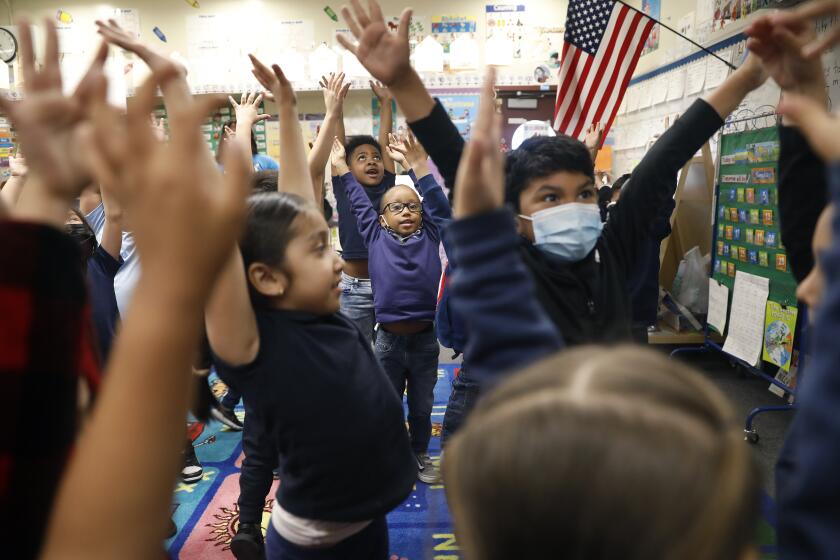

California’s hottest new student recruits? 4-year-olds

Hundreds of school banners, bus bench promos and billboards, not to mention high-volume text and robo-call campaigns, are inundating parents of California’s youngest students this summer as 4-year-olds have suddenly become the hottest recruits in California.

Last year’s lackluster launch of the state’s free transitional kindergarten expansion has propelled school districts into high gear this summer, ramping up efforts to entice the families of California’s estimated 449,070 4-year-olds to enroll their children in public schools.

The opening of this new grade level has spurred seismic shifts in the state’s complex childcare landscape — and leading up to fall school reopenings, intense competition for the state’s youngest students has erupted between public school districts and the day-care industry.

“If I were a 4-year-old, I would ask for a signing bonus,” said Bruce Fuller, a UC Berkeley professor of education and public policy.

For day-care businesses, the loss of their most lucrative children represents an existential threat because their operations often depend on collecting tuition from more 4-year-olds to subsidize losses from fewer but costlier and resource-needy toddlers and babies.

For school districts, TK, as transitional kindergarten is commonly called, is an opportunity to offer high-quality preschool, which research shows can give children a significant boost in the early years.

But public schools also see the 4-year-old population as an opportunity to increase enrollment after years of declines. Educators are hoping children who sign up for public TK will stay for the duration of elementary school, instead of leaving for charter or private schools, and help stabilize funding.

The narrative of child care in the U.S. is one of scarcity — an inadequate supply of affordable care for the nation’s youngest children. But in California, TK is alleviating one sector of the crisis. Affordable infant and toddler care remains costly and difficult to find. But because of the state’s investment in universal preschool, there is now an overabundance of options for 4-year-olds: community-based day care, Head Start, the California State Preschool Program and TK, all competing for the same pool of children.

“It’s ironic, because not long ago the problem is that we didn’t have enough,” said Pedro Noguera, dean of the USC Rossier School of Education. “We’ve begun to make it more widely available, which is a good thing, but we need to make sure it’s done efficiently.”

Amid the publicity blitz, confused parents are sorting through the noise as they select the best option for their children and families. At its core, the TK expansion will be a major financial relief for many. In Los Angeles, sending a preschool-age child to a child-care center costs parents 17.3% of median family income, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

As California expands access to transitional kindergarten for all 4-year-olds, districts across the state struggle to recruit and accommodate young learners.

“I do feel like I’m being pulled in two directions,” said Rachel Granin, a mother in Granada Hills. Granin could save $1,300 a month if she pulls her son Aiden out of his private preschool and sends him to a free TK program in the fall. But she’s still not sure Aiden, who will turn 4 just days before the eligibility cutoff, is ready for the transition.

Recruitment frenzy

The competition over children like Granin’s is particularly fierce in L.A., where the school district has raced ahead of the state by inviting all children turning 4 by Sept. 1 to start in August. The state’s TK expansion timeline does not have the youngest 4-year-olds enrolling until the 2025-26 school year.

L.A. Unified’s marketing spree includes banners hung on every elementary school in the district, billboards across town, dozens of ads on bus shelters, and 100 posters hung inside liquor stores and laundromats declaring, “See You in School! Elementary School Starts at 4 years old.”

LAUSD declined to say how much it has spent so far on TK advertising, saying it is “still finalizing the budget.”

Last year, there were 13,800 TK students enrolled across 317 LAUSD elementary schools. In the coming school year, district officials hope to recruit an additional 10,000 to 11,000 students across all 488 elementary schools — if they can convince families to sign up.

Student enrollment at L.A. Unified has been sagging for the last decade, and the district estimated a further 30% plunge over the next decade. The addition of a new grade for 4-year-olds offers the district an opportunity to make up for some of those losses — a powerful motivator for recruitment.

On a recent Friday, the district held a webinar for “partners” to ask for help.

“At the end of the day, we have 25,000 seats of capacity, and we need to make sure every one of those is filled,” Michael Romero, L.A. Unified’s chief of transitional programs, told participants, which included staff from the L.A. County Board of Supervisors and a variety of community groups including the Parent Organization Network and the Islamic Center of Southern California.

Romero added that the district would be sending along suggested social media posts and emails that participants could send out to their contact lists, along with flyers in English and Spanish. He also offered to staff a booth at fairs and community events where LAUSD employees might have the opportunity to interact with families.

Before the summer, he told participants, every current student at L.A. Unified was sent home with a TK flyer aimed at younger siblings, and a blast of phone calls, emails and text messages went out to parents. “Principals will do a wash, rinse, repeat when they come back in July,” Romero said. The district is also recruiting 200 representatives to knock on doors, reminding families to enroll, he added.

The parent dilemma

Many parents whose coveted 4-year-olds are happily ensconced in their local preschools aren’t sure what to do. Granin posted in a local Facebook moms group for advice from other parents facing the same choice.

“Do I keep him in his daycare/school or send him to TK?” she wrote. “Give me the pros and cons.”

When she found out in April that Aiden could attend TK for free, she was tempted. “Originally I was like, let’s do it. It’s almost the same schedule, and we’d be saving so much money.”

She called her local L.A. Unified elementary school and started the application process. But she had some concerns. She worried he wouldn’t be able to nap in TK, and that switching schools would be a difficult change. She also talked to the director of her son’s current preschool.

“She was like, ‘I need an answer ASAP,’ because she’s recruiting kids to take the spots of the kids who aren’t staying,” said Granin. Meanwhile, the public school was also getting anxious. “I submitted an application but didn’t submit all the paperwork, and they’ve been calling and emailing me constantly.”

Granin said she’s leaning toward keeping her son at his preschool, but she still hasn’t decided.

Fear among day-care providers

The choices that parents like Granin make will reverberate across the preschool and day-care industry.

“We can’t compete with a large organization like LAUSD,” said Victoria Marguleta, who owns and operates A Mother Goose Academy, serving children ages 2-5 in Chatsworth and Valley Village. She knows she should focus on advertising, but “marketing costs thousands of dollars,” she said. “That’s out of reach for us.”

Marguleta started her business 20 years ago after struggling to find high-quality care for her own daughter. “This was my heart’s work. This was my dream job,” she said.

For years, her classrooms were full. But since the TK expansion began last year, she said, all but one of her 4-year-old students who pay privately have left Mother Goose for TK. “We’re losing a whole age group,” she said. The few who remain receive vouchers from the state for their tuition.

As child-care workers struggle to pay bills, in-home providers push for higher wages and urge the state to overhaul rates for its subsidized care program.

At the Chatsworth location, for example, Marguleta once had 54 students; now she’s down to 40. “It makes it difficult to survive if enrollment is so drastically low,” she said.

Marguleta has tried meeting with families to tout the benefits of Mother Goose — quality care, free meals, long hours — but “we can’t compete with free, no matter how high our quality is.” She has tried to recruit more 2- and 3-year-olds to fill the empty slots, but hasn’t had much luck. There’s more demand for infants and toddler care, but she would have to renovate her buildings to create a separate sleep space for them, and she doesn’t have the money.

Most centers actually lose money providing care for infants through 2-year-olds. In addition to the space requirements, these younger students also require more staff members to tend to them under state law, said Dave Esbin, executive director of Californians for Quality Early Learning, a membership association for child-care providers.

“The economics simply don’t work,” said Esbin. “Families can only pay so much. You can’t charge double for infant care...Losing these 4-year-olds is devastating. We’ve seen a lot of our members say we’re closing our doors.”

Even larger day-care programs are struggling to compete with school districts for 4-year-olds.

Young Horizons Child Development Centers has five locations in Long Beach and provides state-subsidized care for children age 6 months to 5 years. Executive director Sarah Soriano said she’s increased her marketing budget to send out flyers, attend enrollment fairs and advertise on Google and Yelp. The push has helped, but she has still lost so many of her older students that she’s had to close four of her 22 classrooms.

“Everywhere you look, the school district is beating me at that game,” she said. “A small nonprofit is no competition for a huge, gargantuan school district.” Soriano said she has a waiting list for infants and toddlers, but they are a losing financial proposition for her.

Wendy Arriaga said her 4-year-old daughter Emily has thrived at Young Horizons, where she’s learned to be more independent and express her feelings. Arriaga, whose daughter was able to attend the center for free last year, worried about how much she might have to pay for the coming year. She also hopes TK might offer a more academic approach.

“I think they’ll focus more on teaching her the difference between numbers and letters,” Arriaga said. “Right now she’s learning things through playing, which I love,” she said, but “she doesn’t know the difference between 2 and E.”

Even other public programs are grappling with losses to school districts, including Head Start, the federal program for low-income child care. Despite the fact that Head Start is free for families and offers extra services like healthcare, nutrition and parent education, the program is still losing older students to TK.

Stacey Scarborough, past president of Head Start California, the industry’s membership organization, said many programs are under-enrolled, putting their grant requirements at risk.

Head Starts have also amped up their marketing. Still, some programs will be switching from preschool programs to “Early Head Starts,” which serve younger children from newborns to age 3.

Christine Altounian, who lives in Mid-City, struggled for months with whether to keep her son Lucas at his beloved co-op preschool or send him to TK. “It was the hardest decision because of the community we built in his preschool. It was the most magical experience ever,” she said.

But the pull of TK was all around her.

“Every time I walk past school, they have banners on the gate saying, ‘Enroll your 4-year-old,’” she said. “People are constantly talking about it in moms groups,” she said. She wasn’t sure about the longer days or the uniforms, but the temptation of a single drop off and pickup for both of her sons was tempting, and it would allow her to invest her time in one school community.

She decided to give TK a try. For now.

“I’m still not even sure I made the right decision,” said Altounian. “I told his teacher if it doesn’t work out, we’ll be back.”

This article is part of The Times’ early childhood education initiative, focusing on the learning and development of California children, from birth to age 5. For more information about the initiative and its philanthropic funders, go to latimes.com/earlyed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.