Season upon season, watermelons, carrots and corn have sprouted from Daniel Rudnick’s 255-acre farm along Interstate 5 in Buttonwillow, Calif.

Now, the ground lies unplanted. In the next year, it will be cleared and graded to build a 4-million-square-foot warehouse complex.

“Our plan all along was that we were going to leverage the value of this huge trade route ... and its location to do something more than just grow field crops,” Rudnick said.

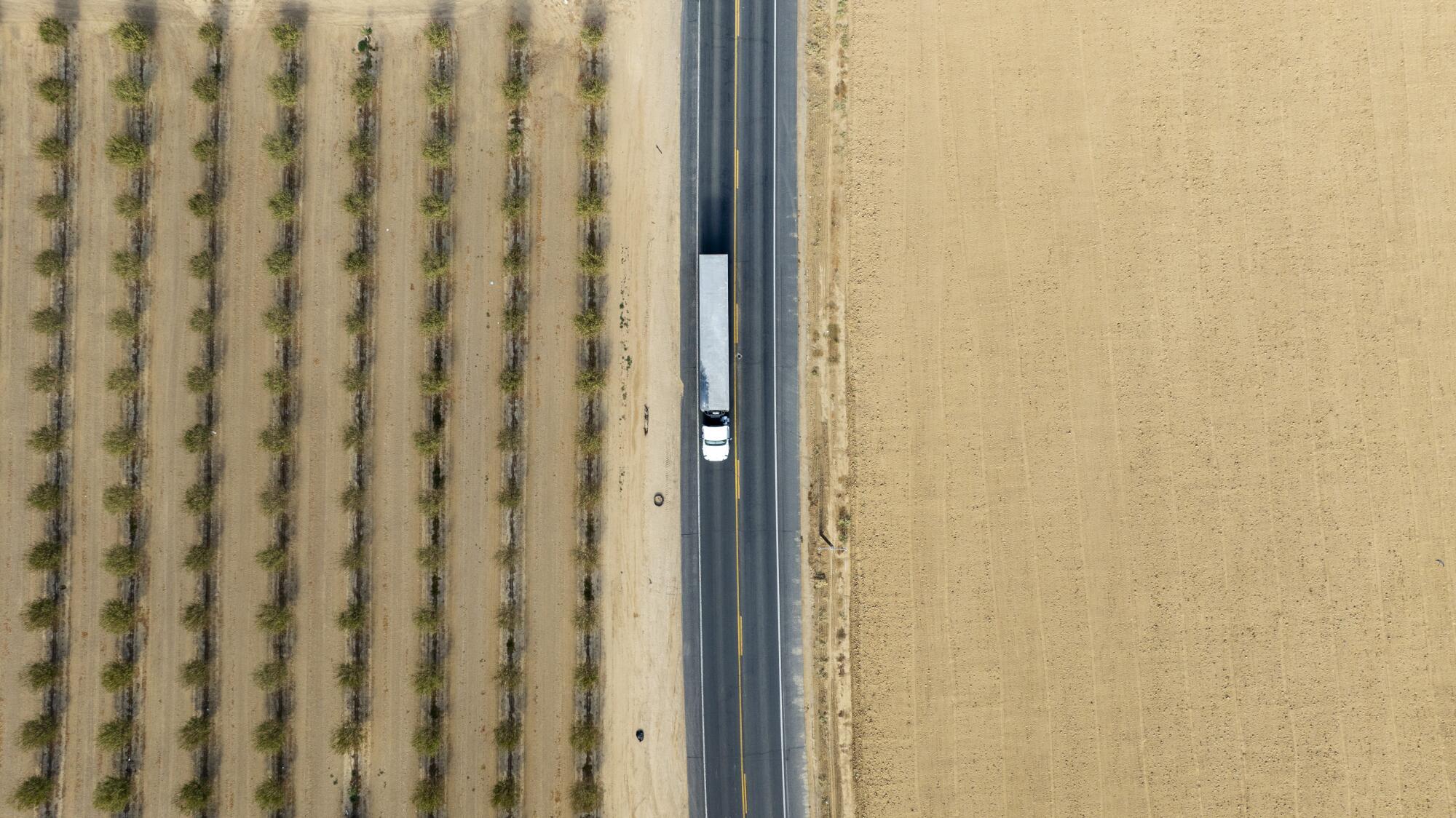

Similar transformations are happening across Kern County, the southern gateway to the San Joaquin Valley, which is poised to become the next frontier for Southern California’s warehouse industry, valued at hundreds of billions of dollars.

Farmland once heralded for its high-quality soil is now being eyed for its location in the heart of the state, near major highways. Land owners like Rudnick, frustrated by new state laws that will severely limit access to groundwater, are selling or converting their properties.

Land is being rezoned for industrial use, and massive warehouses are being built on speculation near traditional farming communities like Buttonwillow and Shafter, so goods coming through the Southern California ports can be shipped quickly throughout the western United States.

Unlike the Inland Empire, where warehouses have moved in at tremendous cost to densely packed neighborhoods, the valley offers open space, cheap land and workers eager to exchange backbreaking farm labor for a different kind of toil, indoors.

In Kern County, where the oil industry — the other pillar of the local economy, besides agriculture — will be decimated as the state moves away from fossil fuels, there has not been a groundswell of organized opposition to the warehouses.

“One million-square-foot facilities are the future,” said Herb Grabell, an Irvine-based industrial land real estate advisor and senior vice president for Kidder Mathews. “Kern County, if planned correctly, is unlimited.”

The new warehouses will bring jobs to a region with high unemployment, but some question whether workers will be better off with low-wage warehouse jobs. The environmental effects of many more trucks, in an area with some of the most polluted air in the country, could be serious.

And some farmers want Kern County to remain just the way it is — the southern end of the most agriculturally productive region in the world.

Daniel Palla, who is Rudnick’s neighbor, fears that a warehouse across the street from his almond farm will bring trucks and cars that won’t know how to share the roads with slow-moving tractors.

As he pulled an almond off a tree and snacked on it, he said he would prefer to see farmland preserved for growing healthy food.

“I believe everybody needs a job, and warehouse space is important,” said Palla, a fifth-generation farmer. “I would rather not take agricultural land to do that.”

A node of warehouses has existed in Kern County since the early 2000s, with Ikea, Caterpillar, Famous Footwear, L’Oreal and Dollar General moving into the Tejon Ranch Commerce Center along the Grapevine on Interstate 5.

The Wonderful Co., of pistachio fame, operates a 1,600-acre industrial park in Shafter, about 20 miles northwest of Bakersfield. The park — built on land where Wonderful owners Stewart and Lynda Resnick once grew almonds — now has 23 tenants, including Target, Walmart, Ross Dress for Less and American Tire.

Another warehouse hub is developing near Bakersfield’s Meadows Field Airport. A 2.6 million-square-foot Amazon Fulfillment Center opened there in 2020, and a 73,000-square-foot warehouse built on speculation is under construction nearby.

The number of warehouse jobs in the county increased more than fivefold between 2009 and 2019, according to a report by the UC Merced Community and Labor Center. Today, there are more than 22,000 jobs in warehousing, transportation and utilities in Kern County, according to data from the state Employment Development Department.

What’s new are the state water regulations, passed a decade ago, that are now forcing farmers to make tough decisions about their properties. At the same time, the Inland Empire is maxing out on available land, following the pandemic-era explosion of e-commerce, prompting warehouse investors to look elsewhere.

“Now, we’re getting speculative development, which is really the highest level,” said John Ritchie, senior vice president of ASU Commercial in Bakersfield. “This is somebody risking hundreds of millions of dollars on a building, saying, ‘OK, we’re going to attract nationwide tenants.’ ”

Kern County officials say that most warehouses will not be close to homes. The county is regulating environmental impacts, requiring that companies take steps to reduce air pollution, said Lorelei Oviatt, director of the county’s Planning and Natural Resources Department.

“It should not be next door to where people live, which is one of the trends in Southern California that has people very upset,” Oviatt said. “Who wants to look out their back door at 4 in the morning and have to listen to a diesel truck spewing into their backyard?”

“Here, we have enough land that we do not have to do that,” she added.

Compared with the Inland Empire, where more than 60 organizations have called on Gov. Gavin Newsom to declare a regional warehouse moratorium, the response in Kern County has been muted so far.

Last year, in one instance where opposition did emerge, local advocates and several residents fought a project that would include a million-square-foot warehouse on a 91-acre site in south Bakersfield, citing health and environmental concerns.

“We have very high asthma rates, not just in the Central Valley, but in that area specifically. We already have a very high traffic of trucks coming into other distribution centers,” resident Nataly Santamaria, with Vision y Compromiso, an organization that supports community health workers, told the city council. “This does not represent what the community wants and what they have been asking for.”

The city council unanimously approved the project, with council member Chris Parlier, who represented the area, noting that the roughly 1,500 jobs associated with the warehouse and an adjacent commercial development “outweigh so many things.”

Gustavo Aguirre, an environmental justice advocate and assistant director of the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment in Delano, is concerned that warehouses will make the area’s poor air quality — fed in part by emissions from cars and trucks, as well as the oil, agriculture and dairy industries — even worse. He said that community members haven’t marshaled against the warehouses because the impacts aren’t yet visible.

“Going from being very dependent on oil to being very dependent on distribution centers is only changing the name of the problem we have here,” he said.

To woo warehouse investors, some Kern County officials are touting the area’s workforce, which includes agricultural and oil workers looking to switch to an up-and-coming field.

Just 19% of county residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and warehouses can provide low-skilled workers with decent wages and benefits, said Melinda Brown, vice president of business development for the Kern Economic Development Council.

But in 2019, nearly four in 10 county warehouse workers made less than a living wage, or the amount necessary to avoid chronic and severe housing and food insecurity, according to an analysis by the UC Merced Community and Labor Center.

Some workers who have experienced the on-off cycles of agriculture say they prefer the consistency of a warehouse job — even if the pay and working conditions aren’t great.

Jose Ojeda, an immigrant from Puebla, Mexico, worked at a Japanese restaurant in the Los Angeles area for 30 years, until it closed during the pandemic.

He and his wife had already moved to Arvin, near Bakersfield, where they could afford to buy a home. He started harvesting and pruning grapes, making $400 to $500 a week. But “sometimes it rains and you don’t work one or two days,” he said.

Then, he found a job at a Dollar General warehouse at Tejon Ranch.

Hired though a company that provides labor to local businesses, he started out making $15 an hour. During the summer, he was bathed in sweat as he unloaded trailers, which felt as hot as ovens. He spent a month at home recuperating from an on-the-job accident.

He quit the job to care for his ailing mother in Mexico. He’s now back in Arvin and working seasonally in the fields, withstanding extreme heat and pesticide exposure. The father of four — three still live at home — is making $15.50 an hour, hardly enough to get by.

He wants a job that’s permanent and not seasonal, so he is applying for forklift jobs at warehouses, hoping to make $20 to $25 an hour. His long-term goal is to open a Japanese restaurant with his wife, who works at a school.

“A job is a beautiful thing because you have the opportunity to learn,” said Ojeda, 48. “But in the fields, you don’t learn more than how to pick and prune grapes ... In a warehouse, you can always aspire to more.”

Maria Espinoza, who lives a few miles from Rudnick’s property, also welcomes the new warehouse jobs. Most of the 1,100 or so people in Buttonwillow are farm workers, she said, with some neighbors employed at distribution centers about 20 miles away.

Espinoza sorted and packed nuts until the birth of her fifth child. The girl is now 4, and Espinoza is ready to work again, perhaps picking up a night shift at a warehouse. It would be more consistent than working in the fields, as her husband does, she said.

“If it rains in the fields, you can’t work,” Espinoza said, “and at the warehouses, you can.”

Juan de Lara, associate professor of American studies and ethnicity at USC, is among those who wonder whether low-wage farm workers will benefit from the warehouse economy.

The challenge, he said, is figuring out how those workers can “access the actual high-skilled jobs within the logistics industry that actually pay a lot more money.”

Some schools are trying to prepare students for those jobs.

On a recent afternoon, high school senior Marc Herrera demonstrated how to use a robotic palletizer at the Career Technical Education Center, run by the Kern High School District. He had recently toured the local Amazon fulfillment center and saw workers there using a giant version to efficiently stack goods onto a pallet.

Herrera, 17, is already earning college credits through the high school’s robotics engineering program and plans to pursue a bachelor’s degree in industrial automation at Bakersfield College. Salaries in the field start at around $70,000, according to Anthony Cordova, the college’s dean of instruction for industrial technology and transportation.

The Career Technical Education Center also offers a logistics and distribution program, which prepares students to get entry-level jobs at local warehouses and move up the ladder, said Principal Brian Miller.

“If you come in with a work ethic and background, like a lot of these kids will,” Miller said, “there is tremendous opportunity to get into the supervisory ranks, the management ranks, where you’re going to be making six-figures, pretty quickly, which is a really good job for our area.”

Training programs like these will help build “a school to Amazon pipeline,” Kern County Supervisor Leticia Perez said.

“My constituents care about almost entirely one thing,” Perez said. “Jobs, jobs, jobs and higher-paid jobs.”

At his farm in Buttonwillow, Rudnick said his family always planned to develop the land, which is bordered by freeway ramps. At one point, they considered building a music festival venue. Under state law, the farm would have access to two-thirds less water by 2040, said Rudnick, who will retain an ownership interest in the land and the buildings.

At a meeting in September, just before Kern County supervisors unanimously approved the project, union representatives expressed support.

Along with almond farmer Palla, another Rudnick neighbor raised concerns about the impact on his daily farming operations. Aguirre, the environmental justice advocate, questioned how warehouse developers can help improve local communities.

Three of the warehouses planned for the property will support e-commerce. A fourth will be a cold-storage facility. The idea, Rudnick said, is to start building even before tenants have signed leases. Also included will be a 21-acre solar energy microgrid as well as wastewater and water treatment facilities. The project will use 89% less groundwater than the farm did, according to Rudnick, and will provide 200 full-time construction jobs and up to 2,000 permanent jobs.

Rudnick has also agreed to pay the county $300,000 a year to fund a paramedic for the Buttonwillow area.

“We have an obligation to do something beneficial and productive with our land,” Rudnick said.

This article is part of The Times’ equity reporting initiative, focusing on the challenges facing low-income workers and efforts being made to address the economic divide in California. More information about the initiative and its funder, the James Irvine Foundation, can be found here.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.