Gov. Newsom unveils sweeping plan to speed up California infrastructure projects

Surrounded by hard hat-wearing construction workers at a solar energy project in the Central Valley, Gov. Gavin Newsom unveiled a sweeping package of legislation and signed an executive order Friday to make it easier to build transportation, clean energy and water infrastructure across California. The governor said the proposal intends to cut through bureaucratic hurdles that have stymied grand public works projects and will help California capitalize on an infusion of money from the Biden administration to boost climate-friendly construction.

Newsom’s proposal aims to shorten the contracting process for bridge and water projects, limit timelines for environmental litigation and simplify permitting for complicated developments in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and elsewhere.

Altogether, administration officials hope the package could speed up project construction by more than three years and reduce costs by hundreds of millions of dollars — efforts they say are necessary to achieve the state’s aggressive climate goals.

But it quickly garnered criticism both for going too far in weakening the state’s environmental protections and not far enough because it limits proposed reforms to select projects.

Newsom characterized the proposal as essential to restoring trust that government can improve people’s lives, especially under the threat of climate change.

“The question is, are we going to screw it up by being consumed by paralysis and process?” Newsom said. “We’re here to assert a different paradigm, to commit ourselves to results.”

Here’s what you need to know about Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan to offset California’s $31.5-billion budget deficit.

Newsom’s effort is the latest foray in decades-long debates over quickening the state’s sluggish process for building major infrastructure. Major reforms have often failed amid disagreement by environmental, development, local government and labor interests that are influential at the Capitol.

Newsom’s plan consists of 11 bills that he wants to fold into the 2023-24 state budget, which must pass the Legislature by June 15. Lawmakers are currently negotiating the final details of the fiscal blueprint with Newsom’s office.

State Senate Leader Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) said she agreed with Newsom’s goals, but was noncommittal about embracing the package.

“The climate crisis requires that we move faster to build and strengthen critical infrastructure,” Atkins said in a statement. “We look forward to working with our colleagues in the Assembly and administration to ensure we can do so responsibly, and in line with California’s commitment to high road jobs and environmental protection.”

At the center of Newsom’s plan is the California Environmental Quality Act — a polarizing 1970 law credited for helping preserve the state’s natural beauty but often criticized for miring needed housing, energy and transportation projects in litigation.

The proposal does not make major changes to the law, which requires public officials, agencies and developers to broadly consider and make public a project’s effects on the existing environment. Rather, it attempts to limit how long environmental lawsuits can drag out in court.

A 50-year-old California law has stymied bike lanes, affordable housing and now enrollment at UC Berkeley. But major changes in the law are unlikely.

The proposal aims to prevent any lawsuit against certain water, transportation, clean energy, semiconductor and microelectronics projects from lasting longer than nine months.

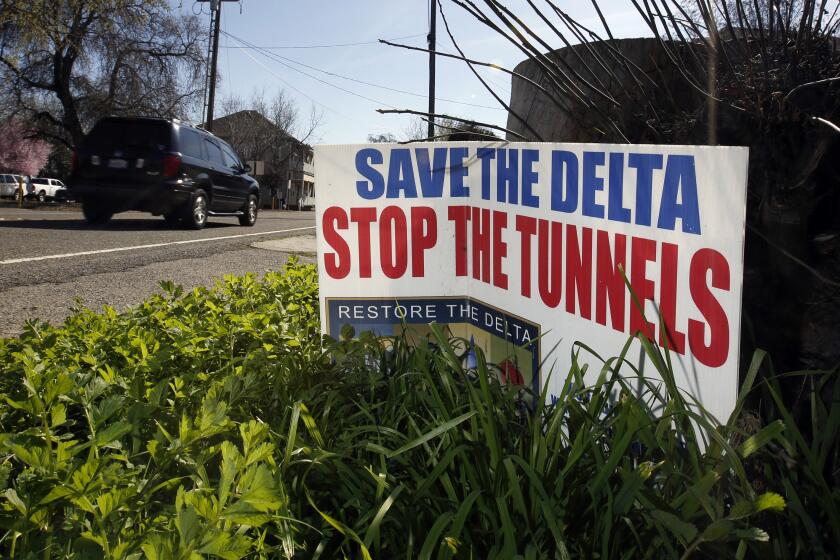

Qualifying projects, administration officials said, would include the governor’s $16-billion plan to build a tunnel to transport water to Southern California beneath the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, water recycling and desalination plants, solar fields, offshore wind farms and energy transmission.

The idea is similar to procedures already in place that have helped expedite the construction of NBA arenas in San Francisco and Sacramento as well as other megadevelopments across the state.

“I love sports,” Newsom said. “But I also love roads. I love transit. I love bridges. And I love clean energy projects like the one we’re seeing here. It’s not just about stadiums. And we’ve proven we can get it done for stadiums. So why the hell can’t we translate that to all these other projects?”

Additional CEQA changes in the plan would give government agencies greater control over deciding what’s needed in a project’s official administrative record and overturn a recent appellate court decision that required the inclusion of internal emails as part of that record. Litigation on the email issue involving a large residential and commercial development proposal in San Diego County lasted nearly two years after it was approved.

A California water advocacy group is criticizing Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed Delta Conveyance Project, saying it would be a fiscal disaster.

The governor’s ideas have spurred disparate reactions. Laura Deehan, state director for Environment California, appeared alongside Newsom at the news conference. She said that her organization and others support the governor’s broad goals of quickening construction of infrastructure needed to meet environmental goals.

“We agree that we’re going to need some large scale solar,” Deehan said. “We’re going to need some offshore wind. The current rate is too slow and we need to figure out how to speed it up.”

But she said she has yet to read Newsom’s proposed legislation and urged caution.

“We don’t want to change 50 years of environmental protection law overnight and live to regret it,” Deehan said.

Others have already made up their minds.

Barbara Barrigan-Parrilla, executive director of advocacy group Restore the Delta, which is opposed to the tunnel, said that Newsom’s plan “guts” environmental review for the project.

“Governor Newsom does not respect the people in communities that need environmental protection,” Barrigan-Parrilla said in a statement.

Meanwhile, Assembly Republican Leader James Gallagher said that Newsom should focus on more fundamental changes that could benefit all public works and other developments in the state.

“Rather than piecemeal exceptions for stadiums and pet projects, it’s time for across-the-board reforms,” said Gallagher, who represents Yuba City.

Newsom said it was essential to make changes now because of the $180 billion in state and federal funds expected to be available for infrastructure in California over the next decade, an amount boosted by allocations from President Biden’s signature infrastructure and climate change laws.

The governor likened that investment to those made in the state during its historic period of infrastructure investments in the 1950s and ’60s.

The bill is expected to create thousands of jobs in California, Gov. Gavin Newsom said.

To kick-start this process, Newsom also signed an executive order Friday that will instruct various government agencies to work together and create an infrastructure strike team, which in theory will target projects that need to be completed and make sure they get across the finish line.

The newly available federal dollars include many clean energy and other competitive grants. For California to win, it needs to show the federal government that it can deliver, the governor said.

Newsom, a Democrat, said those investments are in jeopardy if discussions in Washington over whether to raise the debt limit sour.

GOP House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) said Republicans would only agree to raise the limit if Biden agreed to roll back certain provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, which includes ambitious climate plans and funding for infrastructure projects.

“If Kevin McCarthy has his way, that’s going to set us back,” Newsom said at an event in Sacramento previewing his plan Thursday. “What he’s promoting would have devastating impact on our progress.”

The California Air Resources Board has released its long-awaited scoping plan, a roadmap for the state to drastically cut its carbon emissions.

Newsom was accompanied Friday by former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who the governor had appointed as state infrastructure czar last year.

The permitting proposals were predicated on a report that Villaraigosa and nonprofit California Forward released Thursday recommending the changes. Villaraigosa said that he had spent months meeting with labor, environmental and community groups gathering input on how to improve contracting for large public works efforts.

“What everybody said almost with unanimity: We could do this faster. We could do this smarter. We could do this better,” Villaraigosa said.

Other elements of Newsom’s package would ease contracting barriers that state agencies run into when starting and finishing their projects.

Newsom wants to allow the state Department of Water Resources and the California Department of Transportation to use a more flexible contracting process for up to eight complex projects each, which could streamline construction and reduce logistical snafus that cause delays. Another proposal would allow the transportation department to use a simpler job contracting model that could cut months off of a project’s timeline.

The departments could use these streamlining tactics to more quickly build bridges or modernize dams, repair aqueducts or maintain the state highway system. The package would also expedite three planned wildlife crossings along Interstate 15 in San Bernardino County.

The final part of Newsom’s plan would streamline Caltrans’ environmental mitigation efforts and permitting for projects that affect endangered species or are within the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta.

The proposals are unlikely to revolutionize the state’s infrastructure construction process, said Ethan Elkind, director of the Climate Program at Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment. Elkind said certain aspects of the process tying up projects are indefensible, citing that the state has spent $1 billion solely on environmental documents for its high-speed rail project.

But he expressed concern that short-cutting judicial review for the state’s biggest public works efforts could backfire.

“If there’s ever a time when you want to get CEQA right, it’s the massive tunnel affecting our entire water project,” Elkind said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.