After a year in office, L.A. County sheriff talks deputy gangs, jail deaths, overdoses

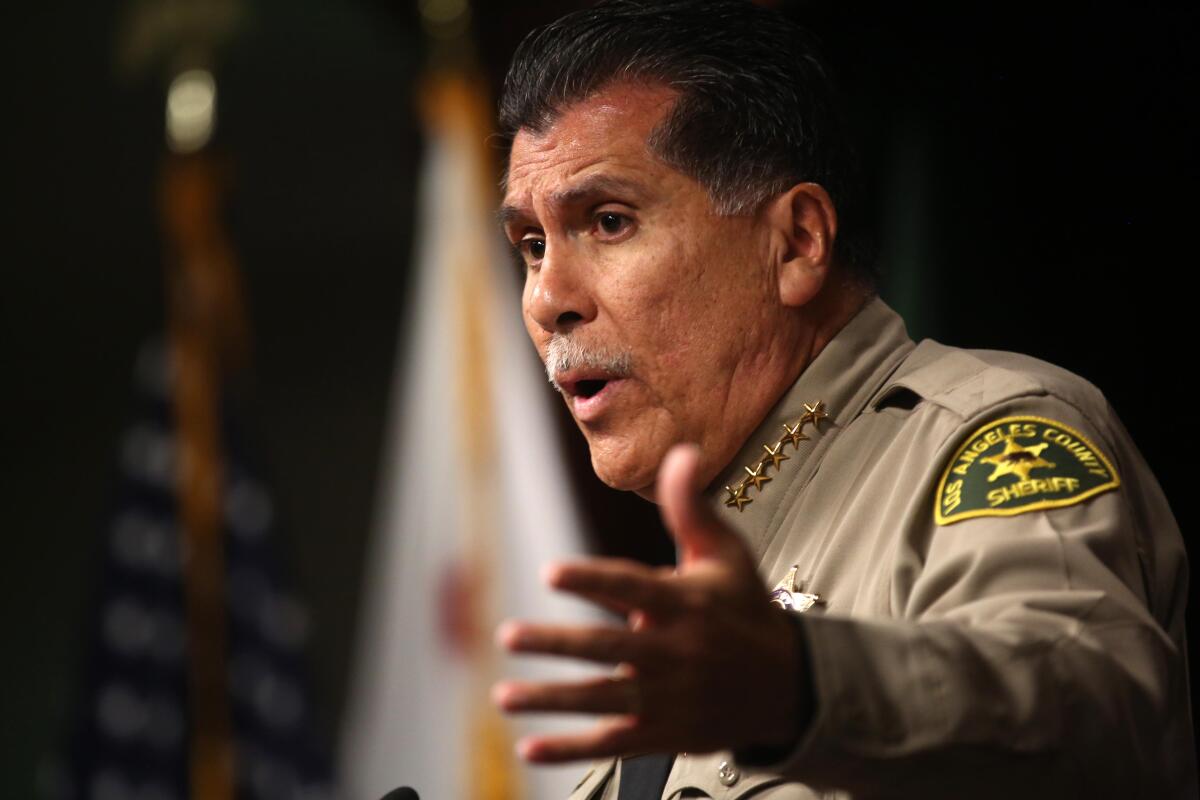

By the time Sheriff Robert Luna ousted his predecessor and became L.A. County’s top cop in late 2022, the nation’s largest sheriff’s department was awash in controversy.

The half-century-old problem of deputy gangs had brought the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department under increasing national scrutiny. Jail conditions were becoming increasingly dire, and the decades-old lawsuits about them seemed no closer to resolution. On top of that, the department was short on staff, mired in scandal and often at odds with county leaders.

A year later, many of those problems remain unresolved — and critics say the new sheriff has little to show for his time in office. The department has yet to ban deputy gang tattoos, and the courts have stymied efforts to identify the gangs’ alleged members. County data show roughly 20% of sworn positions are effectively vacant, jail death rates are soaring and, in June, the county only narrowly avoided a contempt hearing over conditions inside its lockups.

Still, the signs of change are unmistakable. After taking office, Luna quickly opened up more access to oversight officials. He created the Office of Constitutional Policing to help the county comply with four federal consent decrees, eradicate gangs and overhaul policies that could help reform the department.

So far this year, deputy-involved shootings are down, and the jail population is falling. Deputies are using force against inmates less frequently, and the department created a timer system to make sure jailers stopped chaining mentally ill people to benches for days. And this week, in an interview at the Hall of Justice, Luna told The Times he’s formulating a plan to close the county’s oldest lockup.

“Men’s Central Jail needs to be replaced,” he said. “We need something that resembles a care campus that can deal with what custody should look like toward the future.”

Exactly how that would work is still fuzzy, and the sheriff would only promise more details in the future, hinting at something perhaps loosely inspired by the gentler prison systems of European countries. Making that a reality will be an uphill battle — just like some of the other lofty goals Luna has in mind.

“For a sheriff’s department or a police department to be successful, we need to be properly led and properly partnered, staffed, equipped and trained,” he said. “I was handed a department that has been deficient. ... And we have a lot of work to do. A lot of work.”

Over a little more than an hour, Luna explained what some pieces of that work could entail. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

*****

One of the issues that was pretty central in your campaign was eradicating deputy gangs. A year later, there’s still not a strong anti-gang policy in place. Why is that?

During the campaign I talked about deputy gangs. I raised my hand and said, “We have a problem.” So I’m admitting there’s an issue. That’s why we started the Office of Constitutional Policing. But remember this: any time we’re dealing with employees’ hours, working conditions or things that impact people’s daily lives, we have to go through a meet-and-confer process. When we started to draft the policy — although the Civilian Oversight Commission gave us their version of it — we still had to go through it and make sure that it was something that could work.

A special counsel report found that at least half a dozen “gangs” or “cliques” of tattooed deputies are still active in the Sheriff’s Department, including the Regulators, Spartans, Gladiators, Cowboys and Reapers.

So [Office of Constitutional Policing director] Eileen Decker not only had to go through the Civilian Oversight Commission and the Office of Inspector General, but also the federal monitors. Once that was done, there were unofficial conversations going on with the different labor organizations. And then, I want to say sometime in October-ish, we gave it to them in a formal manner. That’s when it becomes official.

This problem has existed for 50 years. I’ve been in office now for a year. I want to fix this. That is my goal. Yes, it is taking a little bit longer than I would like to see, but our labor organizations have been good partners at the table. We don’t agree on everything, but I think we’re going to get to a good place.

Do you think you’ll have a new anti-gang policy in place at some point in this next year, during your second year in office?

That is my absolute expectation.

There was a widely criticized incident in Palmdale, where a deputy punched a woman with an infant in her arms. Can you tell me anything about if you’re making changes to policies about when deputies can punch civilians?

It’s still being worked out. But from my perspective, if one of my deputies is getting his butt kicked and it’s a fisticuffs, you have a right to defend yourself. And if you have to use personal weapons — punching somebody in the face — to do that, then you have to defend yourself. I would not take that very valuable tool away from our employees.

But if you have a suspect who is not fighting you but only resisting, that’s where I draw the line and say that you don’t just start punching people. I get it, sometimes it’s very difficult to handcuff people. And historically that has been allowed here and that’s what is catching a lot of employees off guard. The miscommunication is [they think], “Oh, he just wants to take it away from us.” No, there’s a time and place for it. Because when you’re using force on an individual, it’s to gain control, not to punish. There’s a difference there.

Was the incident in Palmdale what prompted you to evaluate the policies about punching people?

It was one of many things. We’ve had several incidents over the last year where personal weapons were used to overcome resistance, not in a fight.

According to a recent letter sent from the American Civil Liberties Union to the Board of Supervisors, the Sheriff’s Department has been finding uses of force against jail inmates to be within policy more than 98% of the time. But the federal court-appointed monitors agree only about two-thirds of the time. How do you explain that discrepancy?

I was told about that ACLU report probably about three or four hours ago. We’re making inquiries about if there is actually a discrepancy. But there are definitely challenges. When we’re talking about use of force, the federal monitors have said they don’t like the fact that they believe that our front-line supervisors are not holding employees accountable. So we are currently looking at that.

But as I’m talking to all of our supervisors, I’m talking about accountability. We have to be courageous and identify challenges that we’re having because that negatively impacts public trust and credibility. And honestly, it’s hanging our employees out to dry. Because if you’re not taking corrective actions or showing people that this is wrong, then other employees won’t believe it’s wrong.

A lot of the employees that I talk to when I visit stations, they’re frustrated with me because there’s been instances where people have been disciplined and they believe that you’re holding us to this standard, but yet you’re not providing the required training to get us there. So I’m doing an evaluation on our training — but I don’t need an evaluation to tell me we’re deficient.

One of the other issues with the jails has been the high death toll. As of today, the jails are a couple deaths away from having the highest death rate in at least 15 years. Why do you think that is?

Every time I see a notification that somebody dies in our custody, it’s like, “What the heck?” You don’t want to see any. I don’t want anything to go wrong while they’re in our custody.

I think there is a perception that people who are dying in our custody are dying due to force incidents or murders. Now, once in a while you will get somebody who does get murdered in our facility. This last year we attributed nine deaths to overdoses. And there are nine other autopsies that are still pending, but a lot of these cases look like they’re from natural causes.

“This is a watershed moment for the ACLU’s jail and prison decarceration movement,” Corene Kendrick, deputy director, ACLU National Prison Project, said.

A lot of the people that we take into custody, they’re probably getting the best healthcare they may have ever received in their entire life while they’re with us, which means that rarely does somebody go see a doctor. Then when they get to us, you get people who are ill, fall ill and then they end up dying in our custody. So if I have nine overdoses, how do I reduce those?

Some facilities have tried to minimize opioid overdoses by expanding access to medication-assisted treatment that reduces the urge to get high. Historically, this is something that your department has not broadly used. Do you have any plans to expand that?

I want to dig a little deeper. If there is resistance, is it from our department? Is it from Correctional Health Services? Is there a reason? I’d like to know. We have already gotten more canines to do drug detection. We need better body scanners. We’re working through our CFO to try and figure out how we can do that. We believe that a lot of the drugs are coming in through mail.

I envision — and I’m already working on this — all of our custody facilities getting really good internet service so that I can get tablets in and eliminate mail. Can you imagine if I can give a family the ability to FaceTime, what that would do? There’s so many opportunities.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.