Why it took 27 years for an arrest in Tupac Shakur’s Las Vegas killing

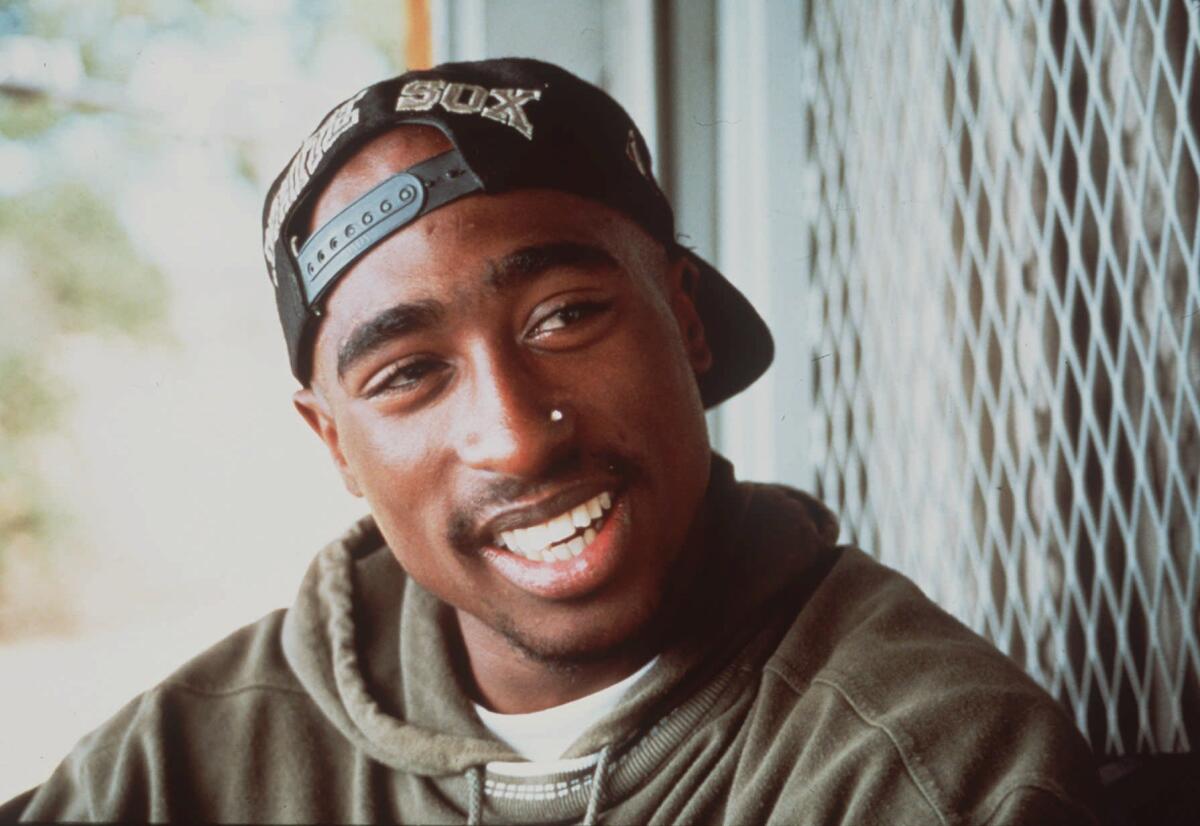

Nearly three decades ago, Tupac Shakur was riding in a BMW driven by Death Row Records boss Marion “Suge” Knight. They passed the MGM Grand Hotel and Caesars Palace on their way to a new Las Vegas nightclub.

A white Cadillac pulled alongside the BMW. A gunman opened fire, mortally wounding Shakur.

The killing shocked the music world. But the lack of an arrest in the high-profile case gave way to decades of speculation and theories in books, news articles and documentaries about what happened — and why police could not crack the case.

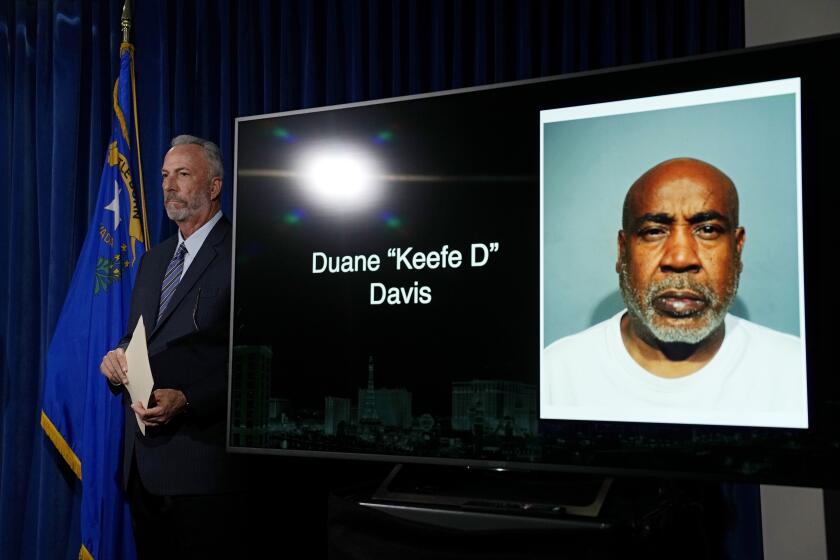

Then on Friday, Las Vegas authorities charged Duane “Keffe D” Davis, 60, with murder. Davis has long acknowledged he was in the car that pulled alongside Shakur.

Duane ‘Keffe D’ Davis, 60, is indicted on a charge of murder in connection with the 1996 shooting death of rapper Tupac Shakur in Las Vegas.

Authorities now claim that Davis masterminded the killing as an act of revenge over an escalating gang feud.

Here is what we know.

Why did it take so long for authorities to bring charges?

Many have wondered why the case was cold for so long, and police have been criticized for failing to make an arrest.

Ironically, authorities now say a break came thanks to Davis himself.

In his 2019 book, “Compton Street Legend,” Davis detailed those experiences and said he hid the Cadillac and the gun after the shooting and had the vehicle repaired and repainted before returning it to a rental car company.

Las Vegas Sheriff Kevin McMahill said at a news conference Friday that although detectives have had plenty of evidence in the case, Davis’ own admissions gave new life to the investigation in the last five years. “We knew at this time that this was likely the last time to take a run at this case to successfully solve this,” McMahill said.

In his 2019 memoir and in several interviews, Davis admitted to riding in the car from which the fatal shots were fired at the Los Angeles hip-hop legend. Davis was taken into custody Friday morning.

Police searched Davis’ home in Henderson, Nev., in July using a warrant that allowed them to seize materials they said were connected to the shooting.

Among the evidence seized were .40-caliber cartridges, computers, photos and other materials, records show.

“I know a lot of people have been waiting for this day,” Clark County, Nev., Dist. Atty. Steve Wolfson said at the news conference.

But it remains unclear why it took four years from the time Davis’ book was published to build a case.

Officials said a grand jury had been seated for months to help bring new charges in the case.

What do authorities allege happened?

The night of the shooting, members of the rival gangs attended a Mike Tyson boxing match at the MGM Grand. Afterward, Travon “Tray” Lane spotted Orlando Anderson in the elevator and recognized him as one of several rival gang members who had tried to steal a Death Row necklace from him during an earlier brawl.

Lane alerted Shakur, who then attacked Anderson.

After learning of the attack, Davis “formulated a plan to exact revenge upon Mr. Knight and Mr. Shakur, and in furtherance of that, he acquired a .40-caliber Glock firearm from a drug associate he had,” Chief Deputy Dist. Atty. Marc DiGiacomo told the court in announcing the murder charges.

Prosecutors allege that Davis and other Crips members drove in two vehicles to Club 662, where Shakur was supposed to attend a concert. When the rapper did not show up, Davis and the others went to a liquor store, where Davis got out of a van and into the Cadillac.

Nearly 30 years after the infamous shooting death of the hip-hop legend, Las Vegas police have served a search warrant at a home in the nearby suburb of Henderson, Nev.

“‘I don’t want to be in the van anymore because these individuals aren’t down with what I want to do: Go shoot Tupac Shakur and Marion ‘Suge’ Knight,’” the prosecutor recounted Davis as saying.

When Davis got into the Cadillac, he handed the Glock to two individuals in the back seat, DiGiacomo said, noting that Terrence Brown was driving and Anderson and Deandre Smith were also in the car.

As they drove west on Flamingo Road, they spotted the caravan with Knight and Shakur. “There was an order for them to do a U-turn,” DiGiacomo said. “They pulled up next to the vehicle as the rear passenger fired a number of rounds out of that vehicle, striking Knight and Shakur in the head several times.”

What role did gangs play?

Las Vegas authorities on Friday alleged the shooting had deep ties to Los Angeles gang rivalries.

In his 2019 book, Davis detailed how he was the “shot caller” of the South Side Compton Crips. “Or, as he put it, ‘We were in the Army. I was the five-star general,’ ” DiGiacomo said, noting that Davis was the “on-ground, on-site commander” who “ordered the death” of Shakur.

Like Davis, Anderson was a member of the South Side Compton Crips, authorities said. Shakur and Knight were affiliated with a rival Compton gang, the Mob Piru Bloods; Shakur’s bodyguards were also members of the Bloods.

“The Mob Piru were in competition ... with another gang by the name of South Side Compton Crips,” DiGiacomo said. “By mid-1996, there wasn’t much of a distinction between Mob Piru and Death Row Records,” Knight’s record label, he said.

Knight was sentenced to prison in 1997 for a probation violation stemming from the beat-down of Anderson. The four gang members who participated in the Las Vegas beating were Lane, Alton McDonald, Roger “Neckbone” Williams and Aaron “Heron” Palmer.

Lane was sent to prison for his role in a drive-by shooting; Williams was jailed on a weapons violation; Palmer was killed in a drive-by shooting in June 1997; and McDonald was gunned down April 3, 2002, while filling his SUV with gas.

Knight pleaded no contest to voluntary manslaughter in connection with the 2015 hit-and-run death of a man outside a Compton restaurant after a dispute related to the film “Straight Outta Compton.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.