More than 75,000 Kaiser workers go on strike amid clash over staffing, wages

More than 75,000 Kaiser Permanente workers in California and elsewhere walked off the job Wednesday in what labor leaders described as the biggest strike by healthcare workers in U.S. history.

The Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions said workers were protesting “bad faith bargaining” by Kaiser executives as unions negotiate over wages and other issues that labor leaders contend have resulted in chronic understaffing.

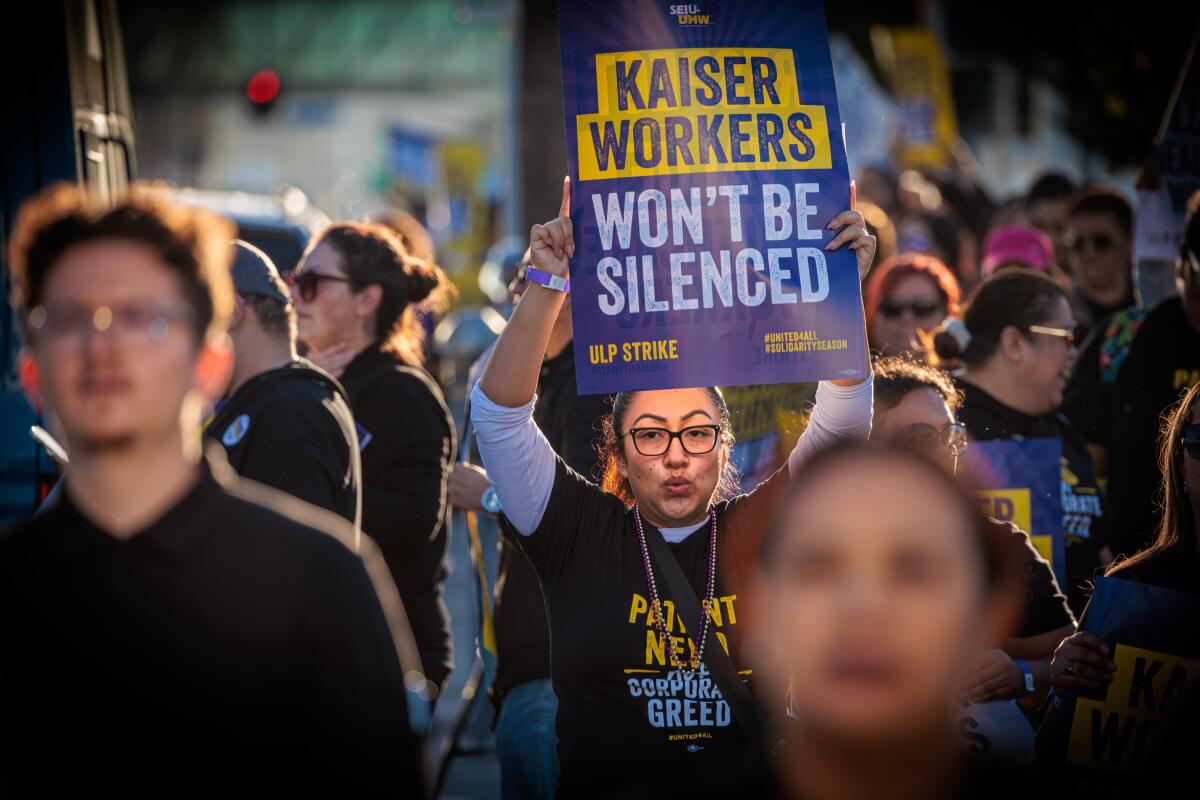

In Los Angeles, crowds of workers cheered, chanted and hoisted signs urging Kaiser to respect healthcare workers and “put patients first.” Drivers passing by Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center honked to show their support.

“Healthcare workers want to be at the facilities with their patients,” said Renée Saldaña, spokesperson for SEIU United Healthcare Workers West, which represents nearly 60,000 workers in the coalition including nursing assistants, housekeepers and medical assistants. “They’re doing this for their patients because of the delays in care, because of the short-staffing crisis.”

Armando Velasco, an X-ray technologist who has worked more than three decades at the medical center on Sunset Boulevard, said staff shortages forced him into “doing the job of five techs.” The workload left him exhausted and worried about patients’ getting enough attention.

“It’s just unfortunate for the patients that their service is lacking because Kaiser refuses to sit down in good faith to bargain and address that,” Velasco said. “It’s about patient care.”

Kaiser leaders said that they had bargained in good faith and that solid wages, benefits and other employee support helped Kaiser weather the national strain on healthcare staffing better than other providers. They said employee turnover at Kaiser was far below the industry average.

In addition, the health system announced Wednesday that it had reached a goal of hiring 10,000 new employees represented by the coalition, hitting that target “three months early.”

“Across the country there’s been a staffing crisis, and we have not been immune to that,” said Michelle Gaskill-Hames, president of Kaiser Permanente Health Plan and Hospitals of Southern California and Hawaii. “We’ve had the challenges, but we have been leaning in heavily to try to address them.”

At the bargaining table, “the discussions are down to wages,” she said. Oakland-based Kaiser prides itself on being a good employer, Gaskill-Hames said, but “we’re also committed to being affordable” for Kaiser members seeking care.

Tens of thousands of Kaiser Permanente employees in California and other states plan to go on a three-day strike starting Wednesday. Here’s what patients and others need to know.

The Kaiser workers on strike include licensed vocational nurses, X-ray technicians, surgical technicians, phlebotomists, certified nursing assistants, pharmacy technicians and respiratory therapists, as well as support staff such as housekeepers and food service workers.

Workers involved in the massive strike make up more than a third of Kaiser’s nationwide workforce and include employees in California, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Virginia and the District of Columbia. In most states, the strike is slated to last for three days; in Virginia and the District of Columbia, it will be a single day.

Union leaders have warned, however, that if Kaiser persists with “unfair labor practices,” a longer and bigger strike could follow in November. The union coalition alleged that Kaiser refused to provide information it requested during negotiations, among other complaints.

Licensed vocational nurse Angelica Mateo, who works at a Kaiser facility in Pasadena, said that workers are strained by the “the fact that we have so many employees that have to commute one to two hours ... because they can’t afford to live where they work.”

Once they do get to work, “we’re too busy to provide the care that we want to to our patients, that they deserve,” she said. “The pandemic definitely worsened this staffing crisis, and we’ve never really recovered from it. ... We see it every day because we’re the ones that are face-to-face with the patients.”

Michelle Rodriguez, another licensed vocational nurse working in Pasadena, said short staffing has led to upsetting delays in patients getting needed appointments.

“How do you look in a patient’s eyes and tell him, ‘We can’t get you an appointment’?” Rodriguez said. “They’re practically crying at your desk. ‘Well, I had this test, my test was abnormal. What do you mean I can’t get in?’”

Kaiser said in a statement Wednesday that management and union representatives had worked through Tuesday night to try to reach an agreement ahead of the strike and had made “a lot of progress.”

“Wages and benefits make up about half the cost of healthcare in America, so we all need to work together on that critical goal,” the health system said in its statement. Inflation has driven up expenses for healthcare providers, it added, and “in the wake of the pandemic, demand for care has increased dramatically as people come in for care that has been delayed. Kaiser is not immune to these inflationary pressures.”

Gaskill-Hames said that despite the tens of thousands of missing workers Wednesday, the goal for Kaiser was “minimal disruption” for its members, which include some 4.9 million people in Southern California alone. Some patient appointments might have to be rescheduled during the strike, she said, but Kaiser was “committed to staying open as much as we can.”

Kaiser indicated on its website that some of its laboratories in Southern California would be temporarily closed, including sites in Glendale, Baldwin Park, Lancaster, El Cajon and elsewhere.

To minimize disruption, Kaiser officials said they were marshaling existing employees to help cover needs during the strike, as well as bringing in an unspecified number of replacement workers.

Kaiser also said it could turn to retail pharmacies such as Rite Aid and Walgreens to help serve its members if any of its outpatient pharmacies needed to close, adding that no such closures would occur in Southern California. Gaskill-Hames also said there had been outreach ahead of the strike to alert Kaiser members that they could use mail-order services for needed medications.

In the San Fernando Valley, several patients leaving the Panorama City Medical Center said things had seemed normal inside the hospital, even as a crowd of workers picketed nearby on Woodman Avenue.

And in Hollywood, Rachel Schoenbrun said that the only thing that seemed different about her visit to Los Angeles Medical Center was that “they didn’t take a copay.” The Toluca Lake resident said she was told that because of the strike, she would get billed for that cost instead.

The recent run of wins in the Legislature for organized labor was remarkable. Now Gov. Newsom must decide if union-backed bills will become law.

Raises have been one of the sticking points in negotiations between Kaiser and the unions. Labor leaders said the wage hikes proposed by Kaiser executives wouldn’t keep up with surging costs faced by workers. They also balked at the idea of offering workers in some regions bigger raises than in others, calling it a “divide-and-conquer strategy.”

Kaiser said the differing raises are needed to ensure that its pay rates in each region are tailored to what local workers in different parts of the country can make for similar jobs.

Last month, Kaiser said it was offering “across-the-board wage increases” ranging from roughly 10% to more than 14% over four years, with bigger raises proposed in regions where its pay isn’t at least 10% above local levels for similar workers. More recently, it said it had proposed hikes ranging from more than 12% to 16% over four years.

The unions said the proposed amounts are inadequate and have been seeking four years of roughly 6% annual increases to base wages for workers in all regions.

The two sides have also clashed over a minimum wage for coalition workers. As of Monday, Kaiser said it was offering a minimum wage of $23 an hour in California and $21 an hour in other states starting in 2024, with increases in each year of the contract. The unions have been seeking a $25-per-hour minimum wage.

The labor organizations have pushed to mandate a $25-an-hour minimum through a California bill now in the hands of Gov. Gavin Newsom, but union leaders said it also needs to extend to workers in other states. Saldaña of SEIU-UHW cited “the cost of living in places like Portland, ... Seattle [and] Denver,” saying that “workers there as well have been struggling to keep up with inflation.”

Angela Balam said she earns $19 an hour as a housekeeper at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center. She said she had regularly worked 16-hour days because the hospital needed people to cover extra hours, and because she was trying to make ends meet for herself and her 3-year-old daughter. She said thin staffing has meant patients sometimes have to wait longer for rooms as housekeepers hustle to get them cleaned.

When she mentions that she works at Kaiser, “people say, ‘Oh wow, Kaiser’” because of its reputation for paying well, Balam said in Spanish. But “the pay we have isn’t sufficient for our family.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.