MADERA, Calif. — It was dinnertime when Sabrina Baker, a mother of six, felt the familiar twinge of contractions.

At first, she brushed it off as Braxton Hicks, false labor pains not uncommon in the late stages of pregnancy. But after dinner that night in early January, the pain sharpened and radiated to her back. The contractions intensified, and Baker knew this baby girl was coming fast.

She had a decision to make — and the options weren’t good.

Two days earlier, Madera County’s only general hospital had shut its doors. The abrupt closure of Madera Community Hospital and its affiliated medical clinics capped years of financial turmoil. Still, most residents in this rural county in California’s geographic center were caught off guard, unaware of just how much was at stake until their hospital was gone.

Baker knew she couldn’t make it to the next closest hospital, in Fresno, a roughly 45-minute drive.

Twenty-five minutes after the first contraction and two pushes later, she delivered her daughter, alone, on her tan love seat. The baby was breech, which upped the anguish and the risk during delivery. When it was over, Baker tied the umbilical cord with new shoelaces and wrapped Onax in a San Francisco 49ers blanket. An ambulance rolled up 20 minutes later to take mom and baby to the hospital.

“I mean, I’m lucky,” Baker said, standing outside her home in a swath of Madera County surrounded by cropland and almond groves. “We could have died.”

During its half-century run, Madera Community Hospital provided a crucial link to healthcare for the 160,000 people who call Madera County home. Spanning from the heavily farmed floor of the eastern San Joaquin Valley to the forested central Sierra, Madera is majority Latino, and 20% of the population live in poverty.

For most residents, the hospital was more than a place to go when disaster struck. Madera Community helped them sign up for Medi-Cal, the state’s version of Medicaid insurance for low-income adults and children. It was readily accessible by bus, and it coordinated services with community clinics where residents could receive routine care and prescriptions. Sometimes the hospital was the only place people saw a doctor. Unlike the many private providers that exclude certain types of health insurance — including Medi-Cal, with its notoriously low reimbursement rates — Madera Community served everyone.

“It’s the worst thing that could have happened to us,” Tony Camarena said of the closure. Camarena runs a business that enables sending money abroad, and many of his customers made use of the hospital’s services, he said.

Healthcare experts say Madera’s closure — and the untenable financial realities that brought on the collapse — offer a case study on the challenges facing rural hospitals across the country. Nearly 30% of all rural hospitals in the U.S. — more than 600 of them — are at risk of closing, according to the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform.

In California, nine rural hospitals have been shuttered since 2005, and 17 are at risk of closing. Kaweah Health Medical Center in Visalia, about an hour’s drive from Madera and the largest hospital in rural Tulare County, is among those bowing under serious financial problems.

Experts in healthcare economics say rural counties generally have fewer patients than suburban and urban communities — and a high share of those patients are low-income and enrolled in Medi-Cal. That means there are fewer patients with private insurance whose payments can offset Medi-Cal’s low reimbursement rates. Small hospitals also have less muscle than bigger ones to negotiate rates from private insurance companies.

COVID-19, which pummeled the San Joaquin Valley, exacerbated the financial decline. Farmworkers whose jobs were deemed essential worked at great risk of exposure. Hospitals across the valley were overwhelmed with surge after surge, and farming counties like Fresno and Madera saw some of the state’s highest infection and death rates.

“Fifty-two percent of California’s hospitals are operating in the red — they are losing money every day. That is unprecedented,” said Carmela Coyle, president and chief executive officer of the California Hospital Assn. “And while there were hospitals losing money before the pandemic, the pandemic just sucked so many more hospitals into that financial hole that we are really now looking at crisis circumstances in many parts of the state.”

For Madera Community Hospital, already operating on thin margins, rising costs for medical equipment and the spike in salaries for traveling nurses who were in high demand during the pandemic proved too much to absorb.

Hospital leaders tried to broker a deal with Trinity Health, a nonprofit Catholic healthcare system that owns Saint Agnes Medical Center in Fresno. Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta conditionally approved the sale of the hospital but placed terms on the deal that would have required Trinity to set price caps on certain services, maintain charity care programs and commit to providing emergency care and clinic services for five years. Trinity Health pulled out of the deal in December.

Madera Community Hospital shut its doors and by March had filed for bankruptcy.

Residents were anxious. Many don’t have cars and worried about how they would get to hospitals in other counties. Longer wait times at those remote emergency departments meant they would miss the work and pay they need to survive.

Time hasn’t healed those concerns. It has created new ones.

“It really put a community against the wall,” said Linette Lomeli, executive director of the Madera Coalition for Community Justice, a grassroots organization that helps residents access food, housing, employment and, now, medical care.

Along Highway 99, a main artery that bisects miles of farmland, Madera Community Hospital stands frozen in time. Three blue tarps hang over the entrance to what was once the emergency department. The grass outside is ankle high, and leaves are piled against the curb.

Inside, a haunting silence hung in the darkened hallways as hospital CEO Karen Paolinelli surveyed the place where she started her career four decades ago. She sighed as she pointed out the CT scanner the hospital had just purchased to replace a 15-year-old machine that was always breaking. The new one wasn’t even plugged in when the hospital closed.

Paolinelli walked past rows of empty beds in the intensive care unit, a place that was packed with patients during the pandemic, and thought about the doctors and nurses who stepped up during the terrifying heights. The hospital and its clinics were a lifeline for the community, she said.

In the weeks leading up to the closure, it was as if opportunities to save the hospital kept slipping from her grasp, she said. But she holds out hope that a potential partner might see value in helping Madera Community reopen.

“If we don’t do it quickly, it may never open again,” she said.

The fallout from the closure resonates beyond Madera County. On a recent weekday evening, the emergency department at Community Regional Medical Center in Fresno, 35 miles south, overflowed with patients. A security guard told those arriving they’d have to wait outside. There was simply no room.

The ER also spilled over at Fresno’s Saint Agnes Medical Center, and rows of people sat outside under a white tent, hoping to be called.

“It’s always been busy, but it’s just snowballed,” said Xiomara Russell, a licensed vocational nurse at Community Regional Medical Center who formerly worked at Madera Community. “We have ambulance waits and a full lobby all the time.”

Russell said access to medical care was tenuous in Madera, and people used the emergency room as a way to get basic medical needs met. She worries people will delay getting care until their conditions are harder to treat. Like Paolinelli, she wants to see Madera Community reopen.

“It has to,” she said. “There’s so many people who need it.”

State legislation could provide the first step.

California lawmakers have agreed to lend $150 million to financially distressed hospitals.

Last month, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation creating the Distressed Hospital Loan Program, which will provide $150 million in zero-interest loans to hospitals teetering on financial ruin. The aim, according to legislators, is to help struggling hospitals stay open and to assist with the reopening of recently closed ones like Madera Community.

“There is no other option but to continue to push and fight and demand that these resources come to our community so that we do have a hospital that opens,” said Assemblymember Esmeralda Soria (D-Fresno), who co-authored the measure.

Still, it’s not clear whether Madera’s hospital will be able to access the funds, or whether they would be enough to reopen the doors anytime soon. Deidre da Silva, chair of the hospital’s board of trustees, argued in a May 23 letter to lawmakers that the loan program won’t “lead to fiscally viable operations” at rural hospitals unless the state also finds a way to raise Medi-Cal rates.

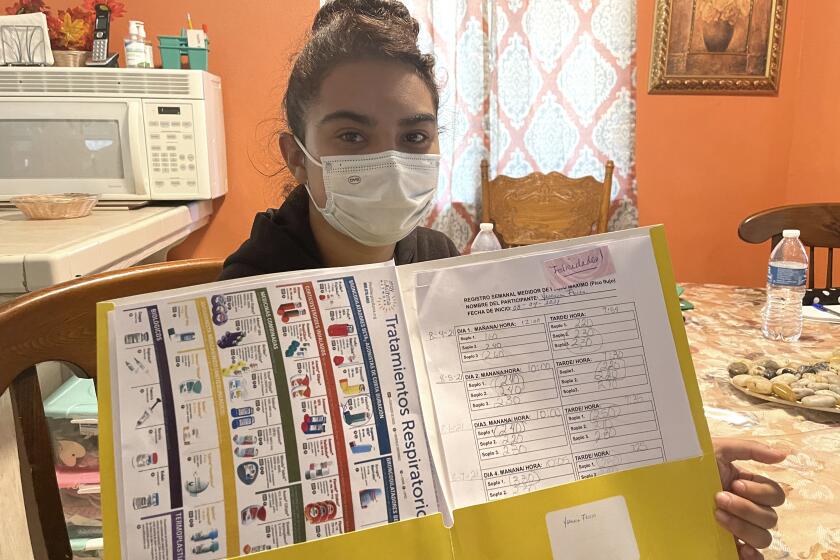

Meanwhile, residents like Cristina Guzman are struggling to find a replacement for the ongoing care and prescriptions they received through Madera Community. Guzman, who is Mixtec, was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2018, a few years after she quit working in the fields in Madera because of her failing health. In recent years, she has turned to the hospital for help managing her asthma and an array of other debilitating conditions.

The hospital’s reopening would be “glory to God,” she said in Spanish. She stood in her yard, her hands outstretched and her eyes looking toward the sky as she pondered the idea. “That would be very good for me.”

In January, California’s Medicaid program will begin helping low-income asthma patients with services such as replacing mattresses and installing air purifiers. The rollout promises to be chaotic.

After Madera Community Hospital closed, the Binational Center for the Development of Oaxacan Indigenous Communities and the Jakara Movement, which provides outreach to Madera’s Sikh community, conducted a survey of more than 300 residents to understand how these groups have been affected.

More than half of those surveyed said outlying hospitals pose a travel challenge, and many said they lacked transportation. Some Indigenous farmworkers had no idea the hospital had closed.

Kashwinder Basra, 29, who grew up in Madera, said the lack of a hospital has pushed her family to consider uprooting. Her aging mother has been diagnosed with arthritis and osteoporosis and needs more medical care than the area can provide.

“We’re planning to leave to go to Clovis, because it’s closer to the hospital,” she said. “With everything happening, there’s no point in living here anymore.”

Others fear that their lives are in danger without a hospital nearby.

Maria Rios has had Type 2 diabetes since she was 30, and at 59, she is dealing with the agonies of renal failure.

Rios used to work the fields of California and Florida, picking cucumbers, chiles, onions and tomatoes. But in recent years, her weeks have fallen into a familiar pattern: Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, she takes a van, paid for by Medi-Cal, to a dialysis center. For three hours, she receives treatment. She is restricted to one bottle of water each day.

When the symptoms of dehydration set in, as they frequently do, she would seek care at Madera Community Hospital, an eight-minute drive from her home. They would give her IV fluids and pain medicine, she said.

Since the hospital’s closure, Rios has turned to Fresno’s Saint Agnes Medical Center. Twice now, her sons have taken off work to drive her to the hospital in search of something to ease her pain. Both times, she said, the waiting rooms were packed with people in distress. She waited hours to be seen, only to be told that the hospital was not authorized to prescribe her medications.

She went home and made herself mint tea instead.

Rios said her friend Juana, who was also on dialysis, used to ride in the van with her to the center. But in May, she learned that Juana had died in an ambulance on the way to Fresno. She left behind two teenage daughters, who are living with their grandmother, Rios said.

“She didn’t make it to the hospital,” Rios said in Spanish, staring down at the tattered Christmas tablecloth on her kitchen table. “And they came back because she died on the way.”

Rios, who is Zapotec, worries that she may be next. She has been on a waiting list for a kidney transplant for years, but she has not heard when an organ might be coming.

“I told my sons, ‘Prepare yourselves, because at any time, I could die from the pain,’” she said. “Without a hospital [in Madera], I won’t come back.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.