PARADISE, Calif. — Whipping winds, a sky blackened by smoke. Fear, urgency and then panic as gridlock stymied escape and flames closed in, making car windows too hot to touch.

Barbara Bowen knows what the survivors of the Lahaina fire experienced because the same nightmare happened to her in Paradise, Calif., during the Camp fire in 2018.

“I thought I was going to have to break my animals’ necks rather than see them burn,” she said recently, remembering her harrowing journey down a traffic-jammed street with fire on all sides. In her car, along with her cats and dogs, were two men she found running down the road: Trevor Colston and the developmentally disabled man he helped care for, Dan Stoffer.

Five years after the Camp fire devastated Paradise in the deadliest wildfire in California history, Bowen, Colston and Stoffer have moved forward with their lives and the town is one of the fastest growing in the state, with construction on nearly every block. But the journey to recovery for the people of Paradise and the place itself has been hard and uneven. For those who left and those who stayed, the emotional trauma continues even as the physical restoration progresses.

“These kinds of fires, they erase your fingerprints on this world,” Bowen said. “The fire keeps taking and the aftermath goes on for years.”

The same difficult and inequitable future, many said, is likely for Lahaina, where the death toll continues to rise into the hundreds and talk of rebuilding has already begun. If Paradise offers lessons for Maui, they are a blend of hope and harsh reality: A new town will be different from the old one, just as the new lives of survivors will be different from what was.

Last week, the signs of recovery were everywhere in Paradise. Starbucks bustled, shoppers filled the Save Mart and school buses navigated their charges to and from the first days of classes. The town is home to about 9,200 people, said Mayor Greg Bolin, down from about 27,000 before the fire. New homes stretched for miles. About 500 were built last year alone, up from two or three a year before the fire, Bolin said.

But the thick canopy of Ponderosa pines and oaks that once made this place a shady mountain getaway — popular with urban defectors and retirees — are conspicuous in their absence. The sun beats down, unbroken by shade. As many as a million trees were burned or chopped down because they were dead or damaged. In their place are thousands of charred stumps sticking up like grave markers in empty lots and landscaped yards alike.

Along with the cooling, the privacy of the forest has disappeared. Paradise is now all about views: sweeping over canyons, up mountain peaks and down to the valley below — and into neighbors’ backyards, to the chagrin of some.

“It’s absolutely spectacular,” said Bolin, who in addition to being mayor also owns a construction firm that has built both spec houses and rebuilds for residents.

Emma Miller, 33, who works as the operations associate at the Paradise Ridge Chamber of Commerce, said she is thrilled with the changes in Paradise.

“The rebuild is amazing,” she said. “It’s cool to see houses being built, and people coming home, and new people moving in and taking pride in our community.”

Miller, who grew up in Paradise, was living in Texas at the time of the fire — she and her husband had moved there six months prior for his job. Their old home, which they had sold to friends, burned to the ground, as did her parents’ home.

But the disaster in Paradise enabled her family to come home, she said. Her husband got a job working for a contractor. Her 5-year-old daughter will go the same elementary school he attended.

“I feel like the millennial generation is moving here,” she said. “You get more land for your money here. Having that white picket fence dream is possible in California. Definitely different from L.A. and S.F. and even Sacramento.”

That Paradise exists today is due largely to state and federal aid. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has spent millions of dollars and years cleaning up, and in 2019, the state worked to make Paradise and surrounding communities eligible for more than $500 million in federal funding to rebuild single-family homes in disaster areas.

In 2021, on the third anniversary of the fire, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office announced that it had removed tens of thousands of dead and dying trees and cleaned thousands of properties. In 2022, his office announced an additional $200 million in state block grant programs for recovery in Paradise.

On top of all that, Bolin said the city has netted, after expenses, about $220 million from a settlement with Pacific Gas & Electric, whose power lines ignited the fire, killing 85 people.

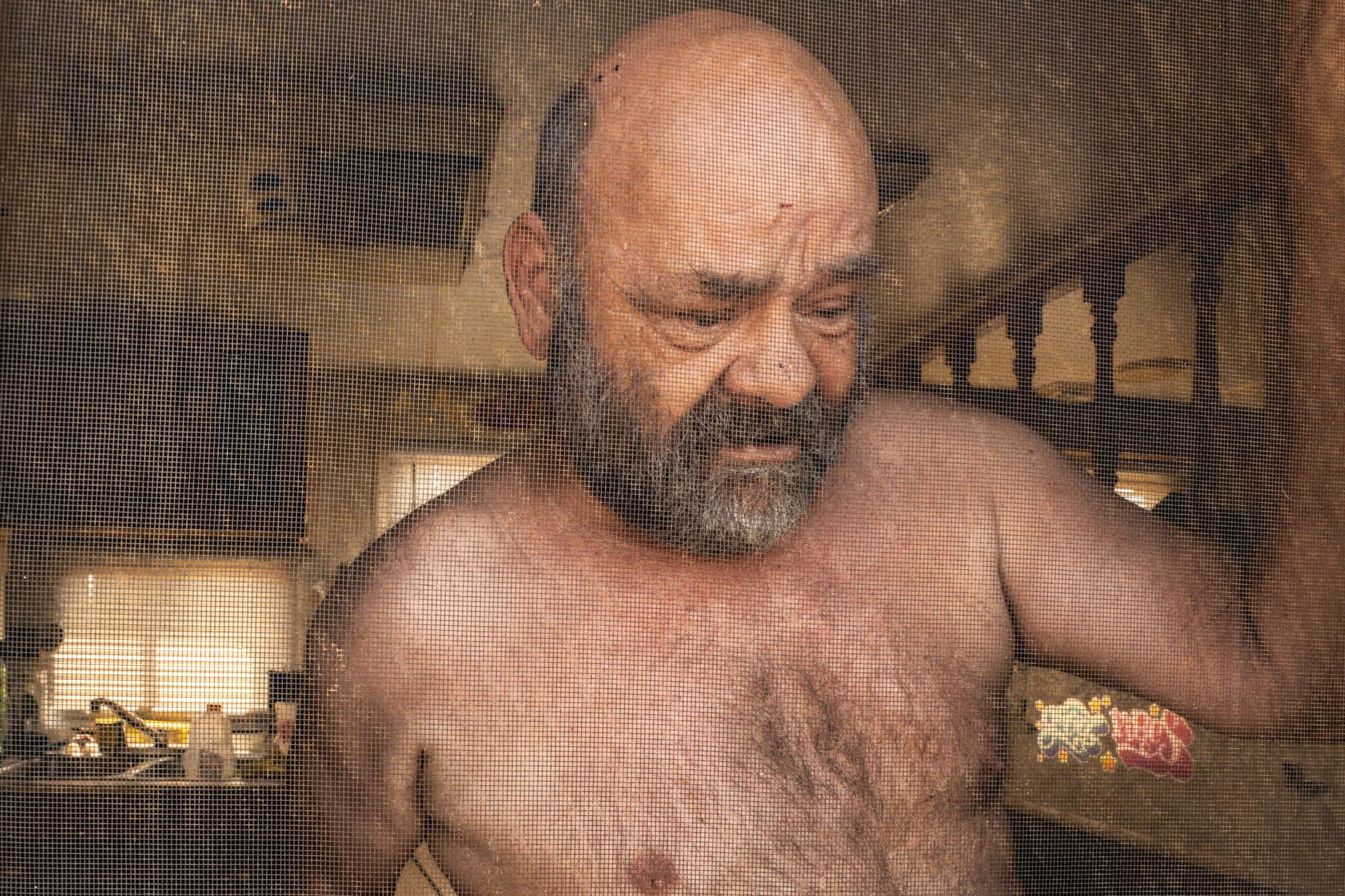

But for town councilman and former Mayor Steve “Woody” Culleton, it’s the regrowth of the “spirit of the community,” that makes him most proud of Paradise, and why he never considered leaving after the fire. He came to this town decades ago strung out on drugs and alcohol, he said. He had a history on the wrong side of the law and had burned nearly every personal relationship in his life.

In Paradise, he found acceptance and redemption, he said. Where once he was riding in the back of the town’s police cars in handcuffs, he wound up in the front seat with the chief of police, he joked.

“This is where I was reinvented. Everything has come together for me here,” he said. “People care about each other.”

*

But not all Paradise residents feel the inclusive warmth of community.

Like many who fled during the Camp fire, Joshua Stokes, 40, has watched the images of Maui with a mixture of deep sympathy and reignited trauma.

“When I saw Maui, it just took me back,” he said, suddenly breaking into tears.

But when Stokes saw that the town of Paradise had placed a note on its Facebook page for the people of Lahaina, he was outraged.

“You did that for likes,” he said. “If you really cared, we would be taken care of, and we are in your town.”

Stokes said he and many other residents are living in trailers or campers on their own land while they wait for settlement money from PG&E to build. But town officials are harassing them, threatening them and, in some cases, making it impossible for them to stay, he said.

“They are forcing people to be homeless,” he said. “I don’t want to leave this town, but they are forcing people like me out.”

The issue, he and others said, is how long people should be allowed to camp on their own land in vehicles without building. Many residents, including dozens who have joined a Facebook page titled Fighting the Town of Paradise While Rebuilding, say the town leaders are insensitive to the fact that people cannot rebuild until they wait for the lawsuits over the fire to pay settlements.

“The mayor said, we don’t want this looking like a trailer park,” Stokes said. “But you know, until people get their money from PGE and can rebuild, that’s how it’s going to look.”

Walt Munjar lives in a trailer park off the main road through Paradise, not far from its City Hall. He had a stroke shortly before the fire, and a more serious one a few months ago, and now uses a walker.

Like Stokes, Munjar said he felt unwelcome in the town he grew up in.

Climbing unsteadily down the rickety metal steps of his battered Coachmen Catalina, Munjar said he paid $600 a month to park the metal recreational vehicle on this gravel lot with no shade.

“Before the fire you could park a fifth wheel anywhere. Now they’ve made laws,” Munjar said. “The city, they got yuppie intentions.”

Bolin said the town has done everything in its power to help lower-income residents, especially those still waiting for payouts from PG&E. Grant money is being used to build senior and low-income housing, and some apartments are already up.

Bolin said the accusations that town leaders are trying to drive out poor residents are “very hurtful because that’s not the case at all.”

He also believes the camping can’t be tolerated forever.

“This is not a town where we want to continue to have people live in trailers,” he said. “It’s just very tough. I’ve lost a lot of friends in this situation. You just have to keep doing what’s right for the majority of the town.”

*

For some Paradise survivors, the aftermath of the fire brought the realization that Paradise was part of their past. Economically and emotionally, some of its residents were simply unable to return — a difficult decision that brought both regret and, in some cases, relief.

Trevor Colston was one of the men Bowen picked up as she fled, saving his life. Colston said that as he sat in the back seat, he felt that even if he survived, the future would be bleak. At one point, he considered jumping out and running into the flames rather than face what would come with survival, he said. But he thought such a death would be selfish, so he stayed and prayed.

But the trauma that came next left him feeling like a “soulless zombie.” He did eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy to help him with nightmares about being in Bowen’s truck.

For months afterward, he lived in migrant housing with his developmentally disabled clients, the only place his company could find for them. His own house burned in the fire, and he and his family ended up moving off the mountain to a town in the flatlands.

It took years to come to terms with all he had lost, he said. But now, he doesn’t see himself ever returning to Paradise.

“A year ago, it finally just started to be like, ‘You know what? I’m OK here,’ ” he said.

Dan Stoffer, the other man Bowen picked up, also has not returned — in part because the care home he lived in no longer exists. Now, he lives in a home in Redding, a much larger city that has brought him more opportunity.

An avid amateur radio operator, he has been able to get a ham radio license — a testing process he couldn’t have done in Paradise. And he’s been able to purchase a Ford F-150 which his caretakers drive him around in.

“Basically I have a lot more freedom,” he said. “I am pretty much more happier where I am at.”

Despite all that has been rebuilt in Paradise, it remains plagued by drawbacks that make life too difficult for some, especially vulnerable people, such as Stoffer, for whom the isolation was a disadvantage.

Its hospital, run by Adventist Health, which reportedly received more than $100 million in insurance and PG&E payouts, will not reopen.

About half of the town’s 200 miles of roads are privately owned, many of them the only egress for homes tucked into the hills. Those private roads were damaged by the FEMA cleanup, said Culleton, the town council member, leaving them bumpy and difficult to navigate.

But “all the federal government will do in its infinite wisdom is fix the public roads,” he said.

The town also has no sewer system — the largest community west of the Mississippi without one, Culleton said.

But most concerning for some is safety. Although the smaller population and removal of so many trees has drastically reduced the risk of another fire or evacuation disaster, new trees are growing and the town is working toward restoring its population — and inadvertently perhaps its risk.

A siren warning system recently went online, but many residents have expressed concern that it isn’t loud enough. Jamie Johnston, who lives a few miles from the town center in a rebuilt home, said she can’t hear the network of blaring towers at all though her new double-paned windows, and even outside it “sounds like little tinkle bells.”

Then there’s the issue of getting out. Culleton said no alternative evacuation routes have been built, and construction on a new road that would connect two others has not begun.

So how would residents escape in an emergency?

“The same old way,” Culleton said.

Does that worry him?

“Well, yeah,” he said, as if the question were dumb.

But Culleton also adds that restoring the town’s population is crucial to it’s future. Bolin, the mayor, said that even before the fire, Paradise’s government was “barely scraping by.” The PG&E settlement will provide it funding for as long as 30 years, he said.

“Unless we get back to what our population was pre-fire, we are not going to be sustainable,” Culleton added.

*

One thing survivors can agree on is that the trauma is ongoing. The Paradise residents who climbed into cars and trucks on the November morning of the fire have been changed by upheaval and suffering.

Maureen Culleton, Woody Culleton’s wife, loves her rebuilt home. It’s a jaunty forest green cottage surrounded by cherry laurels, with a meditation room for the practicing Buddhist and a statue of St. Francis on the back porch that survived the flames.

There is also a photo of the fire coming over Sawmill Peak, the mountain visible from the window of her mediation room. In it, puffy black smoke roils over the top, a heart of orange fire at its center. For a long time after the fire, she said she lived in shock that left her disengaged. She had been surrounded by the blaze and believed so strongly that she was going to die that she called her son to say goodbye.

Therapy and time have helped, but the photo is a reminder to stay strong.

“I wasn’t going to let it take over my life,” Maureen said. “It is what it is. Old ideas don’t work anymore.”

For Bolin, the mayor, the trauma is unresolved. In the wake of the tragedy, he felt like the town was depending on him to move forward and be the image of that needed strength. So he didn’t even think about the home he had lost, or the ones his family members had lost, he said. He just buried himself in the work of recovery for others.

Recently, he finally finished building himself a new home, overlooking a canyon. He and his wife haven’t moved in yet, but he plans on taking a break and finally focusing on family when he does. He knows it may be time to deal with his own feelings of loss.

For Bowen, who is also back in a home in Paradise, every day remains raw. She returned to Paradise to be near her elderly mother, who died last year. She feels trapped in a place where her community has fractured, and wishes she had not returned.

Her advice for those in Lahaina isn’t what most people want to hear in the first days of shock and pain. But Bowen thinks it’s important, because she wishes someone had said it to her: Don’t be scared to get out, and start a new life someplace where the next decade won’t be about sifting though the physical and psychic ashes.

“Even if you get back in a home, your life is forever changed,” she said. “I mean, you will never be the same person.”

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.