Killed in Germany in 1944, Army Tech Sgt. Matthew McKeon was unaccounted for until recent DNA tests led to a San Diego homecoming, just in time for Memorial Day

Killed almost 79 years ago in Germany during World War II, his body left behind in the fury of combat, U.S. Army soldier Matthew Louis McKeon never had a grave that his family could visit.

Now there is one, at Miramar National Cemetery, just in time for Memorial Day.

The recovery and identification of his remains are part of a project to repatriate U.S. service members from one of the war’s bloodiest and least-remembered battles, Huertgen Forest. U.S. forces there expected to rout the Germans quickly in the fall of 1944 and instead found themselves in a six-month quagmire that claimed 34,000 casualties.

Although efforts to find the soldiers’ remains started soon after the war ended, they were stymied by the thick forest and rugged terrain, and by the limited forensic tools of the day.

Advances in technology, especially DNA, have closed the gap and are making possible funerals for the fallen, like the one for McKeon that took place at Miramar last week.

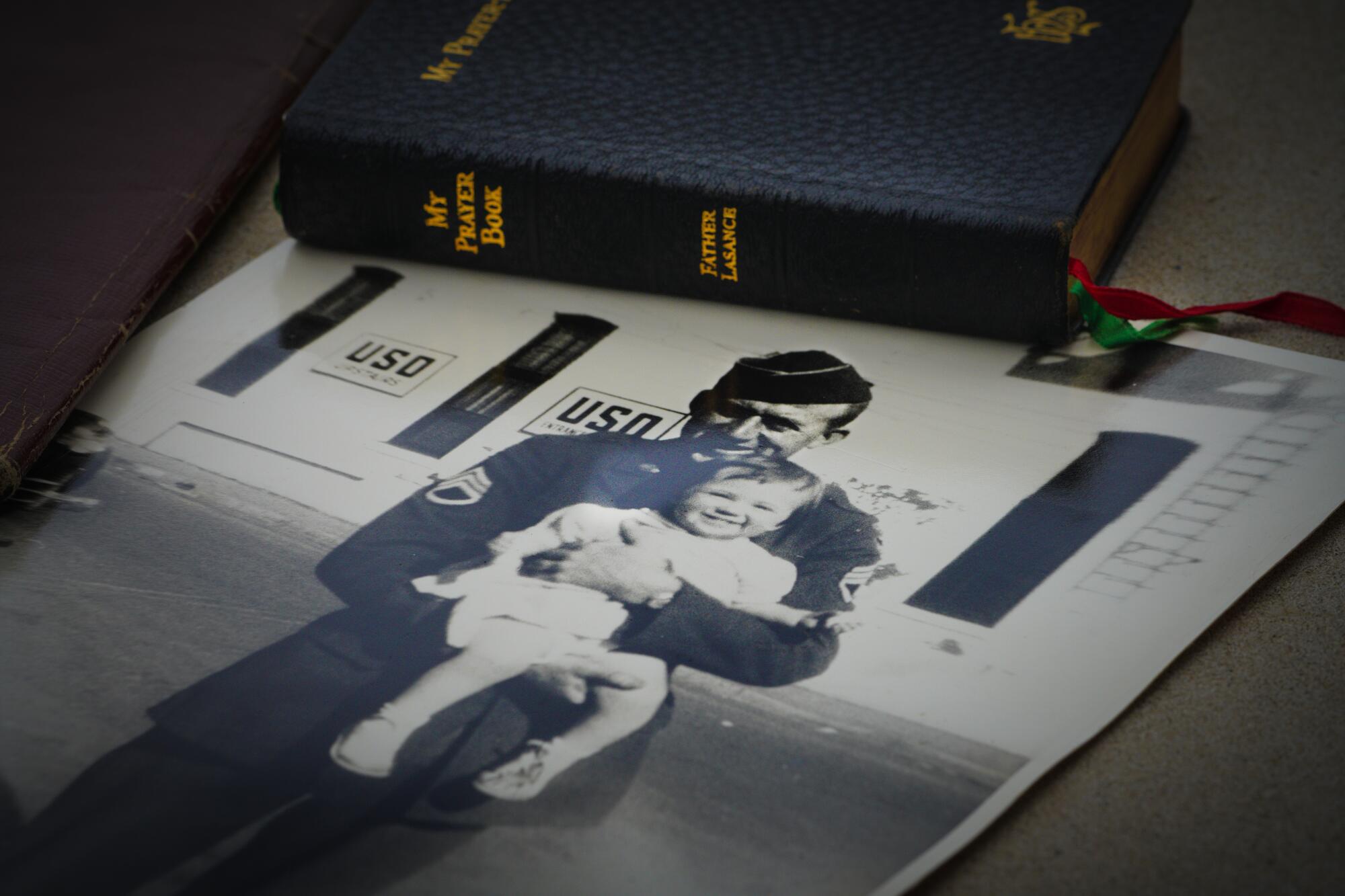

About two dozen people attended. His daughter, Marcia, who was 2 when he died, came from her home in Escondido. One of his nephews flew in from Georgia, another from Florida. Grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and a 7-month-old great-great-granddaughter were there, most of them from the San Diego area.

The baby girl cried when the first shots from seven rifles went off during the service’s traditional three-volley salute. But there were far more smiles than tears on the faces of those who were there.

That’s a testament to the grief-easing power of the passage of time, but it’s also a reflection of the joy that comes from finally having an answer to a question that’s haunted the family for decades. This was a homecoming they never expected.

More than 400,000 U.S. service members died in World War II, and there are still some 72,000 unaccounted for, according to Defense Department records.

In many of their families, silence descended as the years passed. It wasn’t comfortable to talk about who was missing, and why. But the absence had a presence.

That’s why one of the nephews who attended the Miramar funeral had a familiar name: Matthew McKeon. He’s named after the slain soldier, a man he never met.

He carried with him in a jacket pocket a photo of his uncle wearing an Army uniform. He pulled it out and showed it to people he met.

“It’s just amazing,” he said, “that this is happening.”

‘With regret’

McKeon was born Dec. 22, 1918, on his family’s farm near Frankfort, Kan., and was a football star in high school. He enlisted in the Army 18 months to the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor that ushered the U.S. into World War II. He was 24 and married with a young daughter.

Assigned to the 4th Division’s 12th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Battalion, Company K, the tech sergeant was sent to Europe to fight the Germans. On Nov. 9, 1944, he was fighting them on German soil.

The battlefield was Huertgen Forest. Allied forces had the Germans in retreat, chased out of Paris and into a 50-square-mile area that straddled the German-Belgium border. The battle had begun in September, and some U.S. generals expected it to be over by Christmas.

They miscalculated. The muddy terrain made it hard to advance through the woods, and the Germans were dug in with concrete forts, barbed wire and land mines.

McKeon’s Company K was ordered to the front lines near the town of Germeter. They were on the right flank of an attack that was supposed to clear the woods of German forces who had been shooting at vehicles on a nearby road.

They were met with heavy artillery and mortar fire and bogged down after several hours of fighting. McKeon’s platoon breached the German fortifications but got cut off from the rest of the company. It was wet and cold. As night fell, soldiers settled into foxholes.

By the next morning, they’d been forced to retreat.

“Due to the intense combat and thick forest,” an Army report concluded, “the remains of many fallen Americans, including those of T Sgt McKeon, were not recovered by the withdrawing troops.”

Now living in Euclid, Ohio, his family received word that he’d been killed in action. They’d been planning a birthday celebration for his daughter, Marcia, who turned 2 that month. Now they had to think about a different kind of ceremony.

They received conflicting reports about the whereabouts of his remains. A chaplain wrote to his mother and said there was a grave in a cemetery in Belgium. But when his wife, Jean, asked the Army’s Grave Registration Service for a location and a photo, she was told no information was available.

On Nov. 5, 1946, almost two years after McKeon was killed, his mother sent a letter to the War Department in Washington. The clean precision of the typewritten words couldn’t disguise their anguish.

“Dear Sir,” the letter began, “Could you tell me where my son is buried?”

They couldn’t. Seven months later, his widow, who had remarried and was living in Phoenix, made a similar query.

“We have never been notified where he was buried,” her handwritten letter said. “My daughter, Marcia Jean McKeon, & I would certainly appreciate your reply.”

The reply, a month later, expressed “deep regret,” but it had nothing new to report.

By late 1951, the military was wrapping up its efforts to repatriate the dead from World War II. Another armed conflict was underway, in Korea, and fallen soldiers there became the priority.

In a letter to McKeon’s widow, a colonel apologized for the earlier misinformation provided by the chaplain. No grave had been found in Belgium, he said, or anywhere else.

“The Department of the Army has concluded that his remains are not recoverable,” the colonel wrote. “Realizing the extent of your loss, it is regretted that there is no grave at which to pay homage.”

Case X-4458

In October 1946, German crews were sweeping the Huertgen Forest for land mines. They came across human remains in what might have been a foxhole.

The body had no dog tags or other identification, but the clothes — remnants of a herringbone twill jacket, an olive-colored shirt, wool trousers — suggested he was American.

Investigators with the U.S. Grave Registration Service took the remains to Neuville, Belgium, for processing and gave them a number, X-4458. Because of their condition, not much was learned. There was no skull, precluding any efforts at an identification through dental records.

Anthropologists looked for other evidence — previously broken bones that could be matched to X-rays in medical records, for example — that would enable them to match the remains to a soldier they knew to be missing. They were unsuccessful.

In June 1949, the bones of X-4458 were buried in Plot A, Row 31, Grave 3 at the U.S. military cemetery in Neuville, now called Ardennes American Cemetery.

And there they sat.

In 2016, the newly formed Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency began a project to solve the mysteries that time and circumstance had left in Huertgen Forest.

Officials had a list of about 200 unidentified Americans who had died in or near the woods. Historians combed through battle reports and unit rosters, compiling maps of the areas where individual soldiers were believed to have fallen.

They compared those with records showing where remains had been recovered over the years and began creating lists of possible matches.

Genealogists constructed family trees and reached out to possible relatives, asking them to swab their cheeks for potential DNA matches with material extracted from the bones of the dead soldiers.

In 2021, the remains known as X-4458 were exhumed and sent to the Accounting Agency lab at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. Anthropologists inventoried the skeleton and estimated that the soldier was between 64.2 inches and 69.8 inches tall. They calculated his age as older than 18.

McKeon was 25 when he died. His height was 67 inches.

DNA was extracted from the right humerus and the left femur of the remains. It was compared with DNA from several of the missing soldiers’ relatives, including McKeon’s daughter, his namesake nephew and a niece.

The results from a medical examiner’s report, written in January, were unequivocal: “The laboratory analysis and the totality of the circumstantial evidence available establish the remains are those of Technical Sergeant Matthew Louis McKeon.”

His remains are among 50 the Accounting Agency has now identified from Huertgen Forest.

Together again

McKeon’s 99-year-old widow, Jean, died two years ago, before the identification was made. But she knew they were looking. She’d provided a DNA cheek swab too, just in case it was helpful.

Although she’d remarried, she always considered McKeon “the love of her life,” according to Krista Neville, her granddaughter-in-law. And after she died, family members kept some of her ashes.

At last week’s Miramar funeral, Jean’s urn was up front, on a table, as an honor guard brought forward a box with the newly cremated ashes of the man with whom she’d once expected to raise a family and grow old. Now they would be together again.

Psalms were read, the Lord’s Prayer recited. Rifles were fired. A bugler played taps.

And an Army officer in a dress uniform knelt on his right knee and presented a folded U.S. flag to McKeon’s daughter, Marcia, “on behalf of a grateful nation.”

The marble headstone for the grave was resting against a table during the service. It has McKeon’s name on it, and below that Jean’s, and then on the bottom line a single word.

Loved.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.