Column: For nearly a century, this camp has hosted city children. Tropical Storm Hilary destroyed it

NEAR ANGELUS OAKS — Camp River Glen’s parking lot was swallowed by the Santa Ana River. The top of a tractor poked out of mud.

Gigantic water tanks were crumbled up like tissue paper. Leaves, branches, trunks and downed electrical wires were everywhere.

A month ago, preteens and teens from working-class families across Southern California were hiking, sailing and fishing here — many for the first time in their lives. They spent the night in cabins with no doors or windows, the better to let nighttime mountain breezes and the gurgles of the river lull them to sleep.

On the night of Aug. 20, a week after the campers had left and volunteers had just closed up for the season, the river tore through the 11-acre campsite, owned by the nonprofit UCLA UniCamp

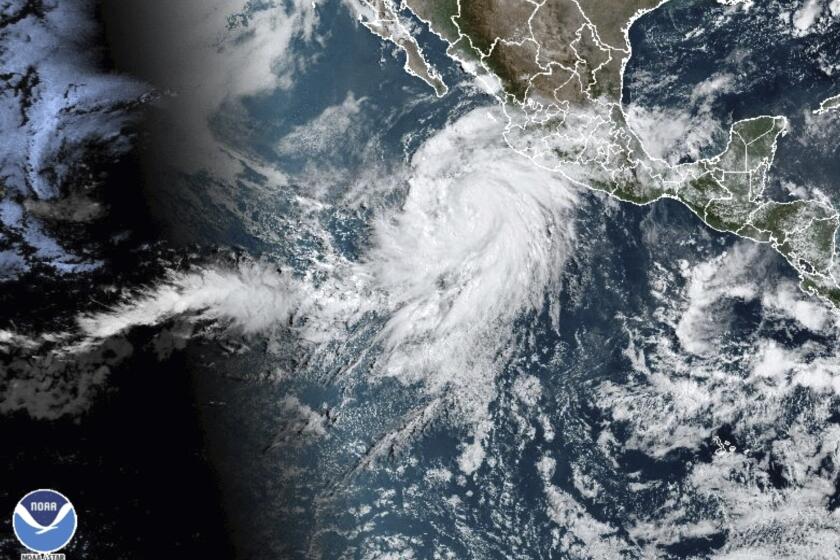

Tropical Storm Hilary engorged the waterway, usually just a dawdling stream during the summer, widening its banks from 15 to 100 feet.

Now, UniCamp Executive Director Jason Liou has to figure out whether the camp, which has hosted disadvantaged young people since the 1930s, will come back to this location next summer — or ever.

Storm damage is so bad in this part of the San Bernardino Mountains that Caltrans has closed Highway 38, which leads to Camp River Glen and goes on to Big Bear, for 9½ miles in both directions through at least December for emergency repairs.

Southern California Edison spokesperson Gabriela Ornelas told me that the company doesn’t have a timeline on when electricity might return to the area “because it’s been difficult for us to get in safely.”

Vehicles can’t enter Camp River Glen until the destroyed bridge that leads to it is repaired, which has to wait until the one heavy-duty road leading in is fixed. UniCamp owns all the buildings and infrastructure on its campgrounds, but the land is leased from the U.S. Forest Service, which must approve all improvements. Other agencies that Liou needs to get in contact with include the Department of Fish and Wildlife (in charge of anything having to do with the Santa Ana River) and San Bernardino County for repairs to county roads.

An unprecedented tropical storm watch has been issued for Southern California as Hilary barrels north toward the United States.

“There’s going to be a lot of coordination [between agencies], and not just with that camp,” said San Bernardino National Forest public affairs specialist Gus Bahena, who said the Forest Service is nowhere near done assessing Hilary’s aftermath.

Liou started volunteering at the camp in 2001 and has been executive director for five years. “The children who come here open up, and so do the volunteers, and it’s inspirational to see how we all grow together,” he said.

This year’s camp was the first since the pandemic that “we weren’t trying to rebuild, but rather excel,” Liou added.

That’s why he was initially hopeful that Hilary, the first tropical storm to pass through Southern California in 84 years, had spared Camp River Glen, even though his staff was forced to leave under evacuation orders. But the morning after the storm, the owner of a nearby cabin sent some photos.

“First, you can’t really see anything because you have to take in everything,” Liou said. “Then you notice some buildings aren’t there.”

He paused. “It’s absolutely heartbreaking.”

I asked Liou if I could see Camp River Glen for myself. On a recent morning, I met him at a Home Depot parking lot in Redlands.

Two UniCamp employees, Byron Lutz and Megan Le, would drive an insurance adjuster in one car. Liou and I would go with Rey Cano, a Malibu-based real estate appraiser and longtime UniCamp board member who wanted to witness the devastation for himself instead of relying on photos and texts.

“A lot of the kids haven’t even been out of their own neighborhood,” Cano said as we began our drive. His daughter was a camp volunteer this summer, and he came up for the final weekend. “Getting them out here is healing.”

Redlands’ orchards gave way to Mentone’s barren frontyards, which gave way to oaks and pine trees as we wound our way up Highway 38 to Camp River Glen. I saw waterfalls and wildflowers and picturesque cottages that looked like photos out of an issue of Ranger Rick.

I also saw hills scarred by fires. On other slopes, towering trees were a sickly orange — the telltale sign of a bark beetle infestation. Cement trucks rumbled past us; metal culverts were stacked on turnouts, awaiting installation. For some stretches, a pilot car shepherded caravans of cars past work sites.

Cano asked Liou how the camp had fared, as we crept toward it. The mess hall? Spared. The bathrooms? Some flooding, but salvageable. The water source? Severed. The new water pump? Destroyed. Maybe new benches could be built from felled trees?

“Uh, that’s kinda taken a back seat right now,” Liou deadpanned. Then he got serious.

“The concern we’ve always had is for fire. It’s only been in the last couple of years that the river has become a problem. Our insurance coverage is mostly for fire or wind, but not storms.”

The trip up to Camp River Glen usually takes about 45 minutes from the Redlands Home Depot. It took us two hours.

After we passed through a California Highway Patrol checkpoint, Cano stopped at what used to be Camp River Glen’s parking lot. It was now the Santa Ana River.

“Ah, geez — whoa!” he groaned as we got out of his all-terrain Volvo. “No way — ugh!”

He and Liou began to take photos. Authorities had red-tagged two nearby private cabins.

“I can’t even imagine how it was the day of Hilary,” Liou said.

At the end of UCLA’s summer mountain camp, the counselors usually return to their sprawling Westwood campus, while their charges go home to the boroughs and barrios of Los Angeles.

The only drivable route near Camp River Glen now is a one-lane dirt back road. Cano slowly maneuvered his SUV over puddles, holes and ruts for about three miles before we finally got to a small hill overlooking the bridge to the camp, now reduced to a concrete island. Huge trees lay upon it like Q-tips on a bathroom counter.

We gingerly crossed the knee-high river, far off its original course. It was about 20 feet wide, fast and cold. On the other side were Lutz and Le, who had passed us earlier.

“We’ve come to this camp so many times we know it like the back of our hand, so to see all this is very shocking,” said Lutz, UniCamp’s 30-year-old camp director, as we walked to the campground. “Three weeks ago, I saw campers playing volleyball. Now.…”

He trailed off.

“Just to see all the work that’s required beyond our team, we don’t even know where to start,” said Le, UniCamp director of external relations. The 26-year-old pointed at a red-tagged cabin that no longer had a foundation post.

“Hey, Blitzen,” Le told Lutz, calling him by his camp name (Le goes by Lilo, Liou goes by Mr. Woooo. Cano? Gobble, because he was born in Turkey). “This was the first cabin I ever stayed in here.”

Problems were everywhere we looked, mixed in among nature’s beauty. Bear tracks led into the pool pump room, swamped in a foot of mud.

“We need to have a chainsaw day,” Cano said, trying to lighten the mood.

Everyone will come here at least once a week for the foreseeable future and do what they can until contractors can come in, whenever that is. For now, Cano is rallying his fellow board members to raise funds while Liou tries to figure out where UniCamp will happen next summer.

“It’s the only site I’ve ever camped at,” he said. “But UniCamp has existed at other campsites as well. It would be a hard move, but we’d be able to do it.”

We were now looking at a garage whose walls had caved in but that remained standing. A UCLA flag hung behind a shattered window.

“I feel like every time I come here, it sags more,” Liou said.

“It won’t survive the snow,” Cano responded.

“Do the Santa Ana winds come up here?” Lutz asked. Le nodded.

“That’ll knock it down,” Cano said.

We stayed silent. Off in the distance, the Santa Ana River roared.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.