‘Ain’t a damn thing changed.’ Black L.A. skeptical a year after racist audio leak that roiled City Hall

One year since the leaked recording of a backroom conversation among three Los Angeles City Council members and a prominent union president rocked local politics and opened up old racial wounds, the healing process for many Angelenos is still ongoing.

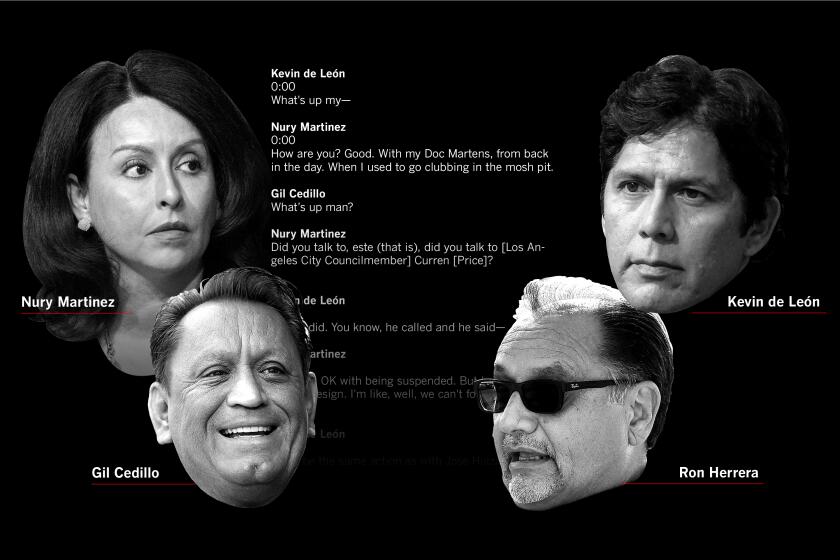

The four Latino political leaders — Councilmembers Kevin de León, Nury Martinez and Gil Cedillo, and L.A. County Federation of Labor chief Ron Herrera — took part in a conversation that included profane and derogatory comments about Black people, Oaxacans and others, and how to bend the city’s redistricting process to their own benefit.

Martinez and Herrera resigned amid the fallout. Cedillo is also no longer on the City Council, having lost his reelection bid months before the audio was released; De León is running for another term in March.

The Times spoke with Black Los Angeles residents this week to ask whether they thought anything had changed in the year since the racist audio leak was published.

A bombshell recording has thrown L.A. politics into chaos. What was really being discussed? L.A. Times reporters and columnists pick it apart, line by line.

Here is what they had to say:

Ariana Brewer

Shop manager at Coffee del Mundo

Brewer, 33, shop manager at Coffee del Mundo in the Vermont Knolls neighborhood, is an optimist at heart.

She isn’t surprised that elected officials would express their racism behind closed doors, she said, because the imbalance of care is clear in Black communities across the city. She’s hopeful that the people in those communities are capable of doing the work to call out those officials.

“You don’t climb to the top of office without being so dirty and brash and putting down a certain group of people,” Brewer said. “We have to be better. I can’t afford to be negative.”

Since the audio recorded at the labor federation headquarters was leaked, Brewer said, leaders in South L.A. neighborhoods have taken the initiative to bridge the gap between Black and Latino communities, because they don’t feel elected officials care about them.

“Our business is a bridge. We serve multiple groups — Latino, Black and all other people — because not just one culture lives in the city,” she said of Coffee del Mundo, which hosts community workshops for small-business owners and is open three days a week.

As a steady stream of patrons entered on a warm weekday morning, Brewer paused to prepare an iced coffee for one regular before they walked in. She resumed sharing her thoughts about the last year and how Black and Latino communities have reacted.

“I think that we share so much similarities in our struggles, with our mirrored backstories fighting against oppression. But our cultures are rich and vibrant,” she said over the sound of a coffee grinder.

“That’s all we really can do for each other,” she said. “Once I realized that I could take accountability for my own joy, it felt like a cheat code.”

Dermot Givens

Political consultant

“Nothing has changed,” Givens said. “Ain’t a damn thing changed.”

When Givens first learned of the recordings, he was upset but not surprised. Los Angeles politics has long been racial and polarized, he said.

“It’s nothing new; it’s just that it’s been exposed,” he said.

Asked whether the recordings had changed anything in Los Angeles politics, the attorney and political consultant offered a terse answer: “Nothing.”

“The council people are still behaving the same way,” he said. “The issue, the racism, is still there.”

For Givens, that’s observable not just in the makeup of the City Council but also in that of their staffs.

“There are three African American council people,” he said. “No increase, no decrease. There’s soon to be a decrease — there will probably be a decrease — but we don’t know.”

At the core of the tapes, Givens said, was the continuing struggle for representation in Los Angeles politics, including a growing Latino population and Latino politicos looking to increase their power in the council chambers.

But representation and power in City Hall can take many forms, he said, including the people who “actually run the place.”

“If you look at the non-African American council people and their staff — chief of staff, professionals — have they multiculturalized their staff?” he asked, before quickly answering the question himself. “No.”

Bernard Parks Jr.

Son and former chief of staff of former Councilman Bernard Parks

“I try to be the biggest optimist I can be,” Parks said. “But the system has not changed, and the ideas they’re talking about to remedy these problems are not innovating. They’re just self-serving.”

Recent ideas for changes, such as expanding the number of City Council seats, would not address the core of the problem, he said.

“Why would you think the answer is you need more people that make bad decisions?” he said.

Parks pointed to a series of recent criminal cases implicating elected leaders.

Councilmember Curren Price was charged with 10 counts of embezzlement, perjury and conflict of interest this year, and Councilmember Mark Ridley-Thomas was found guilty of conspiracy, bribery and fraud.

Councilmembers Mitch Englander and Jose Huizar pleaded guilty to federal charges of corruption.

The recent indictments and the racist comments made in the tapes as the politicians discussed redistricting are connected pieces of a system designed to serve leaders’ interests, Parks said.

“When you look at what the group was talking about, which was illegal redistricting ... and putting resources from one community to another to benefit themselves personally,” he said, “the important question is: Has anything changed inside of that building? And the concerning thing is the continuing string of indictments.”

Carol Parchue

South L.A. resident

At a nail salon near Western Avenue and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, Parchue, 53, spoke of the recordings in which Martinez insulted the Black son of former Councilmember Mike Bonin and compared him to an accessory.

“It was so insulting to hear that,” Parchue said. “This was a person saying something so awful, and for no one else to speak up and stop her was also so bad.”

Parchue couldn’t believe it had been a year since the racist comments were released, but she was surprised that De León is still in office.

“His reaction to the comment about the Black child said so much,” Parchue said. “It was not good for Black folks. I leave it to God, but it’s so bad.”

Over the last year, Parchue said little had changed in her South L.A. neighborhood. Parchue, who is originally from Belize, has not noticed a difference in how her Latino neighbors speak to her.

“We communicate just fine. I don’t think anyone I know felt hurt from those racist comments. It wasn’t nice, but it doesn’t change how I feel about my neighbors,” she said.

Janet Denise Kelly

Executive director of youth development organization Sanctuary of Hope

Kelly, 50, felt a deep betrayal when she heard the familiar voices on the tape. Martinez and De León, after all, had championed progressive policies around housing and help for homeless people.

“I still think that every day when our City Council members show up to do the work of the people, that elephant remains in the room,” she said while sitting down for lunch at South L.A. Cafe in Leimert Park.

Kelly acknowledged there is a struggle around who moves into positions of power and who is represented as the city’s demographics change.

During the secretly recorded meeting, Martinez, Cedillo and De León discussed ways of ensuring that key assets, such as sports arenas and recreation areas, remain in districts that are heavily Latino.

To Kelly, that felt like an egregious abuse of power that tried to pit groups of people against one another.

“It shouldn’t be a process where it feels that someone is pulling the strings or toying with that process,” Kelly said. “Especially for people in prominent positions of power.”

She still feels deeply hurt and does not think any real healing has begun.

“We have to rebuild that circle of trust,” she said. “It hasn’t started yet.”

Anson Roberts

Retired handyman

Roberts, 67, caught his breath under a bus awning on MLK Boulevard. Last year, his grandchildren played a portion of the racist audio while he was at a family function.

“I thought it was a movie,” he said. “I didn’t know these people were from City Hall. What do they have to gain from saying that?”

Roberts, who retired during the pandemic, feels like so many people are suffering in the city, but he can’t say whether that’s because of what was said in the leaked audio.

“Politicians are always going to be racist,” he said. “I don’t know if things have gotten better over the last year. You can’t measure it. There’s a feeling that we work so hard, and then it turns out someone has their foot on your foot, so you can’t move.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.