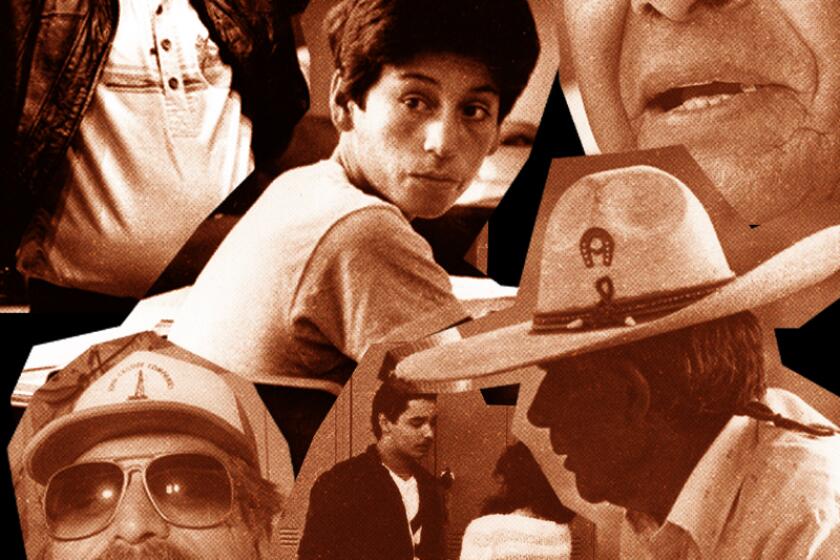

Watts’ Arturo Ybarra, the ‘epitome of what a community activist should be,’ dies

Arturo Ybarra, known as the founder of the Watts Century Latino Organization and for being tortured by the Mexican government for his college activism before the 1968 Olympics, died last month. He was 79.

Ybarra died July 27 of complications from pneumonia, according to his daughter Autumn Ybarra.

Ybarra started the Watts Century Latino Organization in 1990 and its goal was to empower and inform newly arriving Latino immigrants about their rights all while encouraging civil participation. The organization offered seminars on home ownership and community empowerment along with adult GED and English language classes to largely Spanish-only speaking residents.

Ybarra also served as the main organizer of the first Watts Cinco de Mayo festival parade. He spent months working with and incorporating ideas from various Black and Latino leaders.

The first parade in 1991 featured civil rights icon Cesar Chavez as the parade’s grand marshal. One of the most popular celebrities at the time, Todd Bridges of “Diff’rent Strokes” sitcom lore, also participated.

The event was meant to bring Latino and Black people together at a time when much talk regarding South Los Angeles and Watts, in particular, centered on demographic shifts and the clash between the long-standing but shrinking Black community and the growing size of its Latino neighbors.

More than four decades ago, groups of Black and Latino journalists embarked on an endeavor to tell stories about their communities that the Los Angeles Times was failing to showcase.

It was a narrative Ybarra, a Watts resident, rejected. The Afro-Latino, whose grandfather was born in Africa, believed “in the spirit of multicultural unity,” a motto he often repeated, Autumn Ybarra said.

“Arturo Ybarra was a bridge builder, a waymaker, a healer, and a foundational beam of our vibrant South Los Angeles community,” Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles) said in a statement.

Ybarra is survived by Albeza, his wife of 41 years, and his seven children, Nora Ostler, Hector Valencia, Danny Valencia, Sandra Cronk, Cristian Ybarra, Autumn Ybarra and Pahola Ybarra, and eight great grandchildren.

“I grew up not just in this family but in the organization my father built,” Autumn Ybarra, 34, said. “He wasn’t just a loving and accepting father, but a community cornerstone.”

One big tenet for the Watts Century Latino Organization and Arturo Ybarra was working with the Black community.

“He was courageous and just persistent in his efforts to bring the Latino and African American communities together,” said friend Arturo Vargas, chief executive of the Monterey Park-based National Assn. of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials. “He identified the common challenges they faced rather than focus on what divided them.”

The women set out on a brisk walk every Friday morning — past broken bottles, graffiti, an occasional stray dog and the smell of marijuana.

In September 1991, a fire ripped through Watts’ Jordan Downs housing complex, killing a family of five Mexican Americans, including three children. Latinos blamed a group of Black neighbors, but police speculated the blaze was less about racial motivations and more about backlash toward the family after it spoke out against a nearby gang.

Initially, some Latinos pushed for segregation of the projects between Latino and Black residents, but Ybarra called for calm and cooperation.

“We should stay together, work together and find a solution together,” Ybarra said at the time.

Ybarra’s arrival was a breath of fresh air for prominent Watts advocate Sweet Alice Harris, founder of the organization Parents of Watts, which offers services to foster families.

“Nobody had represented the Hispanic community in Watts before,” the 89-year-old Harris said. “He came and found me and we would always talk whenever there was a problem. We shared information and leaned on each other.”

Harris said she was “impressed” with the “mild-mannered and soft-spoken” Ybarra, who disarmed people with an unassuming charm.

“Whether it was problems with housing or education, he worked through his organization,” she said. “When we needed to join forces, we would.”

Ybarra’s call for unity resonated with mentee and fellow Watts resident Cynthia Gonzalez.

For decades, L.A. Black and Latino political leaders formed vital alliances. But these partnership now face unprecedented challenges.

Gonzalez, the director of Pardee RAND Graduate School’s community-partnered policy, said she “found a kindred spirit” in Ybarra, who believed in unity “between Black and brown people.”

Gonzalez attended Watts’ Grape Street Elementary School, Markham Middle School and King Drew Magnet High School.

“In my neighborhood, Black and brown [people] socialized,” she said. “We listened to each other’s music, ate soul food together, braided each other’s hair, had interracial marriages and tackled problems together.”

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Chicano/a studies in public health from UCLA, Gonzalez continued her schooling at USC with an intent to study and work in Watts.

“Every time I would ask someone a question about Latinos or structure or legacy leaders in Watts, I was constantly pushed toward Arturo,” she said.

The pair met in 2010 and Gonzalez said they spoke for six hours. She was inspired and studied Black liberation and anti-racist movements.

Gonzalez said Ybarra encouraged her to continue climbing higher until she finished her doctorate in cultural and social anthropology from San Francisco’s California Institute of Integral Studies in 2014.

“He was really proud and wouldn’t stop calling me ‘Dr. Gonzalez’ after I graduated,” Gonzalez said. “I was at an event picking up trash and he asked me, ‘Dr. Gonzalez, what are you doing?’ He just wanted to honor the work.”

The unity of two long-neglected communities during trying times is a reminder of what we desperately need in Los Angeles.

Gonzalez later became a founding member of the Watts Community Studio, which surveys residents and business owners about pressing issues.

Friends and family say Ybarra’s drive for social justice started at a young age.

Ybarra was the sixth of nine children born to Alberto Ybarra, a roofer, and Maria Espino. His family moved from Villa Gonzalez Ortega in Zacatecas to Juarez when he was 3.

He was a law student at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, or UNAM, when in his sophomore year, he survived the 1968 Tlatelolco student massacre. Mexico’s armed forces fired on student demonstrators protesting the upcoming Olympics in October 1968. The number of casualties has been in dispute, but ranges in the dozens.

The terror didn’t end then for Ybarra, who was arrested a year later while trying to commemorate the event. He told family members that he was tortured while close friends were never seen again.

He eventually was released and found sanctuary in California, Autumn Ybarra said, first staying with a sister in Moorpark. Arturo Ybarra bounced around Southern California communities before settling in Watts.

His generosity for the community he would call home, “was endless,” said Ivory Parnell Chambeshi, the director of neighborhood initiatives with the mayor’s office.

For 30 years, Ybarra’s organization provided meals to hundreds of Watts and South L.A. families during the “Navidad en el Barrio” holiday giveaway, according to Chambeshi.

Few places hold as much importance in Los Angeles’ black history as Central Avenue, the birthplace of the West Coast jazz scene and a magnet for those leaving the South seeking a better life.

Around 250 families were served with two weeks of food at last year’s event, according to Chambeshi. And not just any provisions, she quipped.

“They weren’t giving away canned goods,” she said with a laugh. “Arturo insisted on quality meals, so he asked for eggs and potatoes and rice.”

While many Watts Century Latino Organization programs were tailored for Ybarra’s Latino community, he offered support to all Watts residents.

“That’s one thing that is lost,” Chambeshi said. “He helped the Latino community, but he also reached out to the Black community and really fought for everyone.”

L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn adjourned last week’s meeting in Ybarra’s honor.

“Arturo was always in the middle trying to create peace, and bring all sides together,” Hahn said. “He really was the epitome of what a community activist should be.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.