Stanford president stepping down amid scrutiny over his research

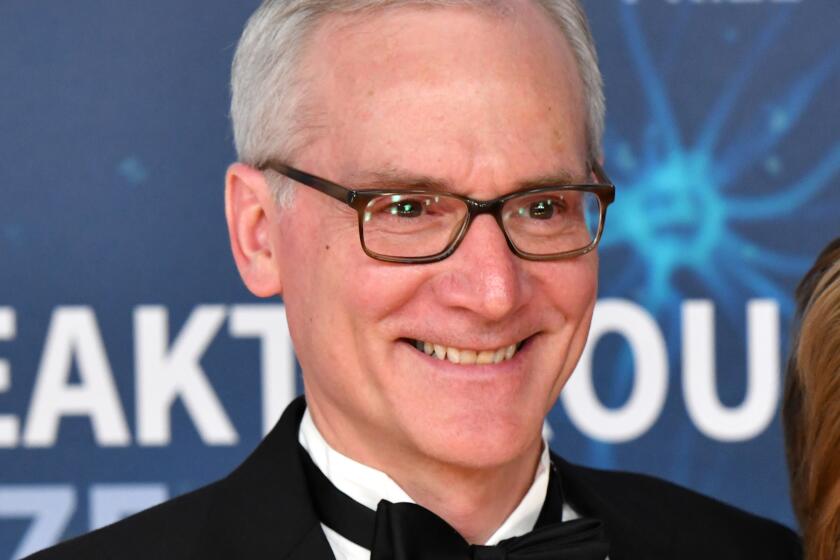

Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne announced Wednesday that he is resigning as head of the university after an independent panel determined that he failed on multiple occasions to correct errors in his published research and oversaw labs with a disquieting tendency to produce manipulated data and sloppy science.

In a lengthy report, the panel concluded that Tessier-Lavigne “did not personally engage in research misconduct” in the 12 papers it was tasked with reviewing. However, the panel did find that several of the papers included data that had been manipulated, probably without his knowledge.

“The Panel did not find evidence to conclude that Dr. Tessier-Lavigne engaged in, directed, or knew of the misconduct when it occurred, and the misconduct was of such a nature that a scientist exercising reasonable care could not have been expected to have detected it at the time,” the panel members wrote.

Tessier-Lavigne, a neuroscientist and biotech entrepreneur widely known for his Alzheimer’s research, emphasized in a statement to the Stanford community that the investigation backed his assertion that “I have never submitted a scientific paper without firmly believing that the data were correct and accurately presented.”

“Although the report clearly refutes the allegations of fraud and misconduct that were made against me,” he added, “for the good of the University, I have made the decision to step down as President effective August 31.”

Scientific papers co-authored by Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne are being reviewed following concerns that images they contain may have been altered.

Richard Saller, a Stanford professor of classics and European history and former provost at the University of Chicago, will serve as interim president beginning Sept. 1, Jerry Yang, chair of the Stanford Board of Trustees, said in a statement. Tessier-Lavigne will remain at the university as a professor of biology.

“In light of the report and its impact on his ability to lead Stanford, the Board decided to accept President Tessier-Lavigne’s resignation and agrees with him that it is in the University’s best interests,” Yang wrote.

In addition to vacating the presidency of the university he has led since 2016, Tessier-Lavigne said he will retract three papers on which he is named as principal author and issue corrections on two others.

“Stepping down as president — especially for Stanford — is a very big step,” said Debora Weber-Wulff, a professor of media and computer science at HTW Berlin’s University of Applied Sciences in Germany who specializes in detecting academic misconduct. “I do think it is the correct thing to do.”

The chain of events that led to Tessier-Lavigne’s resignation began in November, when an article detailing problems with some of his published research appeared in the Stanford Daily, the student newspaper.

As part of that investigation, the student newspaper contacted Elisabeth Bik, a microbiologist who works as an independent science-integrity consultant. Several studies that listed Tessier-Lavigne as a co-author contained “serious problems,” Bik told the Daily at the time, some of which appeared to have “an intention to mislead.”

New study suggests that people with a specific version of a particular gene who got COVID were far more likely to experience an asymptomatic infection.

Tessier-Lavigne denied committing any academic impropriety. A month later, Stanford tapped former federal Judge Mark Filip and his law firm, Kirkland & Ellis, to head a special committee to investigate the allegations surrounding his work.

Filip convened an independent panel of five high-profile scientists, including the former president of Princeton University and a Nobel laureate. They met with interview subjects more than 50 times — including at least seven times with Tessier-Lavigne — and reviewed more than 50,000 documents and digital copies of Tessier-Lavigne’s records.

The panel focused on 12 of more than 200 research papers Tessier-Lavigne has authored in his career, several of which “exhibit manipulation of research data,” according to the report.

On seven of the 12 papers he was a “non-principal author,” a more secondary role. As such, he was not directly involved in gathering or analyzing the disputed figures, the report found, “and was not in a position where a reasonable scientist would be expected to have detected any such misconduct” in its presentation.

The five papers on which he was primary author had “serious flaws” in the presentation of their data, and in four of them, data appeared to have been tampered with, the report found.

The panel found no evidence that Tessier-Lavigne was aware of these problems before publication, nor that he was reckless in allowing the papers to go out under his name.

Yet when significant problems with his published research were brought to his attention — sometimes within mere weeks of publication — the panel found that Tessier-Lavigne failed to decisively and forthrightly correct mistakes in the scientific record on multiple occasions.

“Timely correction or retraction and/or more forthright and transparent actions toward correcting the scientific record would have better served science and all concerned,” the panel found.

Furthermore, throughout his career in academia and the private sector, the laboratories Tessier-Lavigne ran had “unusual frequency of manipulation of research data and/or substandard scientific practices from different people, at different times, and in labs at different institutions,” the report concluded.

New research shows another experimental Alzheimer’s drug can modestly slow patients’ inevitable worsening — by about four to seven months — but comes with safety risks.

Before he became Stanford’s president, Tessier-Lavigne served as president of Rockefeller University in New York, oversaw the development of cancer drugs as chief scientific officer at Genentech, and co-founded the biotech company Renovis. His first faculty position was at UC San Francisco.

“As president of the university, there’s an expectation that he really sets the tone for standards of excellence and integrity in every way,” said Dr. Ferric Fang, a clinician-scientist at the University of Washington and journal editor who has investigated the prevalence of lax research standards. “I think he’s making the right decision, because he’s been damaged in terms of his ability to serve as an example and his ability to direct others in terms of standards that are expected of them.”

A principal, or senior, author on a research paper is essentially taking responsibility for the work presented in the paper, even if they did not personally perform the research, Fang explained.

“Whether they make innocent, honest mistakes or dishonest mistakes,” he said, “the principal author is responsible.”

Times staff writer Christopher Goffard contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.