Column: He got his ‘End of Life’ medication within 48 hours. Will the option be there for others?

Matt Fairchild loved movies, he loved serving in the Navy and the Army, and he adored his wife, Ginger.

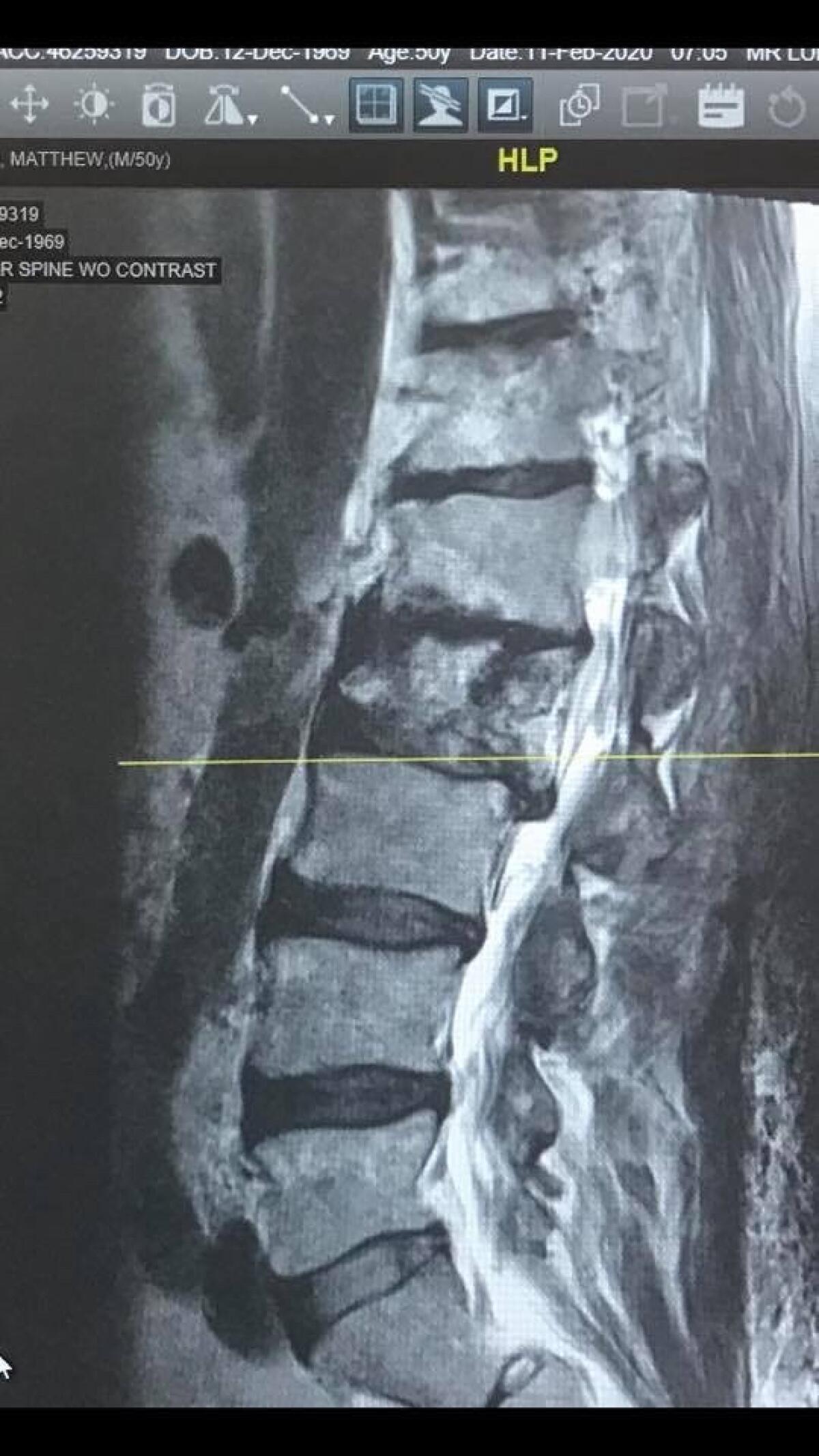

But for nearly 10 years, cancer assaulted him, beginning as a melanoma lesion near his ear before marching through his bones, brain and spine. Matt fought not just the cancer, but the effects of chemotherapy and other treatment. A rod had been inserted into his back after his spine was ravaged, and when the rod snapped, Matt told Ginger he wasn’t going back to the hospital.

Friends began dropping by the Fairchilds’ Burbank home in January 2022, with Matt, 52, greeting them from his hospice bed in the dining room.

“We had nurses coming in and out, and he couldn’t get up to go to the bathroom,” said Ginger, a registered veterinary nurse, who had been with Matt for more than 30 years. “He couldn’t push himself up…and he was so swollen from the steroids.”

California’s End of Life Option Act had just been tweaked to allow terminally ill patients to get life-ending medication in 48 hours rather than having to wait 15 days.

California is about to be hit by an aging population wave, and Steve Lopez is riding it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of advancing age — and how some folks are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

Matt, a supporter of Compassion & Choices, an advocacy group whose mission is to improve end-of-life care options, would be among the first Californians to act on the new provision. Not everyone who gets the life-ending prescription uses it. Of the 5,168 prescriptions written since the option took effect in 2016, about two-thirds have died from ingesting the medication.

Matt, who was Catholic, fought as long as he could, Ginger said. But when he knew he was ready, he wanted to get the medicine “as fast as possible.” Knowing it was on its way put him in a state of calm, Ginger said.

“It was really comforting, but it was also really sad and really hard,” she told me in the very room where this had played out. “He said that he didn’t want to leave me and that he loved me, and I told him that I’d be OK.”

They held hands. Matt drank the medication.

“And then he kind of laid back and went to sleep.”

Ginger is sharing this story now because California’s End of Life Option Act has been challenged in federal court. A lawsuit filed in April, with a hearing scheduled for next month, alleges that people with disabilities stand the risk of being coerced into choosing to end their lives because they don’t have access to quality care.

“Matt thought it was preposterous to think that anyone would be coerced,” said Ginger, who argues that ample safeguards are in place to make sure there’s no abuse.

The lawsuit, filed on behalf of several disability rights groups, makes the claim that California is “running a deadly system that steers people with terminal disabilities away from necessary mental health care, medical care, and disability supports, and towards death by suicide under the guise of ‘mercy’ and ‘dignity’ in dying.”

San Francisco civil rights attorney Michael Bien, who represents the disabilities groups, told me he doesn’t think the state should be in the business of helping people take their own lives. It should instead ensure that people with disabilities and people of all races and incomes get equal access to healthcare that allows them to extend their lives rather than cut them short.

I can’t argue with him about healthcare inequities. I did ask, however, if Bien thinks there are situations, such as that of Matt Fairchild, in which he supports a patient’s right of self-determination.

“I don’t think someone should be forced to live, and I think people have a right to die through natural means,” said Bien. “But I think it’s very dangerous to have doctors violating their Hippocratic oath and killing people…I want the doctor to play doctor, and not executioner.”

The lawsuit names two plaintiffs with severe disabilities.

One is a Black Navy veteran of limited means who is a formerly suicidal quadriplegic and “currently is unable to obtain the level of in-home care” he needs, according to the lawsuit. The Oakland resident “experiences anxiety and depression” and “fears that he will again become suicidal.”

The other is a white Berkeley woman with muscular dystrophy who uses a ventilator and “is fearful that her medical providers will steer her towards physician-assisted suicide in lieu of providing life-sustaining treatment during a time when she has impaired judgment due to anxiety and/or depression.”

State lawyers, in a motion to dismiss the lawsuit, argued that those two plaintiffs have not applied for aid in dying and might not be eligible. A person has to be deemed terminally ill, with less than six months or less to live, and must submit two requests for medication.

The requests must be witnessed by two adults — one of whom does not stand to benefit financially — who can attest that the patient is of sound mind. The physician who prescribes the medication must determine, among other things, whether the request for medication is being made voluntarily.

“There is no evidence...that the law steers anyone anywhere, or poses any harm to people with disabilities,” said a statement from Kathryn Tucker, an attorney representing several groups opposing the lawsuit, including the Golden West Chapter of the ALS Assn.

When I first wrote about right-to-die legislation, before California followed Oregon’s lead in 2016, I was a vocal advocate. My father, in his final years, surrendered much of what he had lived for, and it was that loss, rather than physical pain, that wore him down. He was, however, subjected to too many unpleasant and perhaps unnecessary medical procedures, and I remember him saying enough already when a doctor recommended a feeding tube.

My mother had a similar experience, and I still wonder — in a culture that has trouble accepting the natural course — whether we know the difference between extending our lives and prolonging our deaths.

After I spoke to Ginger Fairchild about Matt, I visited via Zoom with Bay Area poet Charles Entrekin, who is terminally ill, and his wife, Gail, also a poet. Charles is blind and has Parkinson’s; Gail cares for him. They both support the End of Life Option Act.

“I’d like not to be trapped into living my ending days drugged out and in hospice,” said Charles, who wants to hold onto the option of ending his own life, and I feel the same way.

The Entrekins sent me some of their poetry, and before I write more about their situation, I’d like to read the poems and pay them a visit.

“He’s walking a fine line,” Gail said of her husband. “Is there still some quality of life worth staying for? Or is it time?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.