Column: Blame ketamine for killing Matthew Perry? It’s saving someone I love

Every day for the last eight months, someone I love dearly has strained to find a reason to live.

There is no trauma that caused this, no single reason that can be fixed, not even really a desire to die. It’s just nothingness. My loved one has serious depression, and being in this world feels like a burden. They would prefer not to exist.

There are about 21 million American adults who experience a major depressive episode each year, so my person is not alone. But they feel as if they are.

We have tried (and continue to try) therapy. We have tried (and continue to try) antidepressants. We’ve tried unconditional love and tough love, exercise and eating right. Depression is stubborn, and cruel.

Faced with consuming fear that this will go on for years, or worse, end in suicide, we started looking outside the rigid and exclusionary boxes of mental health treatment that define our broken system of care. That search brought us to ketamine therapy, which my person (who is OK with me sharing their story) started a few weeks ago.

And then came Matthew Perry, and a ruling by the Los Angeles County coroner’s office that the death of the beloved “Friends” actor was primarily due to “acute effects of ketamine.” When I read the headline in this paper, I couldn’t breathe.

Was I about to find out the treatment we had turned to with equal parts desperation and hope was more dangerous than the disease, like one of those Big Pharma commercials in which the disclaimers are so dire they seem absurd?

But after reading the autopsy report and speaking with experts and patients who use ketamine, it turns out the truth is more complicated, as most things with mental health are. Perry did not die because he was using ketamine to treat depression or addiction, and for the sake of a therapy that is both effective and only just making it into the mainstream, it’s important we get the facts in full.

“People shouldn’t be frightened away from treatment because of this,” Dr. John Krystal told me.

He’s a professor at Yale School of Medicine and its chair of psychiatry. In the 1990s, Krystal pioneered the use of ketamine to treat depression. Since then, a multitude of peer-reviewed studies have proved what he sees in his patients every day — ketamine curing or controlling serious depression, sometimes overnight.

“It is a remarkable thing to see,” he said.

Those sometimes fast-acting effects give people “the faith that if you stick to treatment, you will continue to do well,” Krystal said, possibly igniting a lifesaving flicker of optimism for those who have wandered through a long, dark labyrinth of failed medications.

One recent study by researchers from Harvard and Mass General Brigham, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found ketamine to be more effective for battling treatment-resistant major depression than electroconvulsive therapy, still considered the gold standard despite its side effects and the trauma that the procedure itself causes for some. More than half of those given ketamine showed improvement, compared with about 41% for those receiving ECT.

In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved a version of ketamine (ketamine is made up of two isomers, or molecules, that can be split apart) called esketamine, for treatment of depression. It’s a nasal spray, and in one study, 70% of people who used it along with an antidepressant showed improvement. Krystal called it a game changer and at the time explained it wasn’t a Band-Aid on depression, but a true cure.

“When you take ketamine, it triggers reactions in your cortex that enable brain connections to regrow,” he said, meaning ketamine has the potential to help the brain rewire itself, rather than just mask symptoms.

Perry had long fought depression and addiction, and like thousands of others, turned to ketamine after other options failed, trying the treatment at a Swiss clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It felt “like a giant exhale,” Perry wrote in his memoir, “Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing,” “like being hit in the head with a giant happy shovel.”

But not every treatment works for every person.

“Ketamine was not for me,” Perry decided after that initial trial, because, “the hangover was rough” and outweighed the momentary relief.

We don’t know what brought him back to ketamine, or whether his latest experiences were different from those earlier ones. It also remains unclear, at least to the public, whether the ketamine he took the day he died was prescribed, or obtained illegally.

It doesn’t matter in one sense; his death is tragic no matter the back story. But in another way, it’s a critical question because for the next decade at least, Perry’s death will be the first thing people think of when ketamine therapy is mentioned. It attaches a stigma to an important treatment, for a disease that is already stigmatized and difficult to treat.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

But what killed Perry was that he drowned, probably passing out prior from a dose of ketamine far higher than what would be used therapeutically for depression — the levels in his blood were more akin to what an anesthesiologist would use to sedate someone. Ketamine was originally developed in the 1960s as an anesthetic.

The physical effect of that mega-dose was perhaps exacerbated further by the presence of buprenorphine in his system, a treatment for opioid addiction. It can put stress on the heart and, at the same time, slow the respiratory system.

But had he not been in water, Perry might still be alive, even with the high amount of ketamine in his blood.

If Perry’s death was the result of a prescription poorly monitored or the abuse of legally obtained ketamine, it throws (or should throw) the spotlight on a nascent treatment that — like medical marijuana a few years ago — is both genuinely therapeutic and also a Wild West of exploitation. There are many legitimate in-person and telehealth professionals providing ketamine, and probably some who are more interested in making money than protecting patients.

A 15-minute online appointment is all it takes to get a prescription for ketamine delivered to your door. That could be a good thing, a lifesaver for some. But it could also just be a quick path to recreational abuse.

Michael Balaban served two tours in Afghanistan, ending up as a gunner on a Black Hawk helicopter. That military service contributed to his diagnoses of complex post-traumatic stress disorder. He was so brimming with unpredictability and anger, he told me, that by the time the pandemic hit, he was basically a shut-in anyway — for the safety of others.

“I was filled with reactivity. Fight and flight was in overdrive,” he told me, though fight usually won. He had tried every antidepressant and anti-anxiety medication he could get his hands on. All of them failed.

On a day he was contemplating suicide, he instead called a local clinic that offered ketamine treatments. Within two months of starting ketamine, his symptoms had abated so significantly that he felt able to take a vacation to Costa Rica.

“It was like I had awakened,” he said. Now, he advocates with a national nonprofit to help other veterans access ketamine.

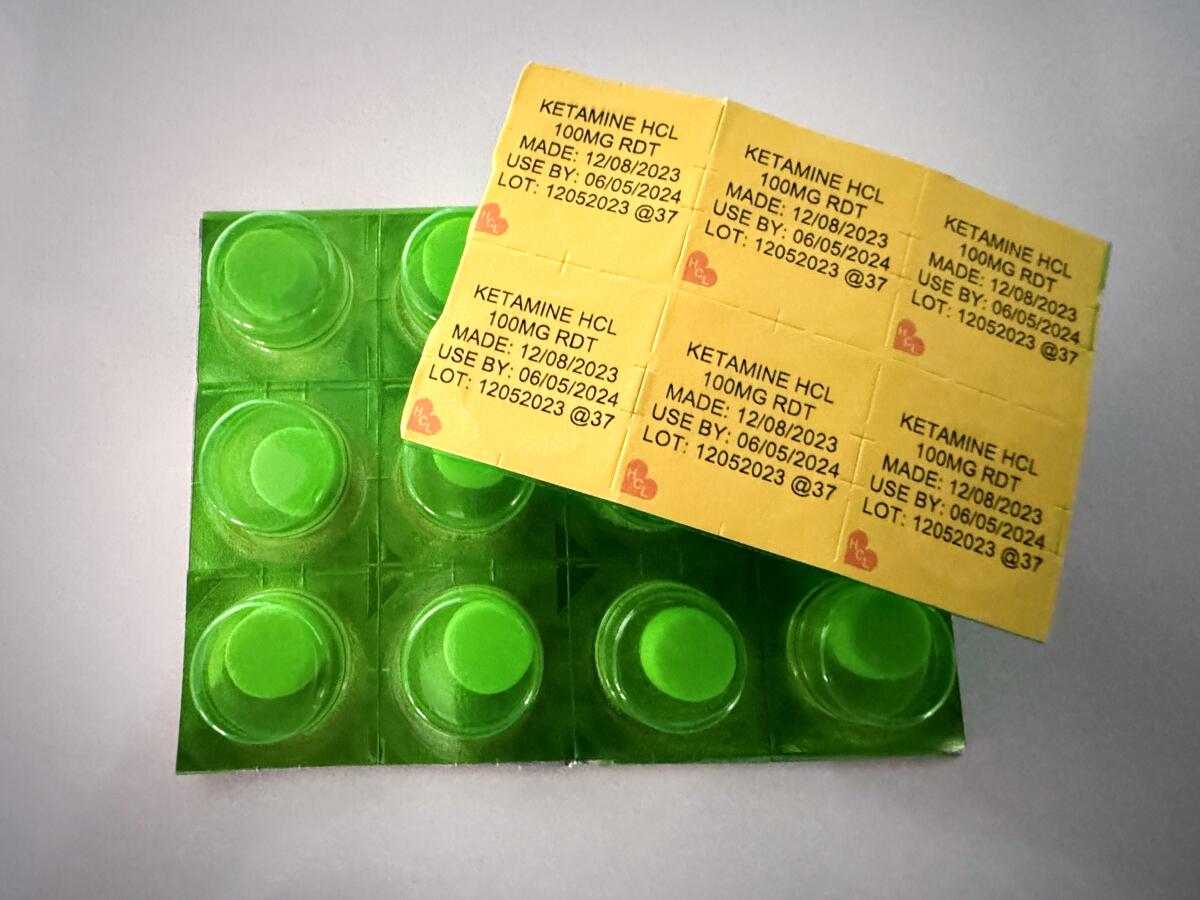

Perry’s death, and the still-fringe nature of ketamine, worries him though. He can’t afford expensive infusions in a clinic, which can cost more than $1,000 each. He relies on a prescription for lozenges he can take at home, costing as little as a few hundred dollars a month.

He is afraid misinformation around Perry’s death and ketamine in general could leave him — and other veterans — without access.

“It’s always the people who are struggling for the access who lose it first,” he said. “My concern is that ketamine infusion and in-clinic treatments will escape the criticism while at-home ketamine, which is one of the only affordable methods, will be the one to suffer.”

The best way to ensure ketamine is used properly — whether in a clinic or at home — is to make it available through mainstream mental health providers, covered by insurance and understood by both patients and doctors as a safe and effective treatment when used at the right dose with the right precautions.

Krystal, the Yale doctor, said two reasons that ketamine isn’t more common have more to do with process than benefit. Mainstream mental health providers aren’t set up to deliver procedure-based treatments in their facilities, and the field of psychiatry is slow to change.

I’ll add that there is little incentive for pharmaceutical companies to embrace a drug that is cheap and quick to work when antidepressants, which people are sometimes on for years, are a lucrative and growing market.

Despite the hurdles, Krystal said he thinks ketamine and esketamine “will become a bread-and-butter treatment for depression” in the not-too-distant future because these drugs are “the most effective medication that we have” for fighting serious depression.

For my person, ketamine wasn’t a magic bullet. But it is helping. The first time they did it, I stayed with them in the treatment room, along with the medical provider. About a half-hour in, my loved one did something that they had barely done this year.

They laughed, with joy and abandon. A sound like a child on a swing, feeling the rush of summer air.

“This is the real me,” they said.

I cried while they giggled because depression isn’t a solitary endeavor, no matter how it feels. Watching my person suffer has ruled my year, leaving me with deep anxiety every moment that this would be the day they gave up.

In the days afterward, there was a noticeable difference, a calmness and a greater ability to interact with the world.

Not a cure, but a step.

It’s heartbreaking that ketamine, which Perry sought out for help, ultimately led to his death. But Perry was clear that he believed that recovery from both depression and addiction were possible — if not for himself, then for others. I didn’t know him, I don’t speak for him, but I believe he would not want his death to keep others from seeking the help that is right for them.

And he wouldn’t want a scientifically backed treatment to be shunned because it is associated with his death.

Any drug can be abused. But ketamine is one that should be available — and understood — for those, such as my lovely, loved person, whose brains have tricked them into believing that sadness is the best life has to offer.

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 988. The first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Or text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.