Projected losses from a major California earthquake soar. What’s behind seismic inflation?

SAN FRANCISCO — The expected annual cost from earthquake damage for California is climbing sharply amid an increase in property values and better understanding of how soft soils could result in greater damage during shaking.

California is projected to lose an average of $9.6 billion a year from earthquake damage, the new estimates show. That’s a 157% increase from the last estimate, in 2017, when the price tag was $3.7 billion a year, according to a new report from the U.S. Geological Survey and the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

“In any given year a big earthquake strikes ... you can easily anticipate a $100-billion loss,” USGS research structural engineer Kishor Jaiswal, the principal investigator for the report, told The Times.

The totals underscore just how much the value of older buildings has soared in recent years, yet they remain vulnerable to major damage or collapse in the next big earthquake.

It is also a sober reminder of the seismic toll facing California. After the state’s other major earthquakes — the 1906 in San Francisco, 1933 in Long Beach, 1989 in the greater San Francisco Bay Area and 1994 in Northridge — it took years, if not decades, for cities to recover, and massive costs had to be paid not only by governments and insurers but also individuals who were never made whole.

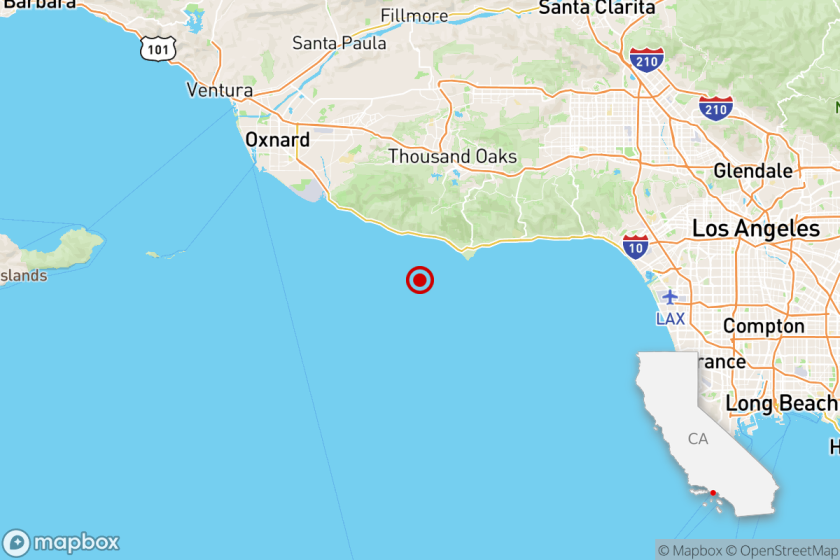

According to the new report, Los Angeles and Orange counties share the highest price tag of any metro area in the nation, with a combined projected average annual loss of $3.3 billion a year. In second place is the San Francisco-Oakland-Berkeley metro area, with a projected loss of $1.8 billion a year.

The seismic price tag for California is about 65% of the nation’s annual earthquake cost, which is $14.7 billion a year.

The projected annual average earthquake losses in other areas of California include $1.3 billion for Riverside and San Bernardino counties, $917 million for the San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara metro area, $285 million for San Diego County and $220 million for Ventura County.

Assuming the yearly earthquake loss projection remains the same, over the course of three decades, California is projected to lose $288 billion from earthquake damage. Such a figure is consistent with recent earthquake scenarios, such as a magnitude 7.8 earthquake on the southern San Andreas fault or a magnitude 7 earthquake on the Hayward fault.

Of that total, the five-county Southern California region — L.A., Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura counties — would lose nearly $150 billion. And the nine-county San Francisco Bay Area would lose roughly $90 billion.

“It’s a sobering reminder about why we need to prepare for those rare but large earthquakes, as just one major event can eclipse the costs of the more frequent but smaller ones,” USGS Director David Applegate said in a statement.

The authors of the report calculated an “annualized” earthquake loss to average out the cost of earthquake damage on a yearly basis.

It’s similar to how car insurers calculate the premium people pay yearly: People might be in a collision once every few years, but insurers calculate a yearly bill for drivers that takes into account the annual average projected cost of future collisions. How much the yearly car insurance premium will be can vary, depending on factors such as the driver’s age, accident history and the type of vehicle driven.

The magnitude 6.7 earthquake that hit Northridge in 1994 caused as much as $20 billion in damage and more than $40 billion in economic loss, “making it the costliest earthquake disaster in U.S. history,” according to the California Geological Survey.

And the damage from that earthquake, centered in the suburban San Fernando Valley, pales in comparison to the destruction that a major quake centered beneath older neighborhoods, such as in downtown L.A., would cause.

Officials have identified 33 buildings owned by Los Angeles County as having a flaw that could cause them to collapse in a major earthquake.

The 1994 earthquake’s magnitude was relatively moderate. By contrast, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake would produce 45 times more energy, and such a temblor hasn’t hit Southern California since 1857 and Northern California since 1906.

The world’s last magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck in February, resulting in strong shaking in Turkey and Syria. More than 50,000 people died.

Much like Los Angeles, Istanbul is facing a double crisis — a severe housing shortage and extreme earthquake risk — leaving residents in a bind.

A significant portion of California’s buildings constructed in the 20th century are vulnerable to earthquake damage or collapse. Retrofitting them now would leave cities far more resilient — keeping people alive, homes intact, and workplaces and neighborhoods functional.

The state’s rise in property values could enable some owners to use the equity they’ve accumulated to finance retrofits, experts say. A retrofit now can cost far less than repairing extensive damage after an earthquake, which could leave a building so wrecked it might need to be replaced.

Some cities in California have required property owners to retrofit certain types of vulnerable buildings. A Los Angeles law passed in 2015 requiring that apartment buildings with flimsy first stories — often used for carports — be strengthened has resulted in retrofits of more than 8,700 out of 12,400. That’s a completion rate of 70%. An analysis estimated that at least $1.3 billion was spent on those retrofits.

It was three days before Christmas when a magnitude 6.5 earthquake rocked the Central Coast in 2003.

FEMA and state officials have worked to make grants available for retrofits. Homeowners in certain ZIP Codes in Los Angeles, Pasadena, San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley can apply for retrofit grants of up to $13,000 through the end of May to strengthen “soft-story homes,” where there’s a top-heavy living space built over a garage that is vulnerable to collapse in an earthquake.

“This study reinforces the nation’s need to be proactive about making communities safer from threats like earthquakes,” FEMA Deputy Administrator Erik Hooks said in a statement. “This includes adopting the latest seismic building codes and investing in earthquake resilience projects.”

But many other cities in California have not acted to require retrofits. And even in L.A., city officials have yet to address the potential seismic risk of older steel-frame high-rises built before the 1994 Northridge earthquake. The USGS has said that it is plausible that five steel-frame buildings in Southern California could collapse in a hypothetical magnitude 7.8 earthquake on the San Andreas fault, and 10 could be so damaged that they would be no longer safe to occupy.

The defect that can cause single-family houses to collapse has received little attention until now. Some California homeowners will soon be able to apply for grants to help pay for the retrofit.

Some cities remain far behind. Much of the Inland Empire, which covers Riverside and San Bernardino counties, still has many older brick buildings that are not retrofitted — among the highest-risk structures in an earthquake. They can collapse, not only killing the buildings’ occupants but also raining projectiles onto nearby sidewalks, parking lots and roads, with the remains of brick walls hurled with such force that they could crush cars and buses.

In the magnitude 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989, a brick wall in San Francisco fell onto a parking lot, leaving cars crushed; five people died. And in a magnitude 6.3 quake that hit Christchurch, New Zealand, in 2011, falling bricks rained onto Red Bus No. 702, killing eight people, including the driver.

The number of people who need to be housed after a major earthquake could be enormous. The study estimated that a quake so large it had a 1-in-250 chance of occurring in any given year could result in more than 200,000 people needing short-term shelter in California. In an earthquake so large it had a 1-in-1,000 chance of occurring in any given year, more than 700,000 people would need short-term shelter.

The latest study also presents a more realistic picture of expected damage in places including L.A. and the San Francisco Bay Area, where many buildings are on top of basins that amplify ground motions during an earthquake, Jaiswal said. Such shaking can result in a worse outcome for tall buildings that are atop basins compared with those built directly on bedrock.

“If you have a deep basin, with sediments overlaying on the hard rock, those ground motions get amplified,” Jaiswal said.

Compared to earlier models, the latest report factors in localized softer soil and basin conditions, which contributed to the increase in the projected damage cost for places such as L.A. and the Bay Area.

Other areas that saw an increase in earthquake hazard from the previous model include the Salt Lake City area, and much of the island of Hawaii, Maui’s valley region and the southern coast of Oahu.

L.A. County’s proposed earthquake rules would require certain older concrete buildings in unincorporated areas, and those owned by the county, to be retrofitted.

The Seattle area was estimated to have an annual earthquake loss of $781 million; the Portland, Ore., area, $403 million; the Salt Lake City area, $174 million; the Memphis, Tenn., area, $131 million; and the New York City region, $49 million.

The fact that earthquake risk exists in areas of the Eastern U.S. may come as a surprise, but such quakes can happen. A magnitude 5.8 earthquake near Mineral, Va., in 2011 caused $200 million to $300 million in damage, and necessitated $15 million in repairs to the Washington Monument.

Other damaging earthquakes in the Eastern U.S. on record include one off of Cape Ann, Mass., in 1755, estimated to be magnitude 5.9, which resulted in damage to the Boston waterfront; an estimated magnitude 4.5 quake near Petersburg, Va., in 1774, which shoved homes from their foundations and was felt by Thomas Jefferson; and an estimated magnitude 7 quake near Charleston, S.C., in 1886 that killed 60 people, according to the USGS.

Once considered politically impossible because of cost, requiring owners to retrofit their buildings gets overwhelming support from L.A. residents.

In the early 19th century, there were three large earthquakes in the New Madrid seismic zone, around the area along the Mississippi River where Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri and Arkansas meet. The largest earthquakes were a magnitude 7.5 in December 1811, a magnitude 7.3 in January 1812 and a magnitude 7.5 in February 1812.

“Earthquakes are a national problem,” the USGS said in a statement.

New York City has a low probability of a damaging earthquake, but one that occurs could still cause significant damage because of the city’s density and the age of its buildings, according to the city’s emergency management agency. One big risk for New York City is a large number of older brick buildings that have not been retrofitted.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.