang tensions, frequently coming home with torn pants.

He raised four children as a single parent, rising steadily at work, promoted for competency, leadership and following orders loyally.

Years later, Thompson, after attending a mentor’s funeral, lauded the man in terms that came to define Thompson: “This was someone who could meet every type of person from every level and yet had a way of having them believe that they were important to him because they were.”

Thompson is survived by three daughters and a son and two stepchildren, as well as grandchildren and great-grandchildren. His 1952 marriage to Dorothy Smith ended in divorce, as did his 1977 marriage to Julie Narvaez.

A public memorial will be held at 11:30 a.m. Jan. 19 at Inglewood Cemetery Mortuary.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.