What day laborers are hired to do: the dangerous, the gross, the sometimes illegal

They were not what you’d call the usual day laborer gigs.

No yard work. No installing doors. No laying down roof tiles on a hot summer day.

There was the person who paid several workers to stand in line for concert tickets. The one who wanted to hire a few men to just sit around with him, drink and watch some porn. And then there was the company that contracted day laborers to clean a former brothel, complete with a stripper pole, used needles and the scent of dead body.

These stories, recounted by laborers and organizers in Los Angeles County in recent days, don’t come close to the experience of four workers recently hired to dump trash bags picked up in Tarzana. First they were told the bags contained rocks. Then Halloween decorations. They quickly realized the heavy, squishy bags were filled with dismembered body parts.

LAPD chief confirms inquiry into whether officers ignored a report that a suspected killer tried to get workers to remove bags of remains from his Tarzana home.

As long as men and women in difficult straits have waited for work on street corners and outside home improvement stores, some have inevitably been hired to perform questionable, exploitative or just plain weird tasks.

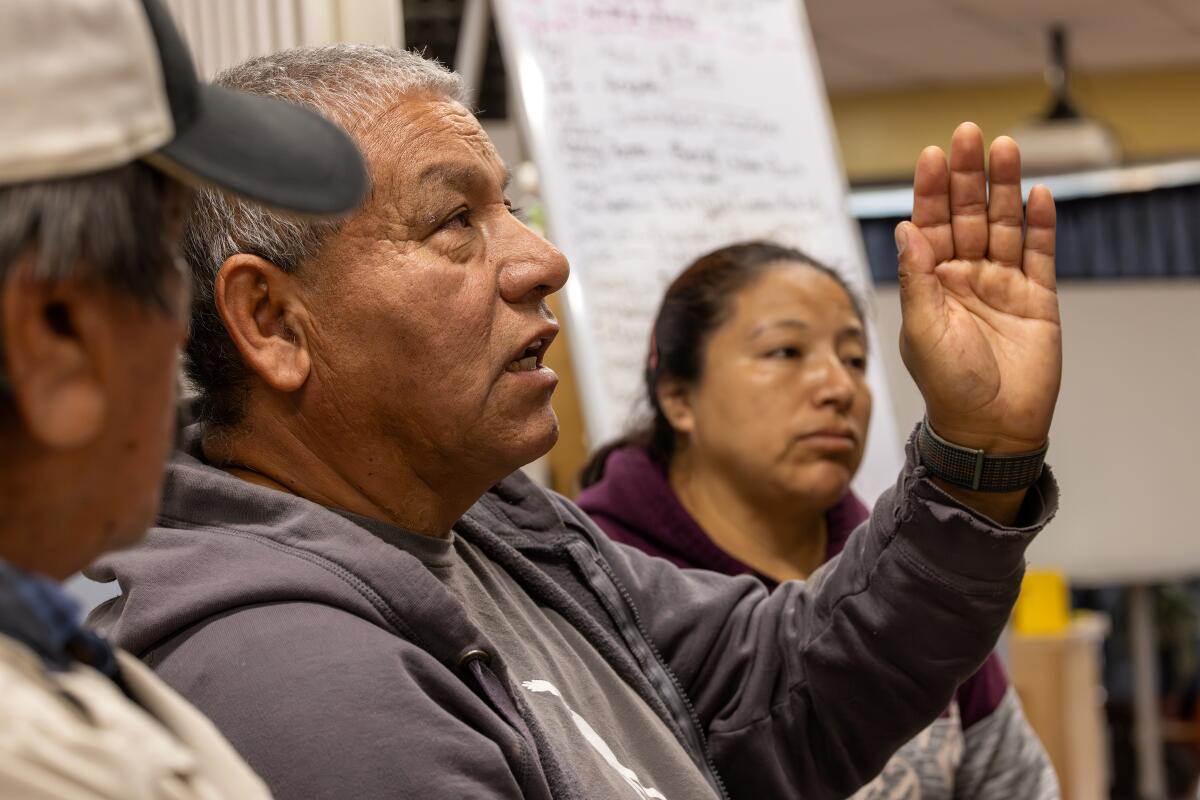

“We know that all of us run the same risk,” said Cesar Beiza, 59, who has worked as a day laborer for seven years. “When we go out to work we don’t know what we’re exposing ourselves to.”

On a recent weekday morning, as the sun began to tinge the sky blue, about a dozen day laborers gathered at the Pasadena Community Job Center.

The men — in blue jeans and paint-spattered work boots — sipped Winchell’s coffee as they waited for the raffle that would determine the order in which they’d be offered jobs.

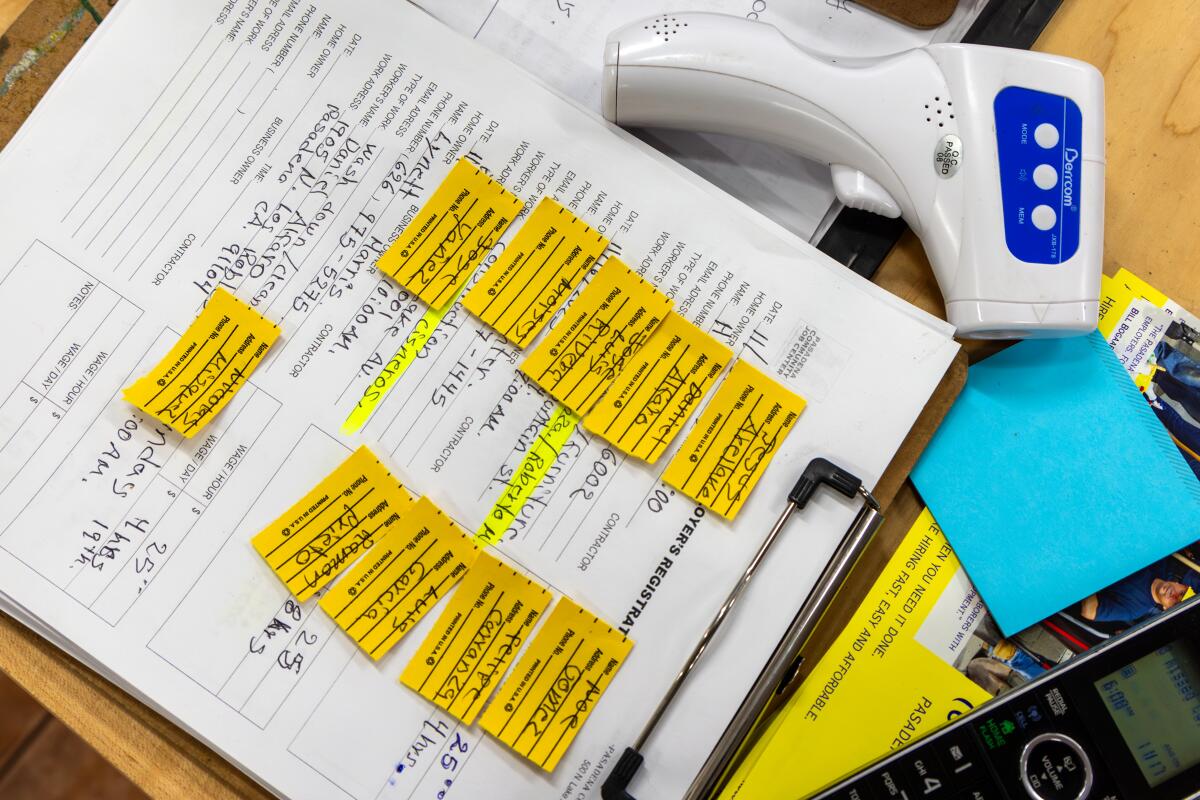

“Rifa, rifa,” Juan Dominguez called out at 6:15 a.m., shaking a can with yellow tickets bearing each worker’s name. Each pull determined the order of the 12 workers there so far.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

When a job came into the center, which is run by the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, the first person on the list would get dibs. Around these months though, work slows down and the jornaleros could wait hours for nothing.

After securing his No. 7 spot, Daniel Alfaro grabbed two cookies and coffee from the center’s kitchen. In his 15 years as a day laborer, he’s gotten most of his jobs through centers such as this one.

Here, like at day labor centers across the country, staff document the names of employers, their contact information and the jobs workers are being hired to do. Some of the most common include yard work, painting, moving and construction.

“It’s always better to be at a center than on the street,” 68-year-old Alfaro said. “Because here, we’re more protected.”

But strange jobs have sometimes come anyway.

Beiza recalled a time several years ago when he and two others were contracted by a demolition and cleaning company to clear out and clean a house in the San Fernando Valley.

The house smelled so strongly of a dead body that “a lot of people might have refused to go inside,” Beiza said. But they needed the $150 they would each make for the day.

“We live from day to day,” Beiza said. “If we work today we will probably not work tomorrow. We have to take advantage of the opportunity, but sometimes we put our lives and our health at risk.”

Once inside the house, Beiza said, it quickly became clear that it was a “casa de citas,” a brothel. There were condoms, pornographic DVDs and syringes strewn around the two-bedroom home. But most worrisome was a room that locked from the outside.

Inside were clothes, shoes and toys that apparently belonged to a little girl.

When they asked the owner what had happened inside the house, Beiza said, she told them she didn’t know and that she had only been renting it out. As Beiza and another worker, Jose Sevilla, moved a sofa outside, a syringe that was inside nearly pierced Sevilla in the neck.

That story ran through Beiza’s mind, after a staff member from the center shared a link to the Tarzana story with workers and warned them to be careful.

On Nov. 7, Samuel Haskell allegedly hired four day laborers to take away several black plastic trash bags, which weighed about 50 pounds each, from his home in Tarzana, according to authorities.

In an interview with NBC4, one of the men said Haskell had tried to pay them $500 to haul away bags he first said were full of rocks, then later said contained Halloween decorations. But the day laborers told NBC4 the contents felt soft and soggy, like meat.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“When we picked up the bags, we could tell they weren’t rocks,” one of the workers said in Spanish.

After initially taking the bags, the men stopped their truck a block away, checked inside and saw dismembered body parts, including a belly button. The men returned the bags and the money and reported it to the police.

That same day, Haskell was allegedly observed and photographed a short distance from his home dumping a large trash bag into a dumpster. The next day, someone looking through that dumpster found a torso in a trash bag and called 911.

Haskell has since been charged with three counts of murder in connection with the disappearance of his wife and in-laws.

Pablo Alvarado, co-executive director of the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, said his group is trying to track down the Tarzana workers in hopes of arranging — if needed — for them to get U Visas, which give immigrant victims of certain crimes the chance to live and work legally in the U.S. if they cooperate with authorities.

“It’s terrible what happened to them,” he said. “Day laborers are subjected to these types of things. Not murder, but very weird job assignments.”

Alvarado recalled serving as an expert witness in a case more than a decade ago, involving workers who were taken from a day laborer corner to care for a marijuana plantation.

They were blindfolded so they wouldn’t know where it was. They remained on the plantation for a long time, until they were caught taking care of the marijuana plants and accused of being the people running the operation, he recalled.

Although no one shared a story quite as alarming as the Tarzana incident, organizers said some workers have been solicited for sex, hired for one thing but then told the employer’s true intentions later.

It’s a case that played out in Phoenix in 2019, when Brenda Acuna-Aguero picked up a worker outside of a Home Depot, telling him she and her husband needed help moving some items in their house.

When they got to her home she began “to talk sexual to him and stated that it was her fantasy to have sex with a laborer and that she wanted to have sex with him,” according to court documents.

After the victim refused, the woman’s husband, Jorge Murrieta-Valenzuela, forced him to have sex with her at gunpoint, the victim told police. The couple was arrested soon after.

They received a five-year prison sentence for sexual assault.

More than a dozen men waited for work outside of a Home Depot in Monrovia on a recent morning. Everth Figueroa, 43, was one of the few who hadn’t heard the grisly news. Figueroa has been coming to this spot for the last three months, ever since his former boss got too sick to continue his landscaping business.

By 11 a.m., only two or three jobs had come in. With so many men waiting for work, it sometimes came down to suerte, luck. Figueroa, sunburned from hours outside, had been waiting since 7:30 a.m. and hadn’t yet gotten lucky.

“The jobs that we do, usually, are jobs that most people don’t want to do,” Figueroa said.

The majority of his employers, who have hired him for painting, roofing and demolition work, have been good people, he said. But about a month ago, a woman instructed him to cut plants he later realized were toxic. He was given no protective gear.

After six hours of work, the woman said he’d cut the wrong plants and she’d only pay him for two hours of work — $40. Afterward, Figueroa was sick for a week with chills and hives.

“I wish they’d at least paid me, because then at least it would have been worth it to get sick,” he said, with a tight smile.

About a month ago, Rutilio Portillo and another worker had been hired to paint a porch. The men worked for six hours, before one of the employers pointed out a paint droplet that had fallen on the window.

The employer refused to pay them.

“They let us work the entire day until we were almost done and that’s when they came up with an excuse,” 63-year-old Portillo said.

The issue of wage theft comes up most often for day laborers, according to Maegan Ortiz, executive director of the Institute of Popular Education of Southern California, or IDEPSCA. The organization operates five centers for day laborers.

Recently, Ortiz recounted, a teenager completed a tiling job and didn’t get paid. In September, IDEPSCA staff documented $73,683.77 in stolen wages at its centers.

The organization supports workers either by doing mediation directly with the employer or filing a state, city or county wage claim for them.

“Wage theft continues to be the number one issue,” Ortiz said. “Workers being underpaid, not paid, not paid overtime.”

Ortiz said she wasn’t surprised to hear the case out of Tarzana, although she said it’s “the first time we’ve heard of such explicit, illegal activity and making workers complicit.”

She cited an “assumption by general society that workers can and should do anything and any type of work” and that “because of their assumed undocumented status” they won’t speak up.

In the Tarzana case, the workers first went to a nearby state Highway Patrol office. There they were directed to the Los Angeles Police Department’s Topanga area station with “a report of concerns relative to the contents of some trash bags that they had been asked to dispose of,” according to LAPD Chief Michel Moore.

The officer at the station desk did not speak Spanish and couldn’t understand the day laborers’ story, according to police sources who requested anonymity to discuss the ongoing investigation. The officer then summoned a Spanish-speaking officer who told the workers to call 911.

“This demonstrates and reinforces the idea that the police are not there to help our community,” Ortiz said. “Because even when there was something so obvious and the workers did ‘the right thing,’ police didn’t respond.”

Moore said the department has launched an internal investigation into the matter.

To the day laborers who heard the story, it felt like another indignity in a vocation that’s full of them.

“They went to the police and they didn’t listen to them,” said Beiza, who was hired to clean the brothel. “We’re day laborers, we’re Hispanic and they treat us like we don’t have value to report situations like that.”

In his mind, the officers probably thought the workers were lying.

“They had to go various times to make this report before they were listened to,” Beiza said. “If another day laborer hears that and finds themselves in a similar situation, what are they going to think?”

Times staff writer Richard Winton contributed to this report.

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.