$600,000 in stolen wine: Inside one of California’s biggest high-end alcohol heists

Security camera footage from Lincoln Fine Wines shows the June 30 theft of hundreds of bottles of wine and spirits from the Venice shop.

The masked man dropped down into darkness, the light from his mobile phone illuminating the bottles that lined the cellar walls of Lincoln Fine Wines.

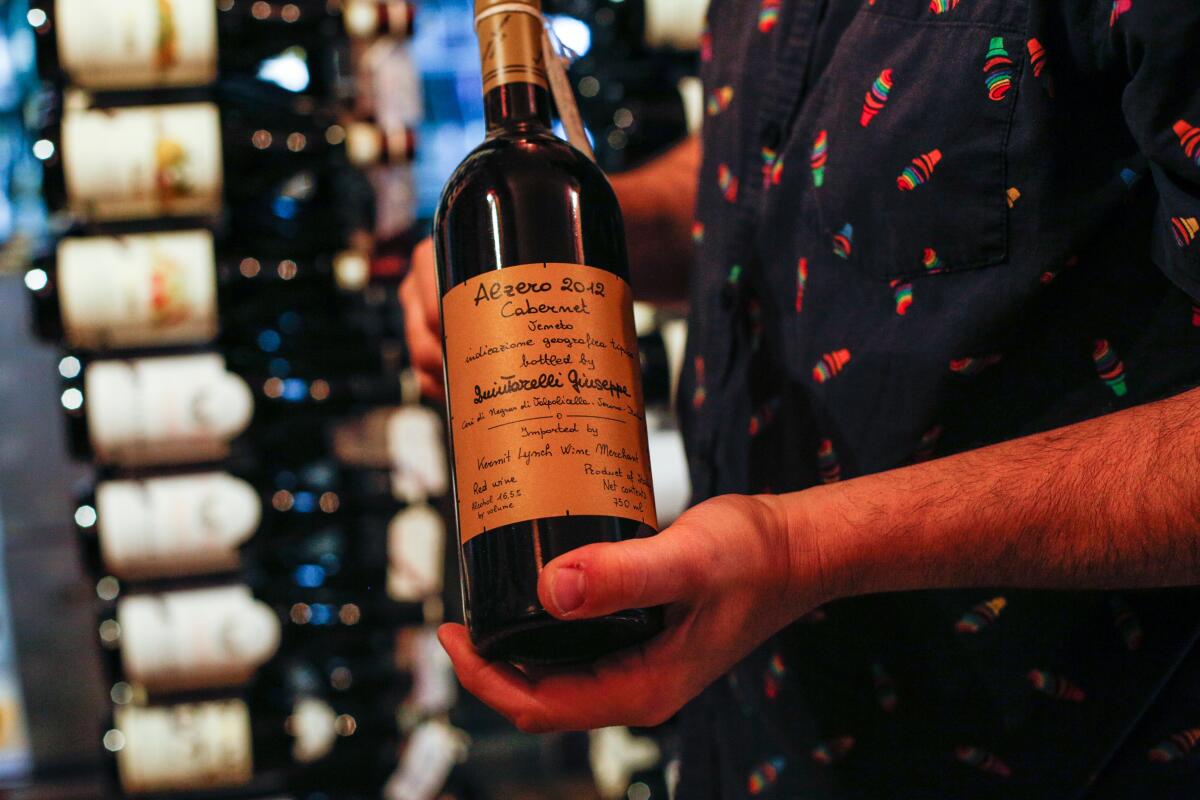

2001 Sine Qua Non “On Your Toes” Syrah. 2006 Chateau d’Yquem Sauternes. 2009 Chateau Mouton Rothschild Pauillac. 2012 Giuseppe Quintarelli Amarone della Valpolicella.

The climate-controlled cellar housed the Venice store’s priciest vintages. There were about 1,500 bottles — mostly French, Italian and California wines that had taken decades to assemble.

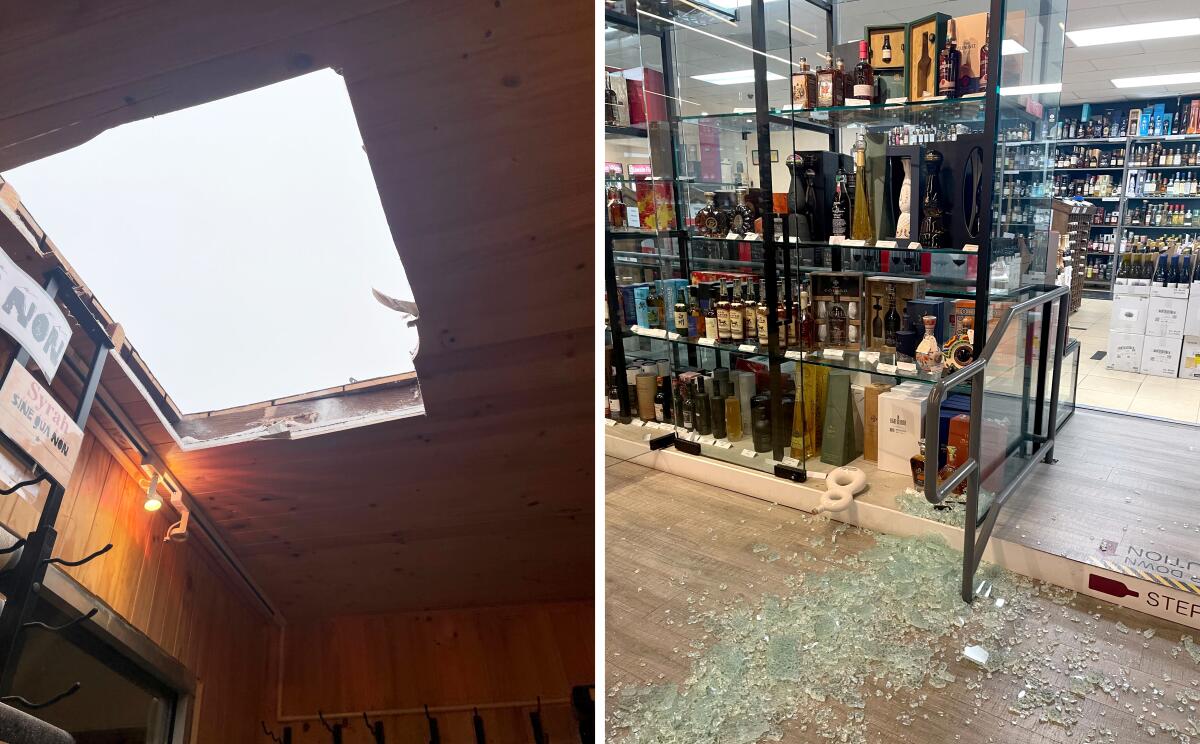

It was after midnight on June 30. The store was closed, its security system activated. But this man had gained access to the trove without setting off the alarm. He did so unconventionally: by cutting a hole in the roof above the cellar.

The thief — who dressed in black and wore a red-billed baseball cap — worked efficiently, deftly moving among the crates and racks to gather up much of the choicest wine. He kept his phone in hand, training its light on the bottles, which featured handwritten price tags, and occasionally raising it to his ear.

In about 3½ hours, the burglar managed to commit one of the biggest California wine crimes in memory, making off with about 800 bottles — a haul worth around $600,000.

The stolen items included about 75 bottles that retailed for upward of $1,000. Among them were rarities such as a bottle of Billecart-Salmon Brut Reserve Champagne in an uncommonly large, 15-liter format known as a Nebuchadnezzar. Some of the selections, wine consultant Melissa Smith said, are “very, very hard to find.”

“This is an extraordinary list,” added Smith, founder of Enotrias Elite Sommelier Services. “A lot of them are things collectors would want in their possession.”

According to Los Angeles Police Department Det. Joel Twycross, the thief had at least one collaborator, a person who was “reaching down from the rooftop” to take the bottles from him. And there may have been as many as two other accomplices helping him steal the booty, which also included some hard liquor.

“We suspect there may be a person that is getting the wine handed down to them off the rooftop and possibly a getaway driver,” Twycross said. “It is evident that this was planned for a while and a lot of effort was put into mapping out how to evade getting caught.”

Around 3:45 a.m., the thief — who wore a sweatshirt from L.A. streetwear brand Anti Social Social Club — exited the cellar and hurried toward a glass display case near the center of the store. It housed high-end bottles of Scotch, bourbon and other alcohol. He shattered a pane and pillaged the display. By then, the burglar had tripped Lincoln Fine Wines’ motion sensors, triggering an alarm. After several excursions to and from the shop’s main floor, he returned to the cellar, climbed up a stack of wooden boxes and departed via the hole in the ceiling.

The crime, the latest of several high-profile wine thefts in California over the last decade, unfolded in surveillance videos captured by multiple cameras installed at the shop. Lincoln Fine Wines’ longtime owner, Nazmul Haque Helal, provided the footage to The Times, along with a list of the stolen inventory. Some of the videos offer a grainy but almost complete view of the thief’s efforts. In others, however, the picture has been fully obscured by the burglar, who, after emerging from a white pickup truck parked on a neighboring street, disabled a handful of exterior and interior cameras before beginning his spree.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Twycross said that the thieves likely knew what they planned to take. Helal agreed, noting that the intruder passed over many expensive bottles of California wine to take ones from France. Nearly 400 of those came from what are arguably the country’s two most storied winemaking regions: Bordeaux and Burgundy.

Could this emphasis reflect a connoisseur’s palate? Helal and the private investigator he has hired to work the case both believe that the choices made by the thief reveal a knowledge of wine and the market for it. But not necessarily his own expertise.

“They showed an incredible amount of savvy in terms of the choices that they made,” said private eye Bruce Robertson, who is president of L.A.-based Tristar Investigation and also collects wine. “But I don’t for a minute think that the people who were on the ground were the masterminds of this. You just wouldn’t have that kind of knowledge on the ground, and the guy was on the phone. He was obviously consulting with somebody.”

Meanwhile, as the LAPD’s investigation continues, and Lincoln Fine Wines tries to move forward, a question has been reverberating across Southern California’s wine scene at dinner parties and in WhatsApp group chats.

How exactly will the thieves turn all those stolen bottles into profit? And how do you locate loot that can be sipped — say a $2,400 bottle of Domaine Francois Raveneau Chablis Grand Cru Les Clos — into intoxicating oblivion?

Selling stolen merchandise

Tracking down pilfered wine isn’t easy.

There have been successes — investigators recovered most of a $500,000-plus cache of wine stolen from the French Laundry restaurant in Napa Valley in 2014. But in several other cases, authorities arrested the perpetrators but never found the wine.

Twycross said that, unlike other sought-after valuables such as gems and watches, wine bottles typically lack serial numbers. Only some brands, such as Domaine de la Romanée-Conti — whose vintages are widely viewed as among the best in the world — include identification numbers.

Helal, who is offering a $10,000 reward for information that leads to an arrest, said that customers have been sharing their perspective on the whereabouts of his Lincoln Boulevard store’s purloined inventory.

“They say it is overseas,” Helal said. “They said [the thieves] will be hiding one or two months and then they’re going to come out.”

Diana Hirst, chief executive of Hi-Time Wine Cellars in Costa Mesa, had a similar perspective.

“With the level of sophistication shown,” she said, “I would imagine there were buyers lined up and the bottles are probably overseas already.”

Wine industry experts said that thieves could also decide to slowly unload the stolen goods — perhaps even locally — selling bottles one at a time or in small groups to retail shops or consigning them to auction houses.

Carlsbad-based wine merchant Max Kogod, who reviewed a list of the stolen wines at The Times’ request, said that many of the bottles, while expensive, were vintages easily obtained at any number of retailers. That ubiquity, he said, would make it easy for thieves to reintroduce much of the wine to the marketplace, little by little, without detection.

“In general, when I see these, I would never think I’d be looking at a stolen bottle,” Kogod said.

The $300,000 worth of wine that was stolen from the French Laundry restaurant on Christmas Day has turned up — in Greensboro, N.C.

On the other hand, David Othenin-Girard, spirits buyer at K&L Wine Merchants, which has its own online auction platform, said that retailers and auction houses that are offered a substantial collection of wine would be vigilant and suspicious.

“The regular questions when someone comes in with a large cellar are, ‘Where has this been stored and where did you purchase these? Show us the provenance of these bottles,’” said Othenin-Girard. “If it’s someone who says, ‘Uh, well, I had it in my uncle’s cellar,’ that’s a big red flag. Not only because it could be stolen; if it’s wine that hasn’t been stored properly, we could be selling vinegar.”

Ryan Curry, co-founder of Santa Ana-based wine merchant Golden 8 Wines, cautioned that the criminals may not “be getting top dollar for their loot.” He explained that wine sold on the legitimate resale market can trade for as little as half its retail price.

“Now if you’re trying to move stolen goods to people that know they are buying stolen goods, I imagine the prices realized would be significantly lower,” Curry said.

The same rule would apply to the hard liquor taken in the heist. Though only a handful of bottles of spirits were stolen, they were pricey. Among them were a 1971 Last Drop blended Scotch that costs about $3,700 and a Remy Martin Louis XIII Cognac that goes for about $4,400.

Othenin-Girard guessed where the Remy Martin might eventually end up: “You could flip that to a club.”

It has been Lincoln Fine Wines manager Nick Martinelle’s job to catalog the stolen inventory — and it has been painful.

“It isn’t just about the price,” he said. “Inside that bottle is a work of art, a unique thing that will never be replicated because wine is a living, breathing thing.”

He’s clinging to hope that the wine will be found and returned to the store. And that the people who stole it will be busted.

“The blood, sweat and tears that went into these bottles ... to see them taken, for us at the store, it was a violation,” Martinelle said. “I don’t want it to happen to other people.”

A history of wine crimes

Wine thieves have run rampant through Southern California shops and wineries over the last few years.

In 2017, for example, Robert Henry Blalock Jr. was charged in connection with two thefts from Santa Ana’s Wine Exchange. In all, he stole bottles worth tens of thousands of dollars, including a rare vintage of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti valued at $30,000.

Several victims of wine thefts were loath to talk about what they had endured. Representatives of four wineries and one shop that had been burglarized over the last half-decade or so either declined to comment for this story or did not respond to interview requests.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The owner of an Orange County wine shop that was burgled in May explained that it made little sense to publicize her ordeal. Doing so, she said, risked putting her business on the “radar” of thieves and sending them a message of “come rob us.”

“I want this to go away, for us to be low key, not to advertise we have expensive wines and faulty security,” said the merchant, who requested anonymity.

Sometimes the thefts are about as inside as an inside job can get: Over a four-year period ending in 2012, George Osumi, the operator of Irvine’s Legend Cellars, stole bottles worth $2.7 million by swapping out customers’ prized vintages with lower-cost knockoffs. After netting nearly $600,000 via sales of the ill-gotten alcohol, Osumi was caught and given a six-year prison sentence in 2013.

One aspect that made the Lincoln Fine Wines burglary unique — at least among wine thefts — was the mode of entry. Until now, Southland rooftop break-ins have largely targeted banks or were reserved for heists of non-quaffable valuables. (Think: diamonds.)

A bar two miles south of Lincoln Fine Wines also recently suffered an audacious rooftop break-in that led to the loss of thousands of dollars of alcohol.

In October, a man entered Baja Cantina after hours by climbing through a skylight, according to Rum Raiders, a liquor news website. But that’s where the similarities to the wine heist end. Instead of absconding with top-shelf bottles of booze, the man drank them on site. Surveillance video showed the intruder swigging Don Julio tequila and other alcohol.

Eventually, he passed out, the website said, making it easy for law enforcement to arrest him the next day.

The shop moves forward

On a July 15 visit to Lincoln Fine Wines, a longtime customer from the Pacific Palisades popped in with his son and immediately approached Helal.

“I’m so sorry this happened to you,” said the man, a pained look on his face.

Helal, who remarked on how tall the boy had grown, told the father that many of the usual sort of wines he’d select from the cellar had been stolen.

“That’s OK — I’ll find other ones,” the shopper said with a smile.

Helal, who opened Lincoln Fine Wines in 2008, said he has been comforted by the support of regular patrons. And the hole in the cellar’s ceiling — the most obvious physical reminder of the crime — has been sealed.

But, more than three weeks after the crime, the store was still going through its inventory and discovering bottles that had been taken.

And Helal has been thinking about an unknown man who visited the shop about six weeks ago and was “taking a lot of pictures,” including of the glass display case that housed expensive spirits. Given that the thief cut into the ceiling directly above the cellar — and swiftly disabled several security cameras — Helal surmised that the criminals must have cased the store ahead of the burglary.

“When I saw he didn’t buy anything — just took the pictures and left — I felt a little bit odd,” said Helal, who noted that he doesn’t have footage of the man because his security system records over surveillance video after 12 days.

For police detectives, it’ll be a tricky investigation.

In the video footage, for example, no license plate can be seen on the truck used by the criminals, Twycross said. He added that the LAPD is continuing to collect security camera recordings from the surrounding area in the hope of getting a better look at the vehicle or the thieves.

Helal believes the crime was aided by the knowledge of an oenophile, but he’s confounded by some of the choices made by the thief. He wondered why the man took two expensive bottles of Krug Champagne — a rare 2012 vintage that sells for about $3,400 — but ignored other similarly priced ones from the brand. Instead, the thief stole a bottle of Guillaume S. Selosse Champagne that sells for about $800.

“Selosse is a Champagne that not that many people know — only wine people would,” he said. “We had Krug — they didn’t take it, those are over $3,000. I am kind of confused.”

Was the heist the work of a Selosse aficionado? Or did that bubbly make it into the pickup truck — with some of the pricey Krug spared — simply because the thief was working quickly in the dark? Industry experts were split on the matter. But three of them agreed that the oversized bottle of Billecart-Salmon Champagne that was also stolen ranked among the most notable pilfered items.

The Champagne was not the finest wine taken in the heist. But its unusual size makes it quite rare. A spokeswoman for Billecart-Salmon said that only eight to 10 of the 15-liter bottles are imported to California annually.

“If you’re going to show off,” Kogod said, “that would be the one to show off.”

The large-format offering — equivalent to 20 standard bottles — is so unusual that a discerning wine shop would likely be suspicious if, in the aftermath of the widely publicized crime, it were presented with the chance to buy one, experts said. In light of that, Smith and Kogod said they imagined that the thieves might instead opt to do something else with the nearly 85-pound Nebuchadnezzar.

Pop it.

“That,” said Smith, “would be a celebration bottle.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.