Lawmakers approve Newsom’s plan to transform California’s mental health system

SACRAMENTO — The California Legislature on Thursday passed Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan to transform the state’s mental health system with rare bipartisan support, sending him a proposal for the March 2024 ballot that would expand substance abuse services and generate nearly $6.4 billion to build facilities to provide 10,000 new treatment beds.

The governor and his aides have spent months quelling concerns from counties and advocates for children and families about how his overhaul could shift funds away from existing services.

Last-minute changes that allow the funding to be used for secure mental health facilities also roiled civil rights groups, underscoring the challenges Newsom confronts as he tries to address a homelessness crisis that has scarred the state and could define his political legacy.

The Democratic governor has received resistance from all sides, including from some of the most left-leaning interests in his party, in his quest to create a new model.

“There’s no blueprint for how to solve homelessness, and if there was this would have been done a long time ago,” said Anthony York, a spokesperson for Newsom. “There have been some who have been concerned about change, but the governor has been leading the effort to say we need change in order to serve the thousands of people living on our streets.”

Republicans and Democrats in the Legislature agreed that Newsom’s plan isn’t perfect. But they shared stories about mental health and substance abuse challenges in their districts as they came together to endorse his solution in an atypical show of unity.

One of the bills passed unanimously in the state Senate.

“I think this is a great bill, a great start,” said state Sen. Shannon Grove (R-Bakersfield) during the debate on that bill, SB 326. “I just pray that you guys just keep moving forward and addressing the issues that need to be taken care of, to eliminate or at least reduce the serious issues that happen with homelessness in our state.”

She said the opportunity to support “whole-person care” was more important than any reservations.

“This is the right thing to do. This is the right time to do it,” said Sen. Susan Talamantes Eggman (D-Stockton) during floor debates on the bills. “This is a monumental, necessary thing to do.”

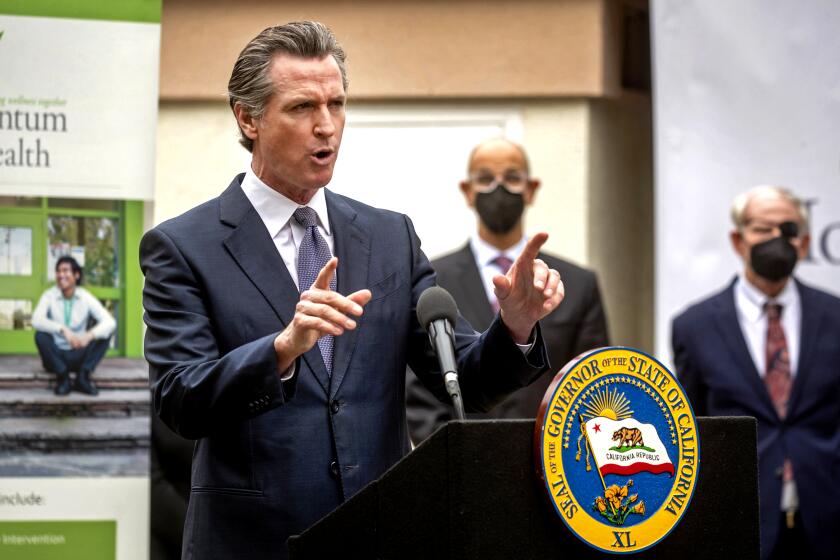

Gov. Gavin Newsom calls for sweeping mental health reforms to generate billions for behavioral health facilities throughout California.

The governor’s plan, unveiled in March, seeks to reform California’s 20-year-old Mental Health Services Act.

Approved by voters in 2004, the act established a 1% tax on personal income above $1 million per year to expand California’s behavioral health system to improve care and support for people with serious mental health issues. The money went directly to counties to spend on mental health programs.

Under Senate Bill 326, Newsom is asking voters to reconfigure the mental health law and set aside 30% of the tax, or about $1 billion a year, for supportive housing for those with serious mental health illnesses or substance use disorders.

Assembly Bill 531 creates a bond to generate at least $6.4 billion in one-time funding, which was increased this week from $4.68 billion, largely to build 10,000 new behavioral-health beds under a streamlined environmental permitting process. The bills will appear jointly as Proposition 1 on the state primary election ballot next spring.

Lawmakers also passed a bill that would make a major change to the mental health care system by expanding criteria for the detention, treatment and conservatorship of people with severe mental illness.

The governor contends that the changes in his plan are necessary to modernize the Mental Health Services Act to better meet the needs of today and to serve Californians with substance use disorders, which the state estimates at 1 in 10 adults, as well as those with serious mental health issues, a population of about 1 in 20. The legislation cites research by UC San Francisco that found 82% of homeless Californians reported having experienced a serious mental health condition and 65% reported regularly using illicit drugs at some point.

The proposal builds on Newsom’s ongoing effort to increase access to behavioral health services and build more supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness, which remains an entrenched problem for California and the Democratic governor despite billions spent by the state to address the issue.

Conservative media outlets and his GOP rivals repeatedly use images of encampments lining California sidewalks, which they cast as an example of the deterioration of public safety and civic order under his watch in the Golden State. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican presidential candidate, in June released a campaign video from San Francisco, where Newsom once served as mayor, bashing the “leftist policies” he says have led to rampant drug use and people defecating on the streets.

Seven counties will open their CARE Courts on Oct. 1. The state has estimated that 7,000 to 12,000 people will qualify for a treatment plan.

Newsom has acknowledged the pressure he feels to deliver results on homelessness in his second term to counter the narrative from the right.

Last year Newsom championed the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) Court to require counties to create courts with the authority to order treatment plans for people suffering from schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders. Counties had expressed concerns about lacking the funding to increase housing and beds to treat CARE Court participants. Civil liberties groups and disability advocates lobbied against the plan, which they argued would criminalize homelessness.

Concerns over his mental health plan this year focused on Newsom’s call to redirect money from existing services and programs funded by the act to housing. Advocates were worried that the new focus on housing, coupled with an end to mandatory mental health funding allocations for children and families, could leave one of the state’s most vulnerable populations short-changed in the squeeze for public dollars.

“Counties are under intense pressure to address what we see in encampments, and those are adults,” said Adrienne Shilton, director of public policy and strategy for the California Alliance of Child and Family Services. “Homeless youth that our organizations are working with, youth that are at risk, or families with children, they are not in encampments. They are a less visible homelessness population.”

Shilton said the governor’s office ultimately agreed to set aside about half of a county’s early intervention funds specifically for adults and youths under age 25, which was amended in the proposal. But there’s no such guaranteed allocation for housing support, she said.

Gov. Gavin Newsom wants to “modernize” how billions of dollars for mental health are spent, but Los Angeles County officials and others have raised concerns about his proposal.

Shilton pointed out that many children and families experiencing homelessness are not suffering from drug addiction or mental health issues, but instead find themselves unhoused because of issues of affordability in a state with an increasingly high cost of living. Without an across-the-board mandate for money for those populations now, the problem the governor is trying to address might only get worse.

“We will be creating the next generation of homelessness,” Shilton said. “That’s what we don’t want.”

Newsom’s office acknowledged the opposition from some advocates, but said there’s also undeniable frustration with the status quo from millions of Californians.

“I would assume everybody on this floor hears from your constituents about this very issue and the homelessness issue that’s across the state,” said state Sen. Janet Nguyen, a Huntington Beach Republican. “So I thank you, I thank all those who’ve been involved in moving this forward.”

AB 531 passed the Senate on a 35-2 vote and the Assembly 63 to 7 on Thursday. SB 326 passed 68 to 7 in the Assembly earlier this week and received unanimous support Thursday in the Senate.

Newsom said he was “deeply moved” by the stories Republicans and Democrats shared during the floor debates.

“These measures represent a key part of the solution to our homelessness crisis, and improving mental health for kids and families,” the governor said in a statement. “Now, it will be up to voters to ratify the most significant changes to California’s mental health system in more than 50 years.”

The bills now go to the governor’s desk. His signature will place the measures on the March 2024 statewide ballot.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.