Column: A massive borrowing binge is brewing in Sacramento

SACRAMENTO — Left to their individual desires, California legislators would go on a massive borrowing binge.

They’d sell bonds to fund ambitious projects such as housing and treating homeless people who are mentally ill, controlling floods and updating classrooms — all worthy projects.

But should they be paid for with borrowed money that, with interest, roughly doubles the projects’ cost? Or should they be financed with cash out of the state banking account, the general fund?

There are sound arguments for both.

Bond financing is like taking out a home mortgage. It’s the rare homeowner who can pay cash for a house. A mortgage makes economic sense because the benefits of homeownership continue year after year. They’re not confined to the year of purchase.

But you don’t take out a mortgage to buy groceries or pay the cable TV bill.

Some projects on legislators’ wish lists fit more realistically into the grocery bag.

Here’s an example of the opposition bond backers will face when their proposals are debated in the Capitol next month and eventually hit the ballot:

“Why is a bond — any bond — necessary?” asks Jon Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Assn., named after the anti-tax crusader who sponsored the landmark Proposition 13 in 1978 that substantially cut property taxes.

“Despite a drop-off in state tax collections, California continues to produce massive amounts of tax revenue from the highest-in-the-nation income tax rate, highest state sales tax rate and highest gas tax,” he says. “Taking on further debt makes little sense.”

He adds that “borrowing costs today are higher than they have been in years,” and that “while Wall Street bond brokers and bond holders will profit from more California debt, voters have to decide if it is in California’s best interest.”

Yes, fortunately, after Gov. Gavin Newsom and legislative leaders sort it all out, California voters will have the final say on what merits borrowing and what doesn’t. They’ll decide on state ballots during the March primary and November general election next year.

In their dream world, lawmakers have introduced roughly a dozen bond proposals totaling more than $100 billion. Some overlap. Some will be combined. Some will be discarded and not make the cut.

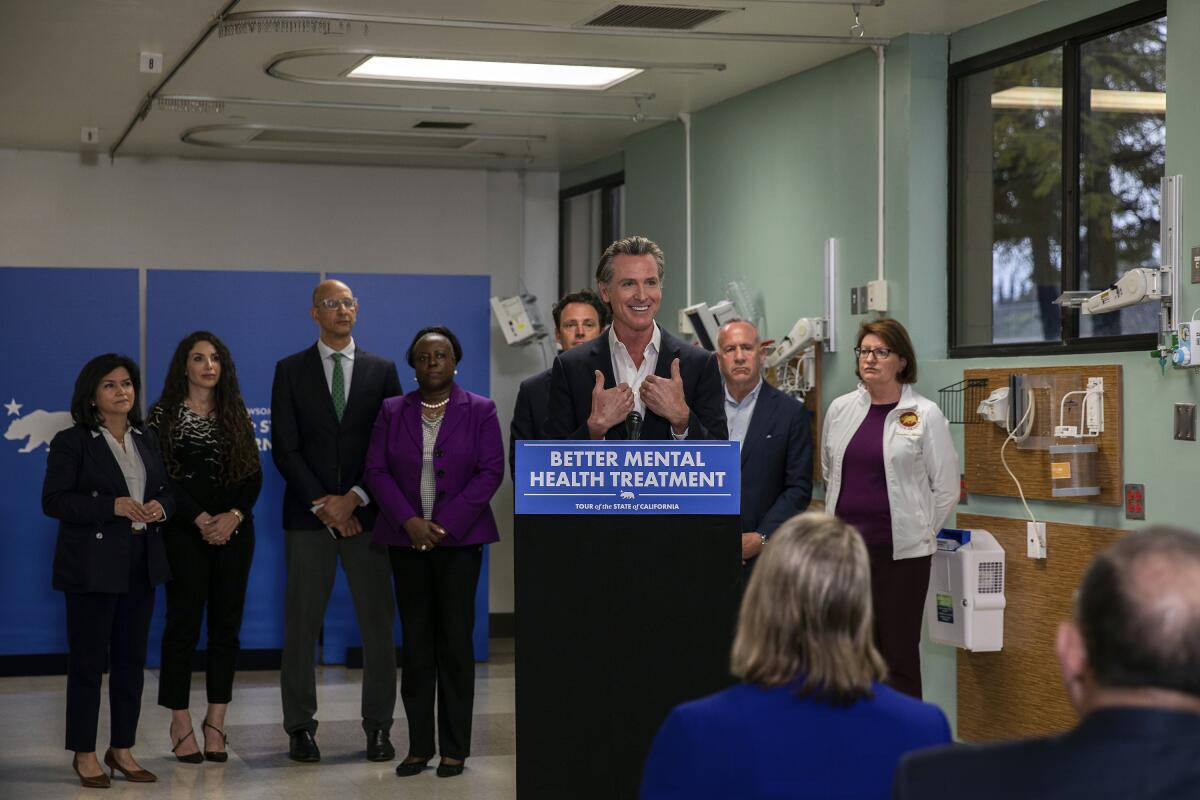

Gov. Gavin Newsom calls for sweeping mental health reforms to generate billions for behavioral health facilities throughout California.

Newsom and legislative leaders — when they finally seriously engage in negotiations — will whittle down the total borrowing to a more voter-salable figure of between $20 billion and $30 billion. It will still likely be a new record for state borrowing — if voters approve.

One thing that hovers over the lawmakers’ borrowing decisions is what’s called the state’s debt-service ratio. Experts say the annual payment on bond debt should not exceed 6% of general fund revenue. It did each year between 2009 and 2017, when Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger and Democrat Jerry Brown were governors and the state was either suffering or recovering from the Great Recession.

Currently, the state is in good fiscal shape with its debt-service ratio. It’s about 3.9%. It’s spending roughly $8 billion on bonds out of $209 billion in general fund revenue, according to the state Finance Department.

“That doesn’t mean we should pass future bonds with reckless abandon,” notes department spokesman H.D. Palmer.

Currently, the state is paying down about $71 billion in general obligation bond debt — borrowing for which all California taxpayers are responsible. Voters have authorized an additional $25 billion in bonds that haven’t been sold.

One reason for the legislators’ rush on borrowing is that California’s problems are many — the governor himself constantly highlights them — but cash is scarce, despite a $311-billion budget.

The governor and Legislature projected a $32-billion revenue shortfall before settling on their spending plan for this fiscal year. And smaller deficits are forecast for the next three years.

But as state Sen. Steve Glazer, a moderate Democrat from Contra Costa County, wrote in a recent op-ed for The Times, this year’s budget is “dedicating spending to getting homeless people off the street, supporting schools, keeping public transit afloat and treating mental illness.”

“But … we’ve already spent billions of dollars on the same problems — with very little to show for it,” he said, adding: “Our failures are evidence that good intentions and lots of money are not enough to fix what ails the Golden State. ... the Legislature must ensure that the money we spend is actually improving the lives of the people.”

Bay Area legislator Steve Glazer argues that the Legislature and Gov. Gavin Newsom keep spending more on issues that can’t be solved by money alone.

Veteran Democratic political consultant Gale Kaufman, who has managed several ballot measure campaigns, told me: “Homelessness is the most important issue in polls. But that doesn’t sell a bond. Billions have gone out so far, and people don’t see a whole lot of improvement.”

Her point: Just because people are concerned about homelessness, climate change, public schools, affordable housing and fentanyl — all subjects of proposed bond borrowing — it doesn’t mean voters are going to pop for spending more money.

Newsom’s pet bond proposal would authorize $4.7 billion for housing 10,000 homeless people with mental illnesses and treating their ailments. And he’s trying to limit the March presidential primary ballot to just one bond: his.

That goes against the grain of conventional political thinking. Ordinarily, a Democrat would avoid putting a measure on a ballot when voter turnout is expected to skew toward Republicans due to a competitive GOP presidential primary.

But Newsom and his political strategists feel that voters of all ideological stripes are so fed up with homelessness that they’ll vote for his measure.

“This is an issue that’s important to voters, and getting it done sooner rather than later is important,” says Mark Ghaly, secretary of the state Health and Human Services Agency. “There’s a six-month implementation timeline.”

To qualify for the March ballot, the Legislature must pass Newsom’s bond before it adjourns in mid-September.

All bonds require a two-thirds majority vote. It would be a shock — and an embarrassment for Newsom — if Democrats didn’t line up behind the governor and approve the bond.

Newsom and the Legislature can vacillate until next spring to negotiate a bond package for the November ballot.

Then voters should be aware and read the fine print.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.