Germans. Hoosiers. Canadians! How they shaped the Southern California we know today

Southern California: a place where towns were pioneered and settled by ... communism!

Well, socialism. OK, it was really communitarianism, and at the time it seemed like a good idea.

That time was the last couple of decades of the 19th century, when many thousands of Americans — some of them starry-eyed with idealism or disgusted with the ruthless prosperities of the Gilded Age — decided to reset their lives in colonies founded on idealistic principles and an immense and often overgenerous faith in human nature.

Decades before, in the 1840s, New England transcendentalists had organized Brook Farm in Massachusetts, born from a utopian template of a community of shared labor and rewards that could also be creatively stimulating. Transcendentalism’s adherents numbered among them Louisa May Alcott, Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau.

Forty years later, the American frontier was closing, large-scale agriculture was poised to displace small farmers, industrial plutocrats named Carnegie and Rockefeller were getting stupefyingly rich as a new class of American poor emerged, and the new Statue of Liberty was welcoming immigrants whose differences from earlier Americans were creating frictions.

What better time to make a break from that — and what better place to find a clean slate for it — than California, the new, the last horizon of that vanishing frontier?

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

And so the “colonies” came to California. These colonies were in fact associations of affinity, of shared interests, communities of like-minded people — not necessarily relatives but neighbors or fellow churchgoers or the intellectually or artistically or industrially homogeneous. They struck out for California, pooled their resources and labor, bought up land and distributed or sold shares to the residents, who owned their land, pooled labor and resources, and communally owned vital assets and services such as water and electricity and even industrial facilities.

California is an enormous place, and it can swallow up even the ambitious and industrious. For people coming to this far-off Elysium from settled and rooted places points east, The Times offered this comfort, and endorsement of the colony system, in April 1888:

“When they come here and for months see no familiar face or hear any well-known voice, a feeling of longing for the old home comes over them … even if that home at the time is buried under the snows of an Arctic winter … one of the best remedies for this state of affairs is the colony system of settlement, which has become so popular in Southern California. … some of our most flourishing towns and cities, notably Anaheim, Pasadena, and Ontario, were started in this manner.”

Nine years later, The Times was even proposing Los Angeles — a city already home to a thriving French population — as the ideal place for a Parisian “colony of self-supporting artists” searching for a new home.

Railroad fare wars made it seem foolish not to go to California. Ticket prices dropped, then plunged, and finally, for a few hours on March 6, 1887, you could ride the Santa Fe from Kansas City to L.A. for just $1.

The freeways, the smog, the people, the culture, the intellect — nothing and no one is spared when it comes to people from New York and elsewhere insulting Los Angeles.

San Bernardino

But the first “colony” here arrived on wooden wagon wheels more than 35 years before then, in early 1851, just months after California became a state. It was sent from Utah by the head of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Brigham Young, to found a settlement, to cultivate “desirable fruits and products … [and] to plant the standard of salvation in every country and kingdom, city and village, on the Pacific.”

These hundreds of settlers in dozens of wagons founded San Bernardino, which was then still in Los Angeles County. (Heck, what wasn’t? For a short time, L.A. County went all the way from the Pacific Ocean to the Colorado River, and included present-day Orange and San Bernardino counties, and bits of Riverside, Ventura and Kern counties too.)

The church members were quick and efficient, which cannot be said for a lot of the future “colonies.” They bought the Lugo brothers’ ranch, constructed a road to bring lumber down from the mountains to build a fort, then a community laid out on the same rectilinear principles as Salt Lake City, whose central streets, Brigham Young decreed, should be wide enough for a team of oxen to turn around without “resorting to profanity.”

They also brought one lawless practice, and another culturally shunned one. California was a free state, and several church members had slaves with them, notably Robert Smith, who brought an enslaved woman who would gain fame — and her freedom — as Biddy Mason, who dared to go to the white men’s court and win her liberty. She would become a real estate mogul and a Black leader in L.A. And the colony’s two leaders were polygamists whose “plural wives” accompanied them to California. The colony was still expanding when, after half a dozen years here, the church members were ordered back to Utah. San Bernardino stayed on the map.

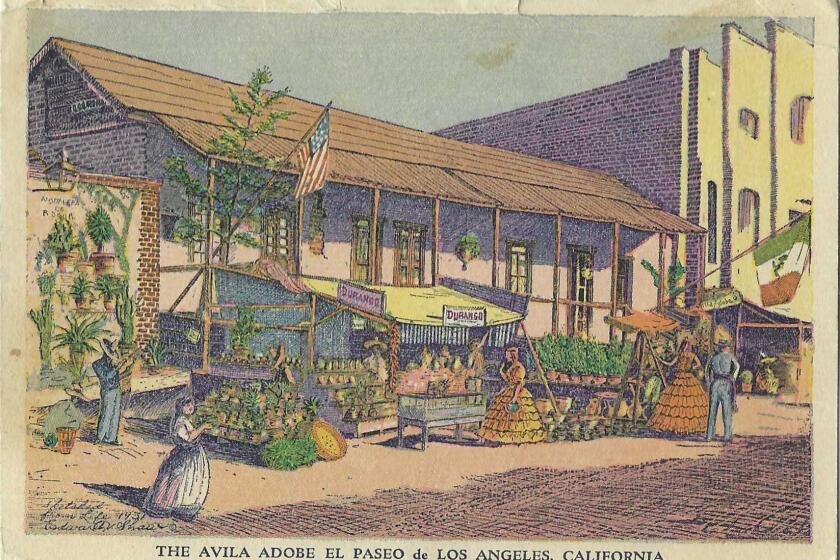

Native American settlements were first, and then the rancho system -- Spanish then Mexican land grants throughout California -- were built atop and near those settlements and still shape our geography and place names.

Pasadena

We can safely say that the Indiana Colony that became Pasadena was literally blown here. The blizzard of 1873 left snowdrifts a dozen feet high on some Indiana farms. Livestock froze and died where they stood. The temperature near Fort Wayne was recorded at 34 degrees below zero.

To hell with that, said the company of good Hoosiers, and they joined a settlement plan to buy land on the Rancho San Pascual near the Arroyo Seco. Their compact became the Southern California Orange Grove Assn.

As The Times reported more than 100 years ago, the land was divided into lots of varying size. To decide who got a chance to buy which lot, the settlement leaders held a picnic on Orange Grove Boulevard — then flanked by fields, not by millionaires’ mansions — and each man of the colony chose his preferred site. By luck and happenstance, no two of them coveted the same piece of land. They all settled happily into sunshine and citrus in the town they named Pasadena. And for an engrossing debate on how a word that supposedly means “Crown of the Valley” in the Mississippi Chippewa language wound up in Southern California, there’s this.

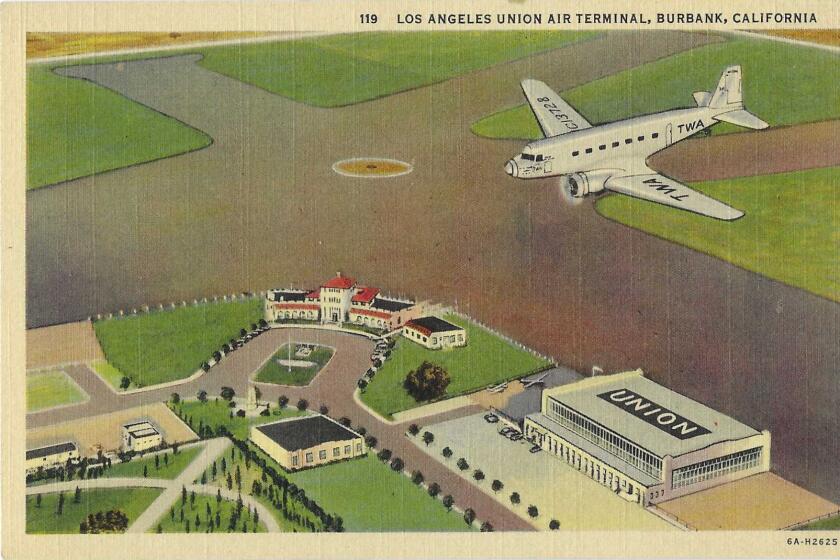

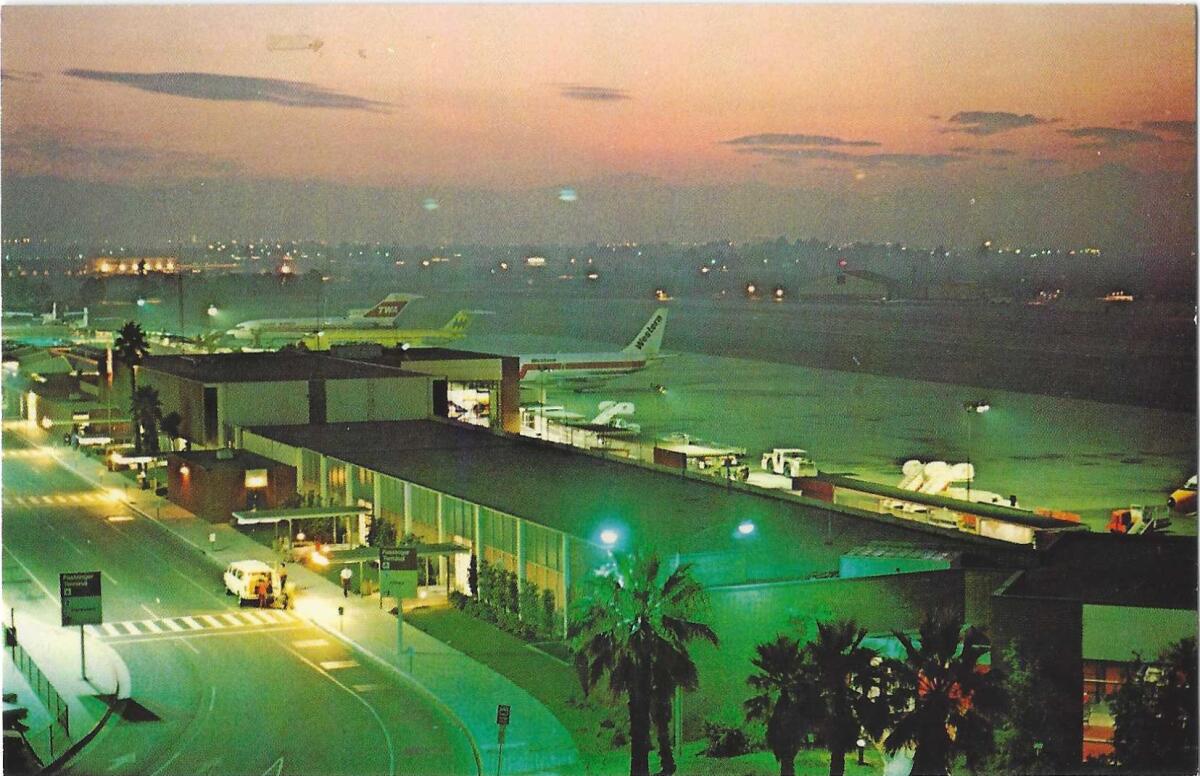

We still have lots of airfields, but gone from the landscape are the runways — near Griffith Park, near Wilshire and Western, in the Palisades — that could have challenged LAX for air superiority.

Ontario

Another model colony took another Native American name. Ontario was the vision of Canadian George Chaffey and his brothers, who bought the land in 1881 and named the place for their home province, whose name supposedly means “beautiful water” in Iroquois.

California’s beautiful water was tamed water, a community irrigation water system ideal for the gentleman farmer. Ontario’s survival and prosperity so thrived in efficient and bounteous irrigation water that in 1903 it was proclaimed a “model irrigation colony” by Congress. The brothers drew up plots of land in their model colony, inviting their fellow Canadians to come and grow oranges, and organize agricultural co-ops — the big Sunkist plant here was a going concern for about 80 years.

A model colony had to be a moral colony too. Advertising itself in a magazine in the 1890s, Ontario bragged of its six churches, flourishing Methodist college, “and best of all, no SALOONS.” Peace to the departed spirits of the Chaffey brothers: a search for “best Ontario bars” now turns up a great many in the old colony that is now a city and the home of Ontario International Airport.

BTW, Chaffey was an engineer of considerable ambition and energy, and he worked on a plan to bring his irrigation ideas to the desert miles of the Imperial Valley, and later to Owens Valley.

Anaheim

Model colonists must have come to California with dowsing rods packed in their trunks because job one was always securing water. About 50 German settlers showed up in 1857 to the future hallowed municipal ground of Disneyland, to organize the Los Angeles Vineyard Society as a wine grape-growing concern. They cleared and divvied up their 1,165 acres, bought at $2 per, to grow wine grapes, dug a 5-mile-long canal to the Santa Ana River, and set up a community water company with shared ownership stock.

The town crafted the portmanteau name Anaheim — Ana for the river, and Heim, the German word for home. After an 1870 wine pest wiped out their grapes, they pivoted to citrus.

Water and cows

In 1895, William Smythe, a water visionary in New York, planned for the National Irrigation Congress to settle a California colony for the “reclaiming of the so-called arid lands by irrigation, and, secondarily the establishment of agricultural and manufacturing communities.”

Handily for Smythe, there was an irrigation Bible verse in 2 Kings, “Thus saith the Lord, Make this valley full of ditches … ye shall not see wind, neither shall ye see rain; yet that valley shall be filled with water, that ye may drink, both ye, and your cattle, and your beasts.”

That was the Ashurst ranch, 10,000 acres in Tehama County, across the Sacramento River from Leland Stanford’s property. Colonists would collectively own municipal assets such as water, light and power franchises, but own land individually, minimum five acres. The colony, The Times wrote, believes it can solve “without socialism, free love, and other vagaries of theorists, the ideal conditions of human life and association.”

Like most colonies, Ashurst was in time beset by water problems and fluctuations of fortunes human and natural. By 1906, there was so little call for the colony school that it was absorbed into another district. As the Pine Bluff News reported then, another nearby school district had also failed “on account of too much ‘race suicide’ in the vicinity,” which presumably meant a low birth rate among whites. It probably need not be said that these utopian colonies were almost exclusively white.

At least half a dozen colonies arose in the 1870s and ‘80s in Fresno County, including the Scandinavian Home Colony, the Washington Irrigated Colony and the Italian Swiss Colony — the adorably lederhosed TV commercial winemakers, who soldiered on until the late 1980s.

Right here in Los Angeles County, the Cooperative Colony, after much hemming and hawing, finally settled in 1887 on buying land between Compton and Gardena for a cooperative that they called — officially — Clearwater, but unofficially, “the milk shed of Los Angeles.” At one time, 25,000 dairy cows supposedly mashed into a single square mile. In 1948, Clearwater and its neighbor dairy town, Hynes, kissed and made up and became Paramount.

Who is Griffith Park named for? What about Vasquez Rocks? The Broad? Mt. Baldy? Here are the namesakes of L.A.’s best-known landmarks.

Elsewhere in Orange County

The shortest-lived but most romantic colony was established for Polish artists and musicians in Santiago Canyon in Orange County. Their founder was the classical Polish actress Helena Modjeska, whose specialty was Shakespeare.

She dreamed up her Forest of Arden as a working retreat for her Polish friends, among them future Nobel novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz, author of “Quo Vadis.”

Her description of it — and what came of it — was as poetical and fulsome as her stage roles. The rustic utopia would be a place where they could “bleach linens at the brook like the maidens of Homer’s ‘Iliad’! After the day of toil, to play guitar and sing by moonlight.…”

Her 200 horses had the names of Shakespeare characters, and in 1895, the Santa Fe railroad renamed its closest train station Modjeska in her honor.

The colonists, as The Times noted years later, packed not the tools of farm life but paintings and books. On the first day, Modjeska trilled that her compatriots were “anticipating great joy from the touch of Mother Earth.” Soon, too soon, it was instead, Ow, my back, or, I have to write 2,000 words today or my publisher will kill me.

She told the Philadelphia Press in 1897 that “our idea of a Polish colony was only a sentimental one. The experience was very costly, and we were not a success as farmers.” The experiment broke up after six months, and most everyone left for home. Modjeska returned to the stage while her husband stayed on there, in the cottage designed by renowned architect Stanford White, and actually made a pretty good “go” of the Forest of Arden, tripling the acreage and profitably growing olives and raising cattle, before his wife sold it in 1906.

Some miles away in Orange County, a temperance colony named Westminster was organized in 1870 by a Presbyterian pastor and named for an earlier English set of church tenets. Alcohol would be permitted only for “sanitary or scientific purposes.” Colonists too shared control of water, and raised dairy cattle for milk, which was wise because settlers would not even grow grapes lest they be used for wine. When a saloon dared to open its doors, it soon closed again for want of business. This was the beginnings of the city of Westminster.

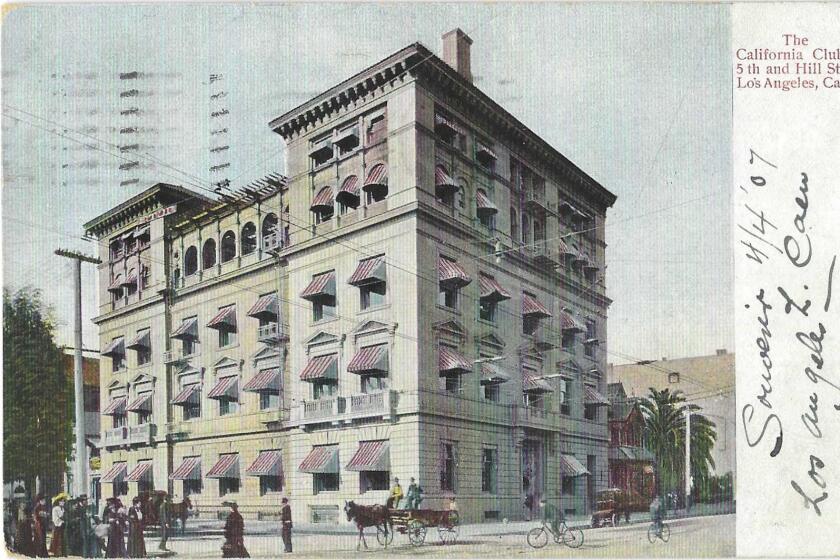

An L.A. Times exposé — and in one instance, Gloria Allred quite literally exposing sex discrimination — led the Jonathan Club, the California Club, the Friars Club and others to become less exclusive, if not less expensive.

And some failed

Six months before the start of World War I, Benjamin Brown, an organizer of a Utah Jewish colony named Clarion, announced that many Jewish Angelenos supported a larger colony movement for Jews. “The Jew is just as efficient in farming as in the mercantile life,” and 63% of American Jews “are now working in sweatshops with little hope of betterment as long as they remain in crowded cities.”

A year before, the American Israelite newspaper had reported rumors that a Jewish colony in Colorado was facing “dire failure,” and singled out the problem: The economies of scale that were a plus for the colonies were being swallowed up by larger economies on a larger scale. “The small farmer in the West is being crowded to the wall in very much the same fashion that the small tradesman in the city is being driven out by the great department stores. Vast tracts of land are cultivated and the product harvested by machinery … against this, human labor cannot compete.”

And the national financial panic of 1893, which lasted several years, was walloping small farmers with nosediving crop prices at a time when U.S. business was cohering into ever more powerful monopolies run by Gilded Age plutocrats with names such as Carnegie and Rockefeller.

The soil of California is quite truly strewn with the phantom bones of failed colonies, some dreamed up as a paradise of ideal humanity, others crafted more or less cynically.

If there was a stereotype of a failed 19th century California utopian colony, it has got to be the Kaweah colony, among the sequoia forests of Tulare County.

Begun in 1886, its co-founder, a native Californian named Burnette Haskell, was an ardent radical who imagined a colony of thoughtful, hard-working activists waiting until their “cooperative commonwealth” model would take the place of overthrown capitalism. Then, “step would follow step until we should have established justice and abolished alike the tramp and the millionaire.”

On a practical note, the colony planned to support itself with logging the sequoias. The giant sequoia we now know as the General Sherman, the world’s largest tree, Haskell named the “Karl Marx tree,” after his hero, author of “The Communist Manifesto.”

For a time the colony worked. Colonists built roads into the forests, dug irrigation canals, grew crops, organized an orchestra, a school, a library and a general store, poetry discussion groups and lectures. Visitors came from as far away as Europe to see utopia at work.

But then the cracks appeared. In 1913, Arthur Wesley Johns wrote a thesis about the dead-and-gone Kaweah for his Stanford master’s degree. The colonists, in an echo of the Declaration of Independence, pledged “their fortunes, their honor, their lives” to the cause. But what cause? Kaweah failed in part, Johns wrote, because it was “not homogeneous … there was no central, binding ideal … to bind the Kaweans together.” The place was populated by Marxists and anarchists, “churchmen and agnostics, freethinkers, Darwinists and spiritualists … and dress reform cranks.” The women even played baseball.

In a deliberately flattened hierarchy, no one seemed to be in charge. The discussions were endless and intense and rarely resolved. In short, Kaweah sounds like the homeowners association board meeting from hell.

It was already on the verge of breaking up when the federal government in 1890 established Sequoia National Park and vacated the colonists’ claims. By 1892, The Times wrote, the last of them had gone.

The Great War put an end to most of these great experiments. In the 20th century in California, perhaps only the Llano del Rio colony near Palmdale even gave it a try. It was founded by the socialist politician Job Harriman, and it began just a couple of months before World War I and ended the year that war ended. It too was plagued by isolation and unreliable water sources.

True to form, the conservative Times missed no opportunity for we-told-you-sos, including this lofty homily: “It should be remembered that while cooperation is a good servant, it may, under certain circumstances, become a very hard taskmaster.”

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.