L.A. used to be awash in beauty pageants. Where’d they go?

There she … isn’t.

When was the last time you watched a crown-and-sash pageant? Or even read any news about a Miss-So-and-So beauty queen?

The last I remember were in movies: “Miss Congeniality,” and Holly Hunter’s yearning to become “Miss Firecracker” in her small Southern hometown.

But a live competition for queens of places and queens of industries? Certainly none as magnificently named as Yellville, Ark.’s “Miss Turkey Trot/Miss Drumsticks” pageant, nor Pennsylvania’s Bituminous Coal Queen, and not the recent crowning of Queen Nicotina LXXXVII (the 87th) in southern Maryland’s historic tobacco country.

The Cold War gave us Miss Atomic Bomb — top that, Commies. She was photographed in 1957 after winning her title in Las Vegas, that glow-in-the-desert city within sight of the even more incandescent nuclear testing grounds. She is posing exuberantly, her arms up-flung, with a cloud of blonde hair and, affixed to her swimsuit, a cottony, torso-sized mushroom cloud.

I don’t know how Brooke Robin came to be chosen to be National Uranium Queen, in 1956, but her photo — in fishnet stockings and high heels, posing with pick and shovel — made the papers all over the country. Her reign must have a half-life of 4.5 billion years.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

And only from Life magazine do I know that, on a June day in 1951, right here on Sunset Boulevard near Cahuenga, on the five acres of the Muller Brothers’ full-service gas/repair/tires/Oldsmobile sales empire, a PR stunt arrayed beauty queens across the premises, among them Miss New Car Department, Miss Polish Job, and of course Miss Lube Rack.

Yet like most veteran reporters, I was once assigned to cover one: a California Dairy Princess pageant, where I was told that the title is princess, because “there is only one queen in the dairy business, and that is the cow.”

I can’t say for sure, but I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that over the decades corporate America has crowned Miss Cling Peach, Miss Avocado [Hass and Fuerte], Miss Radial Tires, Miss Dry-Roasted Peanuts, Miss Number Two Pencil, and Miss Brannock Device.

So what’s become of these glamour-fests?

Start at the top, with the waning of Miss America’s profile, from a 1921 Atlantic City beauty “revue” to gin up business after Labor Day, to its glory days, to today.

This coronation of the model American girl was once America’s highest-rated TV show, carried live in prime time to tens of millions on a major network — 85 million in 1960. The 2023 contest was viewable on a pay-to-watch streaming site.

For years, Miss A’s image was preserved so unsullied by real-world controversy that in the mid-1960s, as Frank DeFord wrote in his book “There She Is,” when an interviewer brought up race, the No. 1 national topic of the moment, a pageant official walked the new queen right out of the room. A half-century or so later, in 2017, finalists didn’t dither or demur in answering judges’ questions about the Paris climate accords, the Charlottesville neo-Nazi rally, and Donald Trump’s alleged collusion with Russia. 2023’s Miss A, Grace Stanke, is a nuclear engineering student who’s been speaking at international conferences and promoting nuclear energy as a climate change solution — and doing it in comfy, flat sandals too.

Los Angeles’ first documented smog attack — yes, we had smog attacks — was in 1943. We’ve been fighting the sources of pollution and the quirks of geography that trap it ever since.

For pageants less august than Miss A, I saw in Pageantry Magazine ever more elaborate and overlapping titles: Universal Miss, USA American Miss, Miss Earth USA (committed to environmental projects and climate leadership training), Miss All-Star-United States, Ms. Senior USA, and Miss American Coed (didn’t that word go out with poodle skirts?).

Here, we still have Misses Downey, Antelope Valley, Tustin — at least a dozen or so in L.A. and Orange counties. Most of them are at pains to play down any of the old hubba-hubba stuff and instead affirm their missions of community and service. Santa Clarita calls its crowned competition the Miss Santa Clarita Valley USA Leadership Program.

If you’re not reading about these even in your own neighborhood, it’s partly because the hometown newspapers that used to cover them have been disappearing.

As have some of the pageants themselves. The women’s movement has afforded women more and richer paths for education and careers than via swimsuits and sequins. The Miss America tragic brag that it was the single biggest source of scholarship money for women in the United States always galled me to the gills.

In 1997, in these pages, I let fly: “Take a moment to get your mind around that. The richest pot of dough available to America’s young women to educate themselves to become doctors, CEOs, professors, public officials, lawyers, leaders of nation and family — and you have to parade around in a bathing suit on national TV to get it. Imagine telling a young man he could win a full ride to Pomona or Cornell if he’d sashay down a runway with 49 other young men all dressed like Tom Cruise in ‘Risky Business.’”

Miss America did away with the swimsuit component in 2018, and changed its mission title from “pageant” to “competition.” Its contestants are now “delegates,” and instead of swimsuits, they wear sparkly athletic outfits in the health and fitness event.

The bikini-and-stiletto parades of yore, and the pageant’s practice of sharing contestants’ measurements — which didn’t end until 1986 — reeked of skin-mag salaciousness, not the “health” that organizers supposedly valued.

Mallory Hagan, Miss America 2013, described for A&E’s recent series “Secrets of Miss America” what contestants did to look swimsuitable. “I saw laxatives, I saw caffeine pills, diet pills, things that probably shouldn’t be sold on a market. I saw prescription drug abuse, you name it. I’ve not had water for 24 hours ahead of a swimsuit competition so that I would dehydrate myself to the point of, you could see my muscles, and I’m not the only one.”

Other pageants have followed suit in ditching the suit. For example, next month, Miss Southern California and Miss Long Beach contenders will compete without having to wear either long evening gowns or swimsuits, and the organizers “welcome unusual hair styles/colors, piercings, eyewear, and tattoos.”

(It’s confusing, this universe of similar-sounding titles. The local feeder competitions that send women to the Miss America event are quite different from the strictly-on-looks pageants for Miss USA and Miss Universe, which Trump once owned. Trump told radio shock jock Howard Stern that one reason he bought the franchise was that judges had begun factoring the women’s intelligence and career goals over their looks. “They had a [judge] that was extremely proud that a number of the women had become doctors. And I wasn’t interested.”)

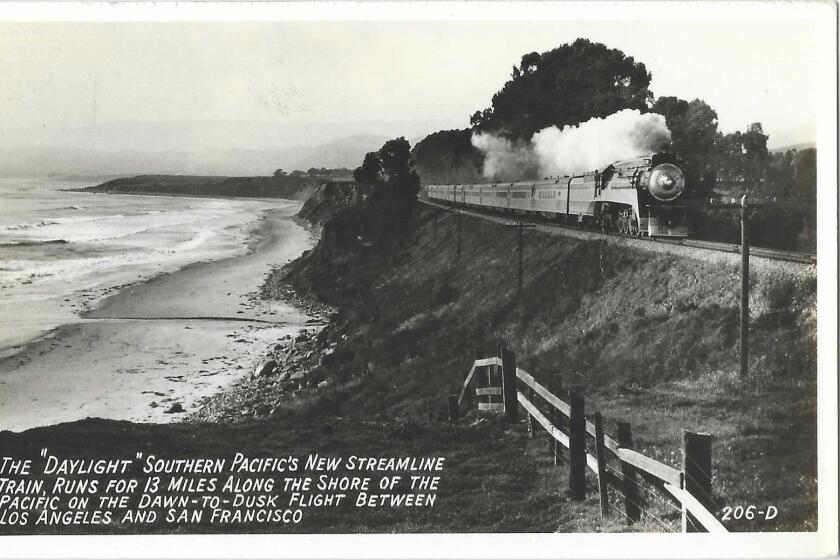

The beauty of train trips used to be a key selling point. But with the Pacific Surfliner suffering the effects of climate change, safety and reliability may trump the pretty view.

Beyond the disappearing local newspapers and women’s vaster choices, I couldn’t hazard a guess about the fate of pageants. So I besought Hillary Levey Friedman’s insights. She’s a sociologist who comes by her knowledge via degrees earned from Harvard, Princeton and Cambridge, and from personal touchstones: Her mother was Miss America 1970, and Friedman did a three-year turn as president of Rhode Island’s National Organization for Women chapter. Her recent book is “Here She Is: The Complicated Reign of the Beauty Pageant in America.”

I did have this bit right, she told me: “pageants all-around are just not as popular.” They’ve been dwindling away even as “the pace of pop culture goes a lot quicker these days.”

Pageants sponsored by local businesses and industries, like some of those businesses themselves, have disappeared from American culture and commerce. And around the country, many pageants “were run by organizations like the Jaycees,” and as some service groups have seen chapters and membership disappear, she said, you see a parallel decline in the pageants they sponsored.

Friedman was traveling in the West over the summer, and went to a rodeo in Jackson, Wyo. “It’s a big tradition in rodeo to have pageants and pageant queens, and it’s tied in to horses.” But she read in the local newspaper that there was only one candidate for the rodeo queen title. That woman won it anyway, and had earned it; a big write-up in the paper gave full marks for her achievements and goals.

“I’d say the rise of reality TV has impacted many things, in particular things like the Miss America pageant,” Friedman says. The pageant is no longer the only game in town, and even Miss America “is no longer the only way. Carrie Underwood tried to be Miss Oklahoma and didn’t win, but she won ‘American Idol.’ ”

And for a half-century, the groundbreaking Title IX, Friedman pointed out, has delivered more plentiful options and opportunities for women in sports — and I would venture to say has given women healthier and more varied notions of what women’s bodies should look like.

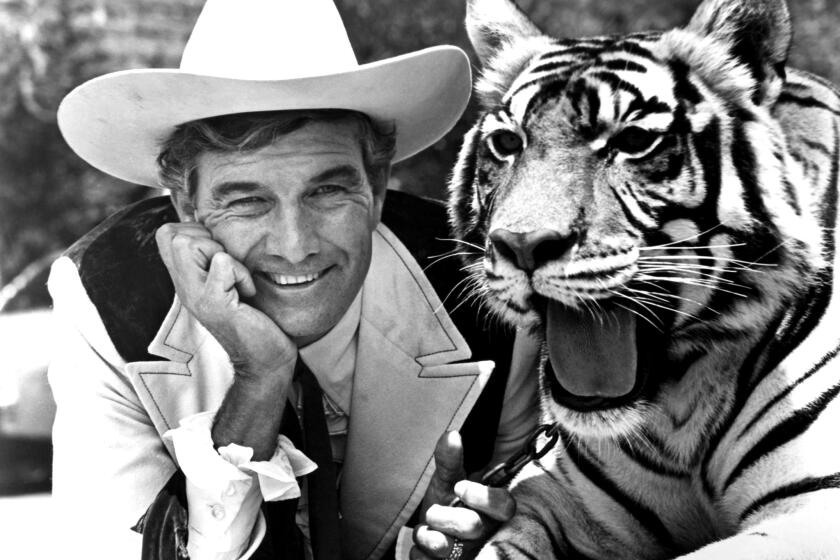

Cal Worthington (and his ‘dog’ Spot), ‘Madman’ Muntz and other colorful local pitchmen used to claim space in the public consciousness. Our culture may no longer be built for that brand of commercial antics.

Don’t expect the pageant world to take its tiara and slink quietly home to its yoga pants. Friedman says the South in particular is still the land of pageants. “There’s always going to be an audience; I think pageantry just takes different shapes. ‘The Bachelor’ in some sense is a reincarnation of what Miss America used to be. ‘RuPaul’s Drag Race’ show has a lot of elements of the pageant in it.”

(Trans women can compete in some pageants, including Miss America, but the San Francisco Standard reported that Miss A contestants’ contract, which used to require simply that they be “female,” now requires that they identify as either “a born female” or a female who has “fully completed [sexual reassignment surgery]/gender-affirming surgery from male to female, with accompanying medical certification.”)

The culture trap about pageants is that they were often treated like a societal measuring stick — and came up dissonantly, mortifyingly short. In 1948, the same year that President Truman ordered the U.S. Army to be desegregated, the Miss A contract specified that contestants be “in good health and of the white race.” The first Black Miss America, Vanessa Williams, was crowned in 1983 and was asked to resign nearly a year later when a skin magazine published nude photos of her without her consent. The pageant apologized to her — almost 30 years later.

Pageants for women of color thrived in parallel to whites-only events, and still do, even though women of color have begun to fill the ranks of famous pageants. Los Angeles still has a Miss L.A. Chinatown, and a Miss Nisei Week.

New pageants like HeartShine offer “body-positive” titles for older women, girls, and judge on an “ ‘inner-beauty’ standard … authenticity, poise, and leadership skills.”

For the kind of hopeful young women who once packed their sashes in their valises and got on the bus to come to Hollywood, only to find a hundred other small-town beauty queens already here, a pageant crown no longer has to be their only onramp to mobility and even cinema celebrity.

But it did happen for some of them: Michelle Pfeiffer, Halle Berry, Eva Longoria, Michelle Yeoh, Gal Gadot; and the most celebrated of them all, the two-time winner, in 1948 and 1953, of the Los Angeles Press Club’s “Miss 8 Ball” honors, an L.A. homegirl named Marilyn Monroe.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.