After 40 years, Boyle Heights priest still irks politicians and fights for his flock

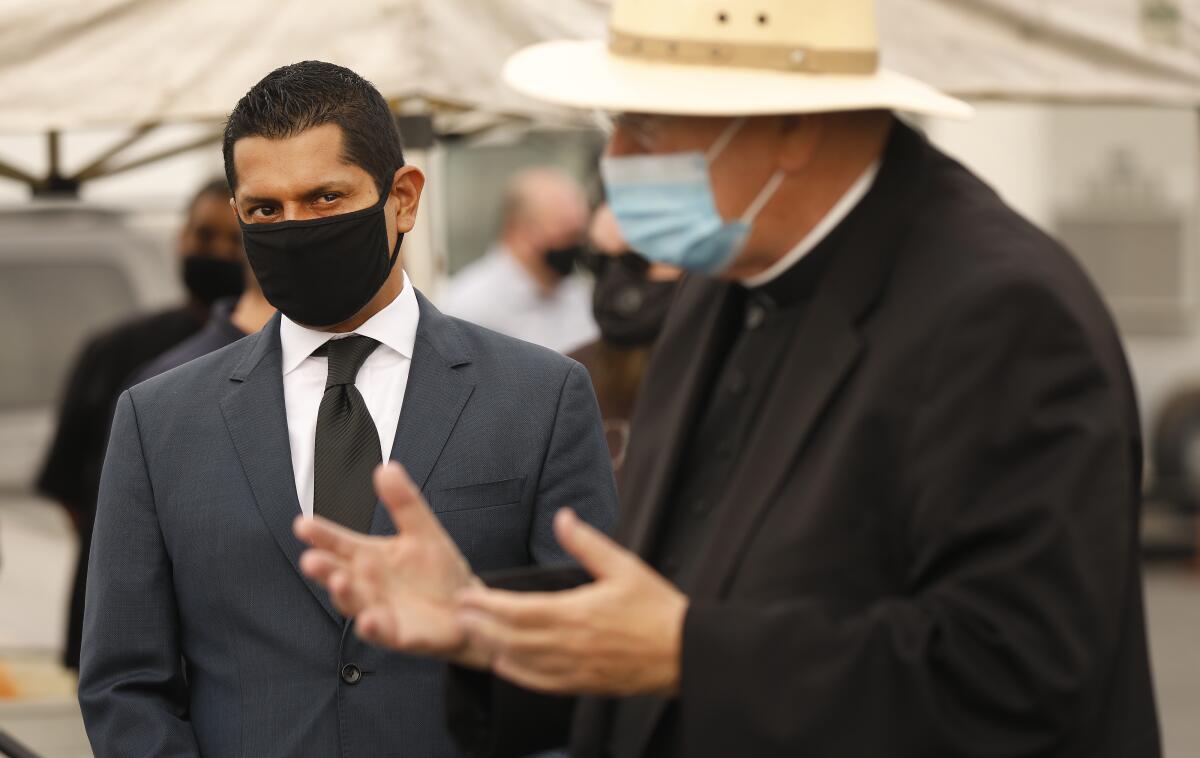

Msgr. John Moretta began the meeting with a prayer of thanks that the community would be able to “express its opinions.”

He then segued into a message that was not so kumbaya, warning that Boyle Heights was famous for its social justice movements and would not stand for any cochinadas, or garbage.

At Resurrection Catholic Church that evening last June, the temperature of the overflow crowd quickly rose, with many speakers bashing a plan from the owner of the old Sears building to house thousands of homeless people.

Chants of Fuera! — “Get out!” — rang through the auditorium.

After three hours of relentless anger from the crowd, project manager Bill Taormina declared the plan “dead” and agreed to consider community input in future proposals.

But fallout from the rancorous meeting soon followed, with much of it landing squarely on Moretta, the host.

The archdiocese received a complaint alleging that the priest had fomented “a lynch mob mentality.”

Los Angeles City Councilmember Kevin de León, who was singled out by many speakers even though he was not at the meeting, called the hostility “disgraceful.” A De León staffer who fielded much of the ire said he was “disappointed” at not receiving a personal apology from Moretta.

Moretta eventually did apologize, saying he had allowed the meeting “to get out of hand.”

A plan to house up to 10,000 homeless people on the former Sears campus in Boyle Heights draws backlash from residents.

In four decades as Resurrection’s pastor, Moretta has been a respected leader on high-stakes community issues, which has sometimes made him a lightning rod for criticism, including from elected officials.

From a proposed prison near Boyle Heights to lead contamination from an Exide battery plant, the Italian American native of South L.A., who jumpstarted his fluent Spanish in a Mexican town in the 1960s, has fought against threats to his mostly Latino, low-income parishioners, all while marking the milestones of their lives at baptisms, quinceañeras, weddings and funerals.

“I know some priests want to be neutral, but I can’t,” said Moretta, 81, whose old-fashioned diction evokes Warner Bros. films of the 1940s. “If people need help, I’m going to help. That’s the way I’ve always seen it.”

Six feet one and heavyset, with a slight stoop and closely cropped white hair, Moretta favors black button-down shirts or white guayaberas when not in his priestly cassock.

He grew up attending Catholic schools, graduating from St. Pius X High School in Downey. There wasn’t a single moment in which he suddenly found his calling, like in the movies, he said. Rather, his decision to become a priest “was gradual and fostered by the love shown to him by the priests and nuns” at school.

After seminary school in Camarillo, he worked as a young priest in Southern California, including at St. Boniface in Anaheim, St. Augustine in Culver City and St. Hilary in Pico Rivera, before landing in Boyle Heights in 1983.

As Moretta settled into his new parish, community activists were ramping up their efforts against a proposed 1,450-inmate prison across the L.A. River from the neighborhood.

In the summer of 1986, Moretta and landscape architect Frank Villalobos invited dozens of Neighborhood Watch leaders — mostly women — to Resurrection to organize an anti-prison march, along with a group of 47 civic organizations called the Coalition Against the Prison in East Los Angeles.

Moretta christened the female leaders the Mothers of East Los Angeles, or MELA, and became their media spokesperson, joining them on weekly protest marches.

With Villalobos and business owner Steve Kasten, Moretta donated tens of thousands of dollars for the women to travel to Sacramento and lobby lawmakers.

A great pride flowed through the East Los Angeles community with the movie “Stand and Deliver,” Edward James Olmos’ great depiction of Jaime Escalante’s work with the math students at Garfield High School.

“He very much loved his people and would do anything,” said Teresa Marquez, now 75, president of the Mothers of East Los Angeles and a founding member. “He stood up for us when so many others didn’t.”

As a leader of the movement, Moretta found himself at odds with a powerful politician.

Soon after being elected to represent the area, Assemblymember Richard Polanco had cast a key committee vote that revived the prison project, prompting some to label him a “sellout.”

Moretta and the activists stalled the project for years with lawsuits and calls for environmental impact reports. They eventually won converts in the state Legislature, including Polanco. Some couldn’t forgive Polanco, but Moretta urged unity against a common foe.

In September 1992, the mothers group and other activists gathered at Resurrection to celebrate Gov. Pete Wilson’s decision to scrap the prison. “We won the war!” they shouted.

Also at the church were some of the politicians who had ultimately responded to the activists’ persistence. Polanco, who helped negotiate the measure that Wilson signed, was there.

“Father has always been a very courageous leader and a pillar in the Boyle Heights community,” Polanco said recently. “He’s a minister who not only talks about his faith but also about social justice and environmental issues. He’s a throwback to the civil rights movement.”

Moretta and the mothers group have also been at the forefront of successful campaigns to stop the construction of an oil pipeline through Boyle Heights and a hazardous trash incinerator in Vernon. In 2017, Moretta brought Resurrection Catholic School students to speak about the rancid smells emanating from nearby meat rendering plants before the South Coast Air Quality Management District voted unanimously to take steps to address the problem.

“Everybody talks about environmental justice, and it’s real trendy now,” Villalobos said. “Father was leading the push back in the ‘80s, when nobody was talking about the concept.

But Moretta has not been able to declare victory against the lead contamination spread by a now-shuttered Exide battery plant.

A recent Times investigation noted that many Eastside homes and gardens are still polluted despite a massive effort to detoxify the area.

Moretta has spent countless hours knocking on doors to educate residents about the lead and its potential effects on their health.

He has begged those living in contamination zones to avoid being outside too long, to remove their shoes before entering the house and to follow other public health guidelines such as keeping children from touching dirt and washing their toys often.

“I remember stopping by a house a few years ago where there was a mother and a daughter making tamales in their backyard and completely unaware anything was wrong or dangerous,” he said. “It would have been bucolic if it wasn’t so devastating.”

Moretta’s hero is Pope John XXIII, perhaps best known for helping incorporate the local vernacular, instead of Latin, into Masses in 1964.

Moretta, whose Spanish is modestly accented but understandable, started Spanish-language services at his two previous parishes, St. Augustine and St. Hilary.

“Even though he’s not Latino, we feel like he’s one of us,” said Resurrection parishioner Ana Maria De Anda, 70, who credited Moretta’s church fundraisers and activities for keeping her eight children busy and away from gangs and drugs.

Rick Caruso, the billionaire developer who recently ran unsuccessfully for L.A. mayor, recalls a time in the early 1990s when homicides and gang violence were at all-time highs.

Caruso was then a member of the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners, and Moretta pleaded for more patrols and other help.

“I didn’t know who Father John was, and he reached me out of the blue with a no-nonsense call,” said Caruso, who occasionally attends Mass at Resurrection. “He said, ‘Rick, we’ve got kids dying in the streets,’ and within a matter of days, we made changes.”

His work steering kids in a positive direction has continued through the years. In the mid-2000s, Moretta secured funding for a federal gang reduction program, known as Community Law Enforcement and Recovery, or CLEAR, which provided for more officers on the streets as well as counseling, tutors and job placement for local youths.

Most Monday evenings, as he has for decades, Moretta hosts a community watch forum at Resurrection.

At one forum in early March, he gleefully scarfed down two jelly doughnuts from the boxes he had brought.

Dressed all in black — a puffy rain jacket, slacks and tennis shoes — Moretta listened as Villalobos, his longtime ally, spoke about Exide.

“You don’t hear politicians talking about it anymore, and, maybe most troubling, our youth aren’t interested,” Villalobos said. “The whole discussion about social justice has shifted to affordable housing and homelessness, and Exide has been let off the hook.”

Marquez of Mothers of East Los Angeles said her work has gotten more difficult since Exide declared bankruptcy in 2020.

“We’ve questioned their contractors in charge of cleanup, but Exide keeps changing them, and it’s difficult to know who to contact,” Marquez said. “It’s frustrating, but the work continues.”

Moretta is focused on testing residents for lead poisoning and studying long-term consequences, such as cancer and long-term learning disabilities.

Moretta told the dozen or so people at the meeting that blood testing can only detect lead for 36 days after it has entered the body. He has been advocating for non-invasive bone testing that can detect trace amounts introduced years or even decades ago.

Seven years ago, as he neared the mandatory retirement age of 75, Moretta asked the Archdiocese of Los Angeles to let him continue indefinitely. He said he views his job as “an assignment for life” and wants to keep going as long as he can “still move and still serve.”

“It’s easy to recognize that we have so many things working against us as a community,” Moretta said. “What matters, though, is how we proceed and how we lift the burdens of others.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.