Space shuttle Endeavour preps for move to vertical landing in new museum

After more than a decade on display at the California Science Center, the space shuttle Endeavour will begin the final trek to its permanent home at a new Los Angeles building in the coming months.

To get ready for the grand move, the state-run museum announced Thursday that crews will begin the installation of the base of the shuttle’s full stack on July 20. Workers will use a 300-ton crane to lower the bottom sections of the twin solid rocket boosters, which are 10,000 pounds apiece and roughly 9 feet tall, to the freshly built lowest section of the partly constructed $400-million Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center.

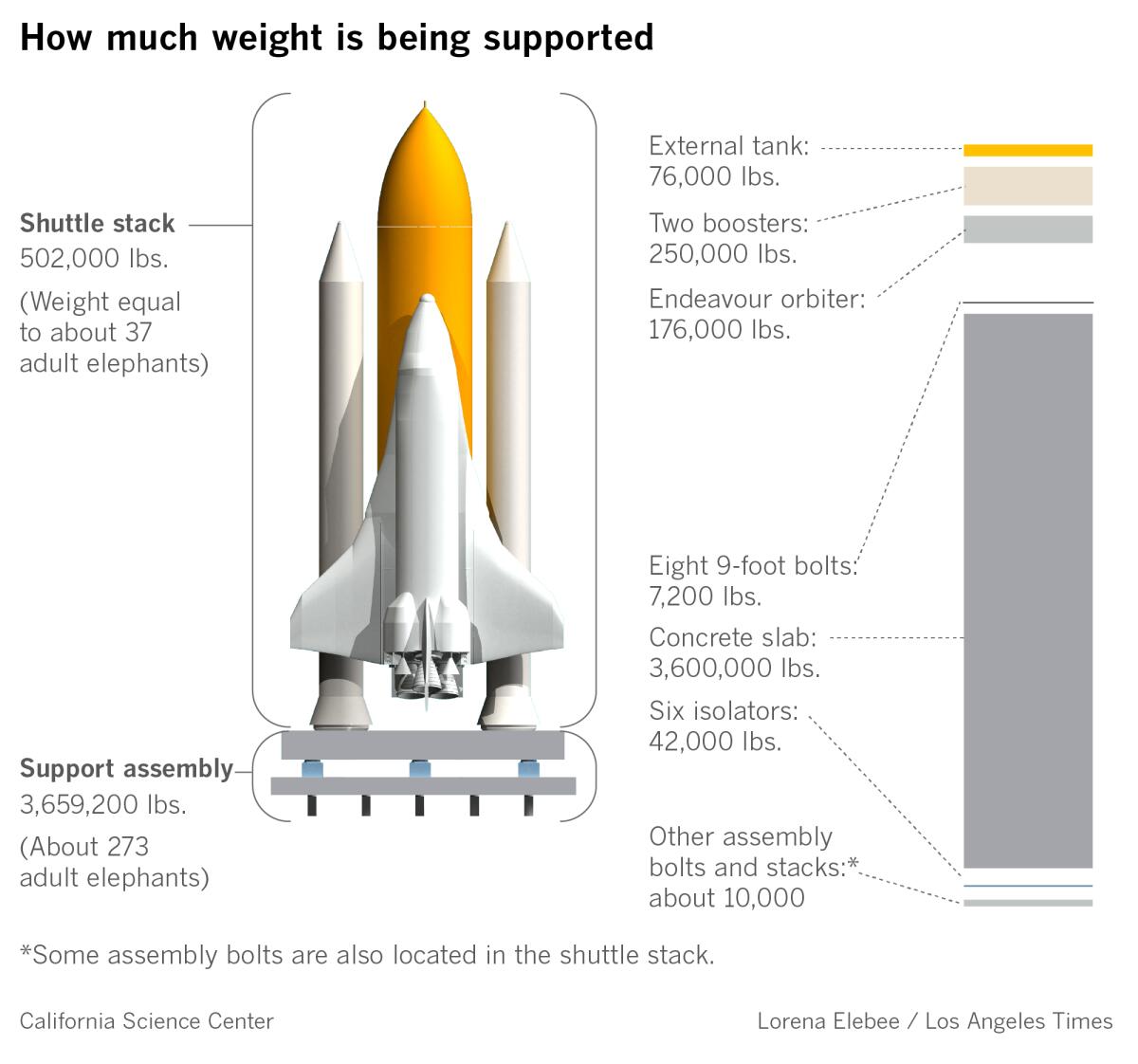

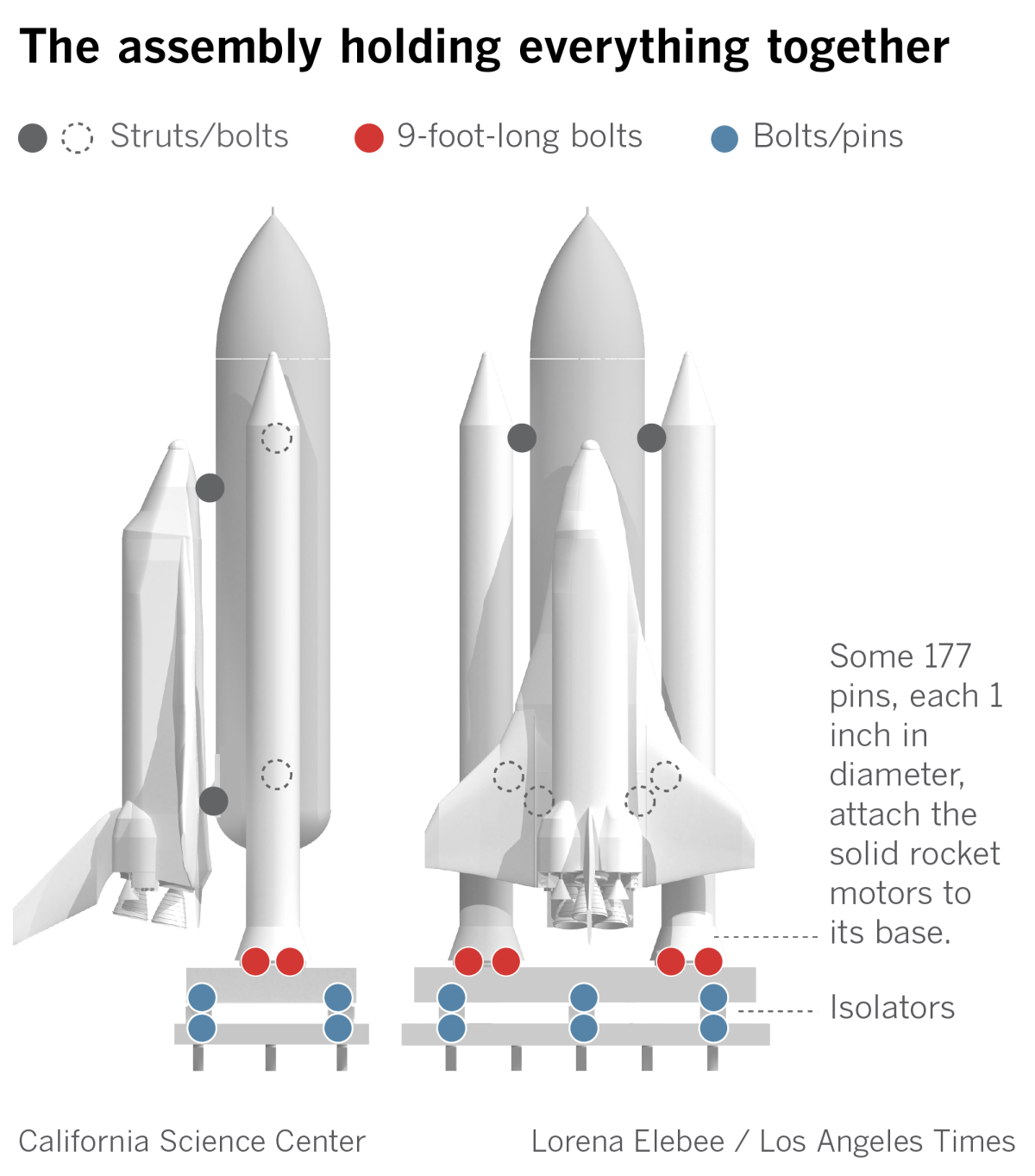

It’ll be the first of many delicate maneuvers conducted over roughly six months (if the weather cooperates). Eventually, all half-million pounds of the full stack — including the shuttle Endeavour and a giant orange external tank — will rest on the base of the solid rocket boosters, bolted to the ground by eight supersized, superalloy fasteners that are 9 feet long and weigh 500 to 600 pounds.

“You could arguably say [the base of the boosters are] the most critical piece to put in because they determine how everything else works,” said Dennis Jenkins, project director for the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center. Even a slight misalignment could cause major problems later on — making it impossible to connect the solid rocket boosters to the external tank, and the external tank to Endeavour.

Thursday’s announcement comes about a year after ground was broken on the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center. It also marks the countdown for Endeavour to conclude its exhibition in a horizontal position, which will end Dec. 31 before the shuttle is carefully moved to the new building site. It could be years before Endeavour will again be available for up-close viewing to museum guests.

In a dramatic finale that could come as early as January, cranes — the tallest of which will be about the height of City Hall — will raise the spacecraft from its horizontal position to point vertically for its final display, where the rest of the museum will then be built around it.

It will be a crowning achievement 11 years after the last space shuttle ever built captivated Californians as it made its final flight aboard a Boeing 747, past the Golden Gate Bridge and Hollywood sign, before landing in L.A. A three-day journey through city streets brought Endeavour to its permanent museum home at the California Science Center.

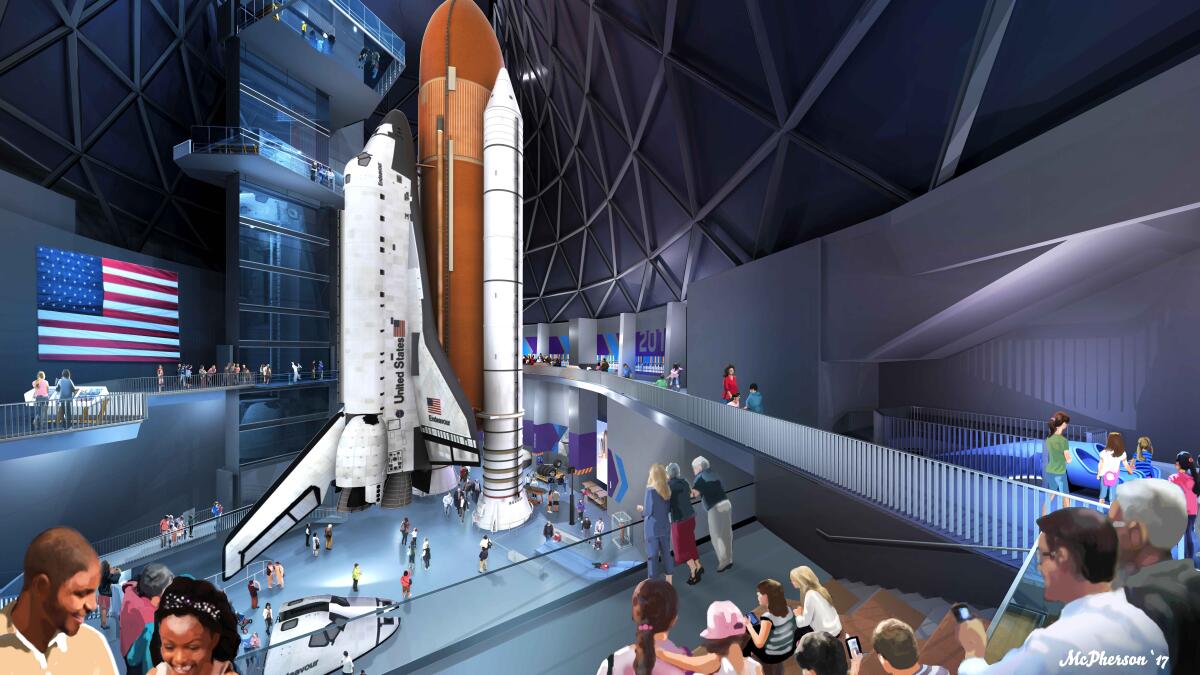

“It’s a dream come true, for sure,” said Lynda Oschin, wife of the late Los Angeles businessman and philanthropist Samuel Oschin, an avid space enthusiast and namesake of the new museum. The exhibit will hold “the only shuttle in the whole world in launch position.”

The exhibit is believed to be the tallest authentic spacecraft displayed vertically in the world. It also has an authentic portable unit called Spacehab, which was used as a lab or storage pod — the only remaining shuttle to have such equipment — in its payload bay. One of the payload bay doors will be open and viewable to the public.

Endeavour, the so-called jewel of the shuttle fleet that flew 25 missions in space, will be viewable from multiple platforms — including beneath the orbiter’s three main engines as well as looking down, through a glass floor, directly at its nose.

Of the three shuttles left, Endeavour will be the only one displayed upright

“It’s all real hardware. And we’ll be the only place in the world with a stack of all real hardware,” Jenkins said.

The full-stack configuration of Endeavour is so tall that the museum will rise 20 stories to make room for it. And to keep the views unobstructed, the building has been engineered with no vertical supports except its walls.

The building will feature a “diagrid” — a diagonal grid — developed by engineering firm Arup and covered by a stainless steel facade. Diagrids have been used in other tall buildings, including the 46-story Hearst Tower in New York City, the iconic 40-story ovular Gherkin skyscraper in London and a section of the egg-shaped London City Hall.

The most dramatic part of installation will come as early as January when the 66,000-pound, 154-foot long external tank — the last of its kind in existence — will be rolled out and hoisted by cranes into a vertical position.

The same month, Endeavour will be moved from its temporary hangar, on the western edge of the California Science Center. It’ll first be rolled onto the lawn just north of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and south of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

It’ll be parked there for a couple of days as crews prepare equipment to move it to the eastern edge of the science center. Workers will use self-propelled modular transporters, similar to those used in 2012 when Endeavour was moved from Los Angeles International Airport to the museum.

In a procession that will take as much as a day, Endeavour will be moved east on State Drive, past the Exposition Park Rose Garden, and be parked next to its new museum home, just west of the California African American Museum. The move will be tricky: At one point, Endeavour will need to be jacked up 4 or 5 feet — to avoid striking a building — moved and then jacked back down for the rest of the journey.

Finally, Endeavour will be parked at the new building, which by then will consist only of a concrete wall about four stories above ground. The bulk of the structure — the steel diagrid — will be built later.

As if they were performing delicate surgery, a crew inside the California Science Center museum hoisted a 3,000-pound portable space lab and storage pod inside the space shuttle Endeavour’s huge cargo bay Thursday, reuniting the retired orbiter with a piece of equipment it used on some missions over its two decades of flight.

Once at the building site, Endeavour will be attached to a sling — a large metal frame that will support it as it’s hoisted from a horizontal to a vertical position. From there, two cranes will be on hand: an 11-story, 400-ton hydraulic crane next to Endeavour’s tail and a 40-story crawler crane, probably weighing 900 to 1,000 tons, next to the orbiter’s nose.

The shorter crane will lift the tail of the spacecraft while the taller crane lifts its nose. Once Endeavour is aimed toward the stars, the shorter crane will be disconnected.

The larger crane then will lift Endeavour — raising its nose as high as 300 feet from the ground — and gently swing the spacecraft in a delicate maneuver to position it into its final display. All of this will take place while the crane operator works without being able to see what is happening — the line of sight will be obstructed by the base of the building.

“It’s going to be quite a show,” Jenkins said.

And it’ll be quite a challenge too. When this work was done before shuttle flights at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, it was conducted inside the Vehicle Assembly Building — one of the largest buildings by volume in the world, rising more than 50 stories. It had been built to assemble Saturn V rockets that launched astronauts to the moon on the Apollo missions and later used for the space shuttle program.

In Los Angeles, the installation will occur outdoors, so winds will be a concern. The lifting and lowering will have to be planned around the weather, and probably during a very long night when winds tend to be minimal, Jenkins said. Bolting Endeavour to the external tank will probably take another full day.

But before any of this can happen, the museum needs to ready the area in which Endeavour will be positioned. That process begins in earnest July 20 — Space Exploration Day, in honor of the anniversary of when U.S. astronauts first landed on the moon.

It’ll take roughly two hours that day to hoist the bases of the solid rocket boosters — called the aft skirts — and place them in the lowest section of the new building. The boosters, the white rockets seen below each wing of Endeavour at liftoff, produced more than 80% of the lift during takeoff.

The boosters are massive — about the size of the fuselage of a Boeing 757, which can carry roughly 200 people.

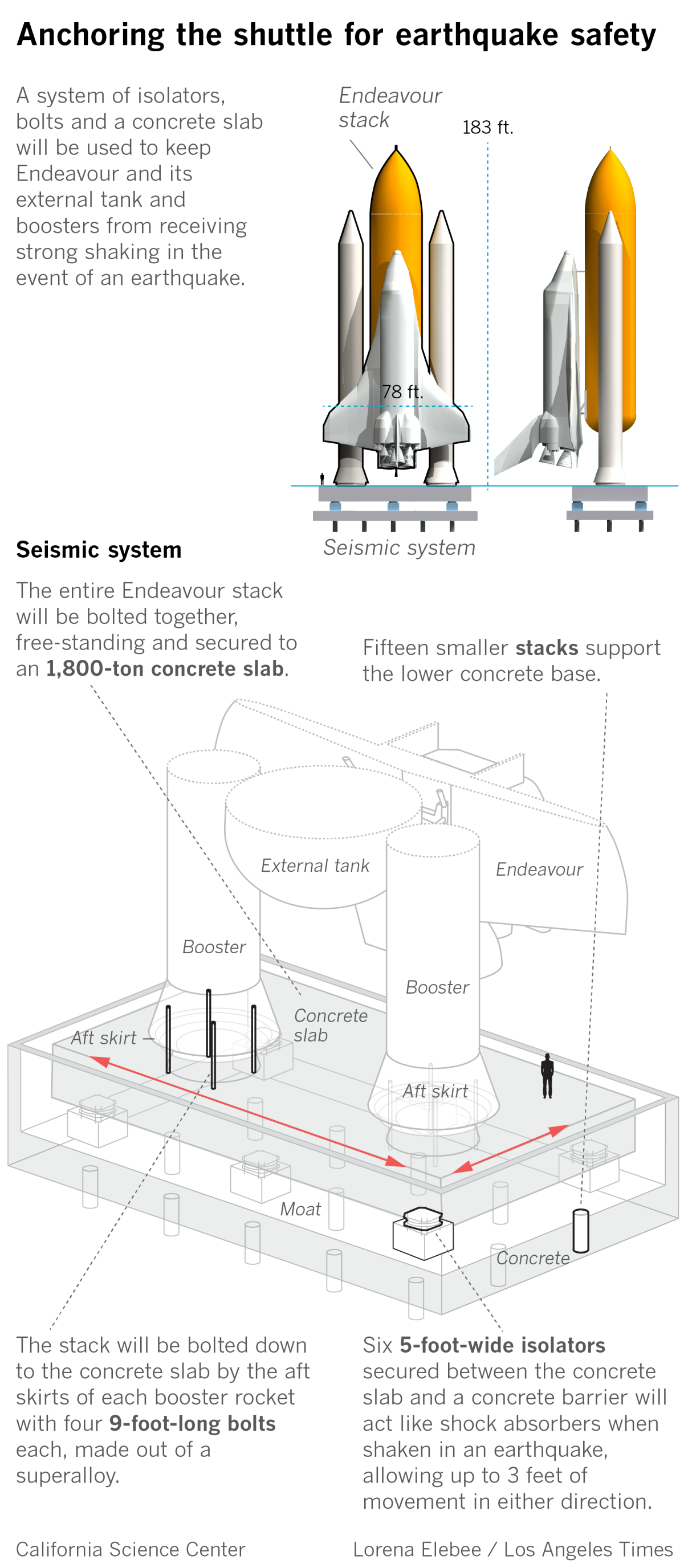

It could take weeks or months for workers to verify they’re in the precise location before they’re bolted into an 1,800-ton concrete slab that’s 8 feet thick.

To protect against damage from a major earthquake, the slab is held up by six seismic isolators, each about 5 feet in diameter, with a ball bearing inside. They’ll act like shock absorbers on a car and will keep Endeavour from badly rocking during a quake. The seismic isolators will allow the shuttle to move up to 3 feet side to side without crashing into the building foundation.

“So it should be well-protected from earthquakes,” Jenkins said.

Endeavour: Final Journey The space shuttle Endeavour makes its final journey to the California Science Center in Los Angeles, marking the end of NASA’s shuttle program.

The bolts are made of a superalloy called Inconel, made roughly once a year in only a handful of mills in the U.S. Jennings bought nine of them — with one as a spare.

The 9-foot bolts are much longer than their original counterparts at the launchpad, which were only about 2½ feet long and attached to explosive nuts that ignited during liftoff (the museum display will not have explosives). The longer bolts were needed go through the 8-foot concrete slab beneath the base.

The bolts are technically studs — basically rods that are threaded on both ends. They’ll be lowered into position through 6-inch diameter holes in the concrete slab. To be fixed in place, a nut on the top will have to be tightened using an incredible half-million pounds of torque — roughly 5,000 times the force needed to loosen the bolts when replacing a tire on a car.

There’s no practical way a wrench can be used to produce that torque. So the Science Center instead bought custom-made hydraulically powered “stud tensioners” capable of producing that much torque. Four of them will be put on all four bolts on one aft skirt at a time and turned on simultaneously so “they all go down exactly together,” Jenkins said.

Getting all the details right will be critical. Should the bottom of the boosters be out of alignment by even one-eighth of an inch, that could mean that “we won’t be able to attach all the parts,” he said.

Crews will use laser surveying equipment to make “sure that everything’s perfect,” Jenkins said.

“That explains why we’re starting with the aft skirts much earlier than the rest of the stuff going in because we’ve got to get them right,” said Jeffrey Rudolph, president of the California Science Center. “If there’s any discrepancy and they’re not exactly aligned, then the attached hardware won’t fit further up.”

Once the base of the boosters is in place, installation of the 115.6-foot middle section containing the solid rocket motors will begin. Cranes will again be used to lower the motors, where 177 pins, each 1 inch in diameter, will be used to attach them to their base.

The motors will be moved sometime in October, mostly via freeways, from Mojave Air and Space Port about 70 miles north of L.A. to the Science Center. It will be another opportunity for spectators to watch parts of the spacecraft lumber through Southern California.

The installation of the upper section — the 27-foot “forward assembly” — will come next.

That will set the stage for installation of the external tank, followed by Endeavour. It will be connected to the external tank in three locations; each solid rocket booster will be affixed to the external tank in four spots.

Once the full stack of the space shuttle is completed, the rest of the building will be constructed, followed by the time it will take to install exhibits. It could be two or three years before the new museum is open to the public.

Oschin said she expects the new exhibit will be inspirational.

“It’s gonna make kids want to do this,” Oschin said, recalling a girl at the Endeavour exhibit asking if she could be an astronaut. “I said, ‘Of course you can be an astronaut. You just never give up on anything.’ ”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.