Column: What a refusal to study turning a freeway into housing says about L.A.’s future

Until a few days ago, Michael Schneider truly believed that his nonprofit, Streets For All, had solid enough political support to pursue what was certain to be an unpopular idea in L.A.: a study of whether it makes sense to rip up a Westside freeway and replace it with affordable housing and a humongous park.

He was a man about town, excitedly touting the letters and statements of “immense enthusiasm” from elected officials.

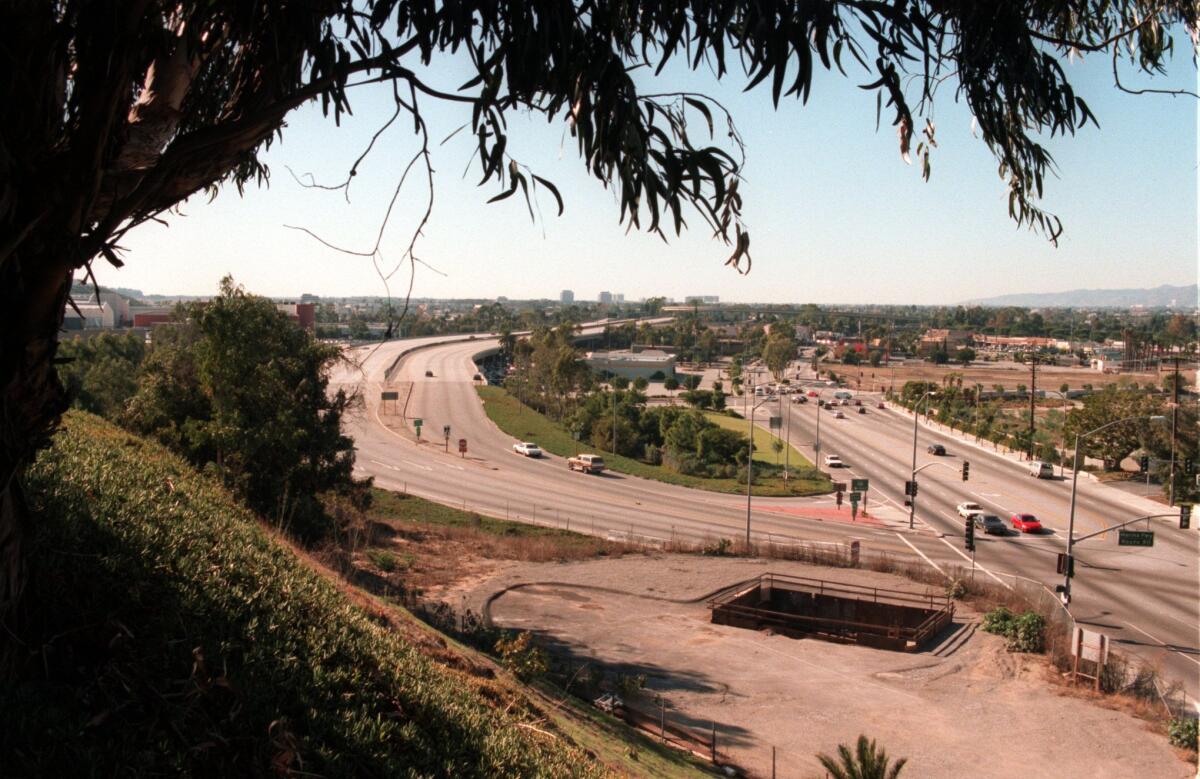

Like from the office of Mayor Karen Bass, who called the Marina Freeway — a three-mile, lightly trafficked stretch of Route 90 that was left unfinished after a plan to link it to Orange County was abandoned in the 1970s — a “freeway to nowhere.”

And from state Sen. Lola Smallwood-Cuevas (D-Los Angeles), who described Schneider’s idea as “a forward-thinking project that would help alleviate L.A.’s need[s].”

A transportation advocacy group wants to turn the three-mile stretch of the unfinished Marina Freeway in Culver City into public parks and thousands of affordable housing units. The idea has already garnered some support.

Indeed, as someone who drives the Marina Freeway all the time, I’ve long thought there had to be a higher and better use for the land than a mere shortcut from Marina del Rey to the 405 Freeway and over to South L.A. And so I was excited to hear that Streets For All was applying for a federal grant to study it for two years, tracking everything from environmental impacts to traffic to the opinions of nearby residents like me.

Now, though, my excitement as well as Schneider’s has given way to familiar feelings of frustration. True to form for NIMBY-indulging Los Angeles, the political support he believed was solid has suddenly turned porous.

That includes Bass: “I do not support the removal or demolition of the 90 Freeway,” she said in a statement last week. “I’ve heard loud and clear from communities who would be impacted and I do not support a study on this initiative.”

L.A. City Councilmember Traci Park agrees with her. After conducting a very unscientific poll of her Westside constituents, she wrote in her newsletter that: “The 11th District does not support the demolition of the 90 Freeway. Your voice is why Mayor Bass rescinded her initial support.”

L.A. County Supervisor Holly Mitchell told me that, despite rumors to the contrary, she never decided to back a study or tearing down the Marina Freeway, which abuts her district in the unincorporated neighborhood of Ladera Heights. “But it’s a moot point now,” she said.

Meanwhile, Smallwood-Cuevas said she still supports a feasibility study, but cautioned this week that it can’t be at “the expense of transparent community-driven input and analysis.”

Similarly, Assemblymember Isaac Bryan (D-Los Angeles) said he’s never opposed to research. But there’s a difference between studying the impact of removing the freeway and, referring to several renderings of what Schneider envisions as Marina Central Park, “proposing an alternative design and resolution without a study having been completed.”

“The 90 Freeway,” Bryan assured me, “is not going anywhere.”

It’s problematic that, at a time when roughly 75,000 people are sleeping in the streets countywide and vehicle emissions are exacerbating the effects of climate change, Los Angeles can’t summon the unified political will even to study — STUDY! — whether to replace a freeway with housing.

Equally problematic is the reason why.

I’m not talking about the blame that some have placed on Streets For All for being overzealous with its messaging and tactics. Or that, according to others, elected officials were too quick to surrender to the fears of their constituents, some of whom wrongly believe the removal of the Marina Freeway is imminent.

I’m talking about the fundamental disagreement in Los Angeles over the role and importance of community outreach. How much of it is enough? How soon should it be done? How much weight should it be given? And to what end?

These unanswered questions are ultimately why political support crumbled for studying the Marina Freeway, and it’s a troubling harbinger.

Most residents understandably want a say — or the say — in what happens to their neighborhood, whether it’s affordable housing on what’s now a freeway or a homeless shelter on what’s now a parking lot.

But given the size of the unhoused population and the scale of the housing construction needed to address it and lower rental prices for everyone else, I increasingly believe L.A.’s political leaders can’t keep putting so much stock in the opinions of residents. Not all development projects that are worthwhile or necessary will be popular.

“For so long, the loudest voices have usually derailed things,” Schneider said. “And all I’m saying is the loudest voices aren’t always the most correct voices.”

::

People don’t like change.

This is a truism that has led NIMBYs to file an untold number of frivolous lawsuits up and down the state of California.

It also has led Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature to repeatedly roll back local control over land use decisions — the latest being a law that lets nonprofit colleges and religious institutions bypass most local permitting and environmental review rules and rezone their land to build housing.

Even Bass, who has made homelessness her top issue, has pushed to cut through red tape and streamline the construction of housing and shelters, trying to extend the pipeline for unhoused Angelenos who have been moved into hotels through her Inside Safe program.

But the mayor said she’s still a big believer in “doing the hard work” of community outreach. She explained why when I shared my skepticism.

“This goes back to my days at Community Coalition,” she said. “We used to fight when the city tried to impose development on South L.A. without including South L.A., which is why you would think that I would say build everywhere, anywhere. But I don’t feel that way.”

Instead, she wants to get people involved in the process and build in ways that are in line with what each community wants.

“If I took a position that said, ‘steamroll everybody, just get housing done,’ we would tear the city apart,” Bass said, adding that residents would likely be against development for no reason other than it was forced upon them.

Twenty years after its first run, ArroyoFest will again shut down a stretch of the 110 Freeway between Los Angeles and Pasadena for a car-free celebration.

This is a big reason why she decided against supporting a study of the Marina Freeway. In talking to residents, she told me she heard only complaints — about the possibility of more traffic and longer commutes, and from Black people in South L.A., about losing a convenient corridor to Marina del Rey and the beach.

But most of all, Bass said she heard consternation that there had been no community outreach.

This came up in an online petition that went viral last month — even though it was packed with misleading assertions — written by Daphne Bradford, an education consultant from Ladera Heights who is running for supervisor against Mitchell in the March primary election.

“Ladera Heights is not just any neighborhood; it holds the distinction of being the 3rd most affluent African American community in the nation,” Bradford wrote, channeling her inner NIMBY. “Our community has worked hard to create a safe and prosperous environment for our families, and we believe that our voices should be heard when decisions are made that will affect us directly.”

Schneider sighed when I asked him about the petition.

“The whole point of the feasibility study is we would have almost two years of community outreach,” he said. “We’re a small nonprofit, we don’t have the resources to do the community outreach before getting the grant money.”

In the meantime, rumors about the Marina Freeway have overwhelmed the facts, and many residents have dug in their heels in opposition to whatever they think is happening. Mitchell suspects one reason for this is that Streets For All didn’t “do outreach the way we define outreach.”

“It can’t be 10 a.m. on a weekday, one meeting at the community center,” she told me. “You really have to get creative, partner with communities and not be afraid to reach out to people who will oppose you.”

But community outreach is a thorny issue, Mitchell acknowledges. Again, people don’t like change. And too many people want to “pull the drawbridge up” behind themselves and not let new housing into their neighborhoods.

“When people say outreach, they mean, ‘You didn’t ask me. And then when you asked me, you didn’t do what I said,’” Mitchell said. “That can’t be the expectation. But I do believe that every effort should be made to make sure that impacted communities are aware.”

Eventually, though, everyone will have to get used to the idea that our neighborhoods will look a little different to accommodate the housing that Los Angeles needs.

“These are really difficult decisions that we all kind of have to make,” Mitchell said.

::

Which brings me back to the Marina Freeway.

Despite Streets For All being abandoned by much of the political establishment in Los Angeles, Schneider said its plan to conduct a feasibility study isn’t dead.

“We live in a democracy. You can’t stop somebody from studying something in the public space. That’s just not possible,” he said. “If we’re awarded the federal grant, we will do it. If we need to raise the money privately, we’ll do it. But we’re committed to exploring the idea because it’s worth exploring.”

Whether that study leads to removing the freeway and building thousands of units of affordable housing in Marina Central Park is another matter.

It’s a huge political decision, Schneider admits. One that will ultimately — undoubtedly and unfortunately — hinge on community outreach. After all, this is L.A.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.