Viral estate sale bears (chaotic) witness to the downfall of a corporate girl-boss brand

Some came seeking glory. Others, a velvet couch or a La Marzocco espresso maker.

But most shoppers who flocked to the viral estate sale at the Wing in West Hollywood over the weekend were there simply to bear witness, as a brand built on the aspirations of Instagram was dismembered by the vultures of TikTok.

“I used to take meetings here,” said Caroline Wimberly, 29, who spotted the sale on the popular video app. “Even if things are out of budget, it’s a spectacle.”

With its millennial pink office furniture and $13 “Fork the Patriarchy” grain bowl, the Wing was once a byword for women’s ascendant economic power, a femme-focused WeWork whose girl-boss aesthetic and skirt-friendly climate control defined corporate feminism.

At its West Hollywood outpost — one of the company’s 11 clubs — members paid upward of $250 a month for frosé on the terrazzo-checkered terrace and tête-à-têtes with Hollywood stars. The Wing promised a heady mix of sun salutations, power lunches and drop-in day care, with zippy Wi-Fi and a powder room stocked with Chanel perfume, organic tampons and Honest Co. diapers.

But the COVID-19 pandemic decimated women’s professional progress, and the brand foundered amid damning allegations of discrimination, dysfunction and a toxic work culture.

Now, the club itself was being liquidated, its bespoke furniture, industrial kitchen equipment and high-end ephemera luring bargain hunters from across Southern California.

In a matter of seconds, the spectacle turned to blood sport.

“It’s like the ‘Hunger Games’ out here,” 32-year-old Ayrn Terry cried out as she tried in vain to extricate herself from between branded yoga mats and tongue-in-cheek athleisure.

For many of the 20- and 30-something shoppers, these talismans of corporate feminism didn’t just feel cringeworthy, but myopic and willfully naive. Maybe it was easier to tear apart the evidence than to acknowledge they’d once imbued those totems with power.

“It’s giving ...” artist manager Jaz Vargas paused amid the frantic crowd, searching for the right turn of phrase. “I just finished watching [the HBO zombie series] ‘The Last of Us,’ so when they go into shops and stuff and it’s, like, raided? It’s giving that vibe.”

Early birds carted off their treasures, while latecomers swarmed over boxes of stemless wineglasses and waffle-knit slippers, grabbing whatever they could carry or pry from the wall.

Already, the club’s once opulent Great Room had a whiff of the post-apocalyptic indoor pool at Grossinger’s, the abandoned Catskills resort in New York immortalized in ruin porn. (See also: the Pripyat amusement park outside Chernobyl, or Detroit’s Michigan Central Station.)

“I wasn’t fully mentally prepared,” said Leslie Smith, 30, as she guarded her basket of sage-and-blue open-knit blankets. “Watching people come in, it felt like Black Friday.”

For many, chaos was the point.

“It’s the fall of Saigon for girl bosses,” said Nick Nardini, 36, with barely contained glee.

Even as he spoke, others were filming the melee for TikTok. Like the borscht belt ruin, its decay had become its allure.

“People are eating this up like vultures,” said former employee Yari Blanco, 36, as she hunted for a souvenir from the carefully curated bookshelf. “People used to always joke, ‘Whenever they’re selling the furniture, let us know.’ And here they are, true to their word.”

Blanco looked apiece with the other scavengers in her Adderall-blue lounge set, topknot bun and Dior cat-eye glasses. But her melancholy set her apart.

“This is a little piece of history for me,” she said. “If I can walk away with a tote and maybe some things that my former colleagues worked on, that’s something I’d like to keep.”

Blanco acknowledged the club’s failures — brought on, she felt, by the pressures of venture capital — but was unsettled by the gleeful dismantling of so many women’s invisible labor.

Take this library: It had been someone’s job to find these books, to buy them and arrange them in an Instagrammable rainbow, a statement that was more than the sum of its titles: Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Lowland,” Patricia Highsmith’s “Nothing That Meets the Eye,” “Frida: A Biography,” “The Norton Book of Women’s Lives.”

If the Wing was a shorthand for female aspiration, the bookshelf was a visual symbol of the brand. Ali Wong had posed here. Halle Berry, Maggie Gyllenhaal — even Vice President Kamala Harris had glad-handed in front of this bookshelf, back when she was still a California senator chasing the Resolute Desk.

“It’s interesting to watch this curated library of female authors and see people sort of staring at it and saying, ‘I don’t know what to do with this. Do I take these books? Are they valuable?’” mused 33-year-old marketing manager Candice Gutierrez as she shopped among the leftovers.

Like Blanco, she was both clear-eyed about the company’s failures and distressed to see it so grotesquely unmade.

Aside from a couch reupholstered in blue as part of an abortive, mid-COVID rebrand, the space itself was mothballed in an era when Roe vs. Wade was the law and Harris, Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar were vying to be the first Madam President.

Three years later, women had just recovered their share of the workforce. And working mothers — a core of the Wing’s demographic — still lagged behind. Millions now also lived in states without access to lifesaving reproductive care, and medication abortion hung on a Trump-appointed judge in Texas.

“It was just so wild to see this go from an exclusive membership club to now people are literally running through here taking furniture and lights off the walls,” said former member Amber Phillips. “It’s a good metaphor. But it’s very literal.”

She pulled billionaire Arianna Huffington’s 2014 self-help manifesto “Thrive” off the bookshelf, displaying it to Saleh Greaux and their Chihuahua, Papa Bear, as evidence of the ambient symbolism.

“I wonder what this could have been with a real politic, with the people who make culture a part of it instead of using us to cosign this,” she mused. “I’m just kind of shook.”

Others were less wistful.

“I don’t feel any sadness or remorse seeing this happen,” said former member Bianca Maxwell, 33. “It just feels appropriate that this is the end of things given how they treated the people who helped build it.”

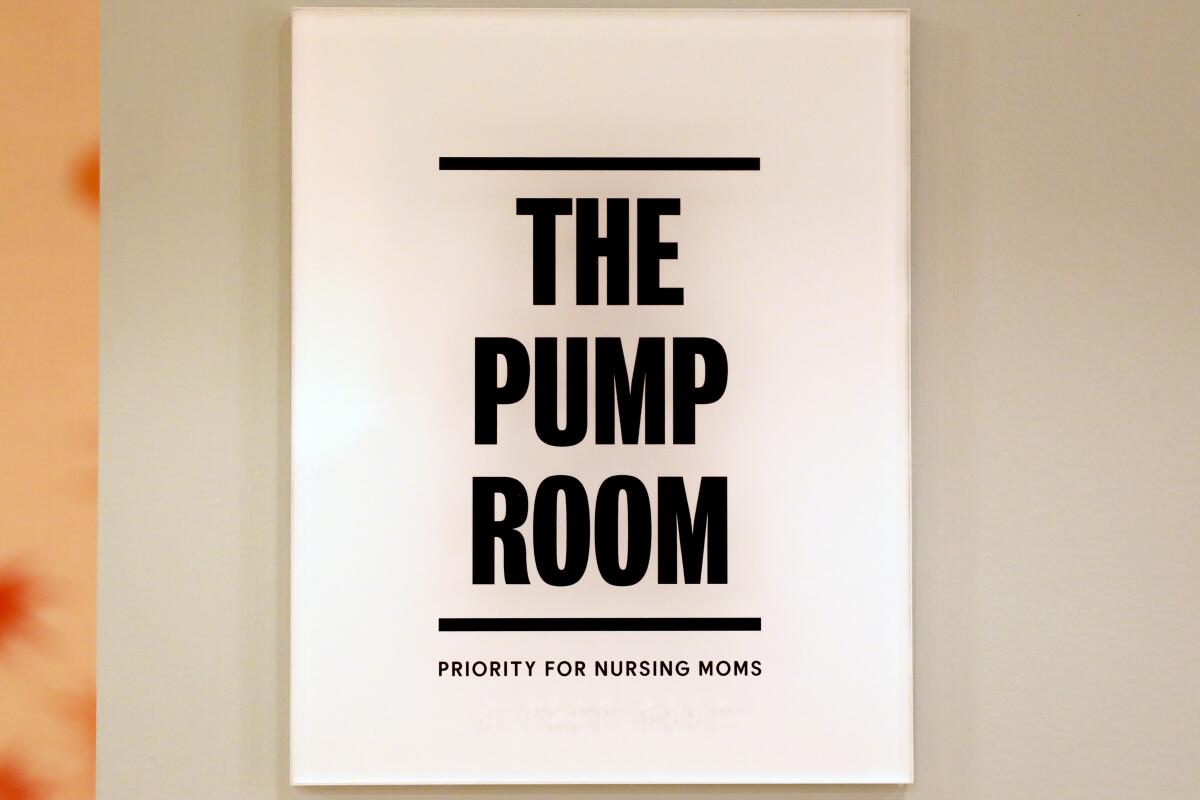

But Gutierrez, the marketing manager, saw something else. Everyone wanted a cane chair or a marble-topped bistro table, she noticed. No one cared about the day-care center’s hand-painted dollhouse or the hospital-grade Spectra breast pump in the bathroom.

“It’s weird to materially take down the aspirations of this place,” Gutierrez said as she waited to pay for her haul. “The fact that women had to leave the workforce, that so much of the labor of keeping society together was put on women, and here it’s being directly disassembled.”

She looked around — at the mountain of unused thermometers, the World’s Best Mother T-shirts and fake plastic succulents and the “I’ll have what she’s having” sign above the bar where a thousand oat milk lattes were served.

“But I did get a robe.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.