California’s ‘phantom lake’ returns with a vengeance, unearthing an ugly history of water

A winter of epic snow and rain had brought California’s “phantom lake” back to life — and threatened towns and farms in the process.

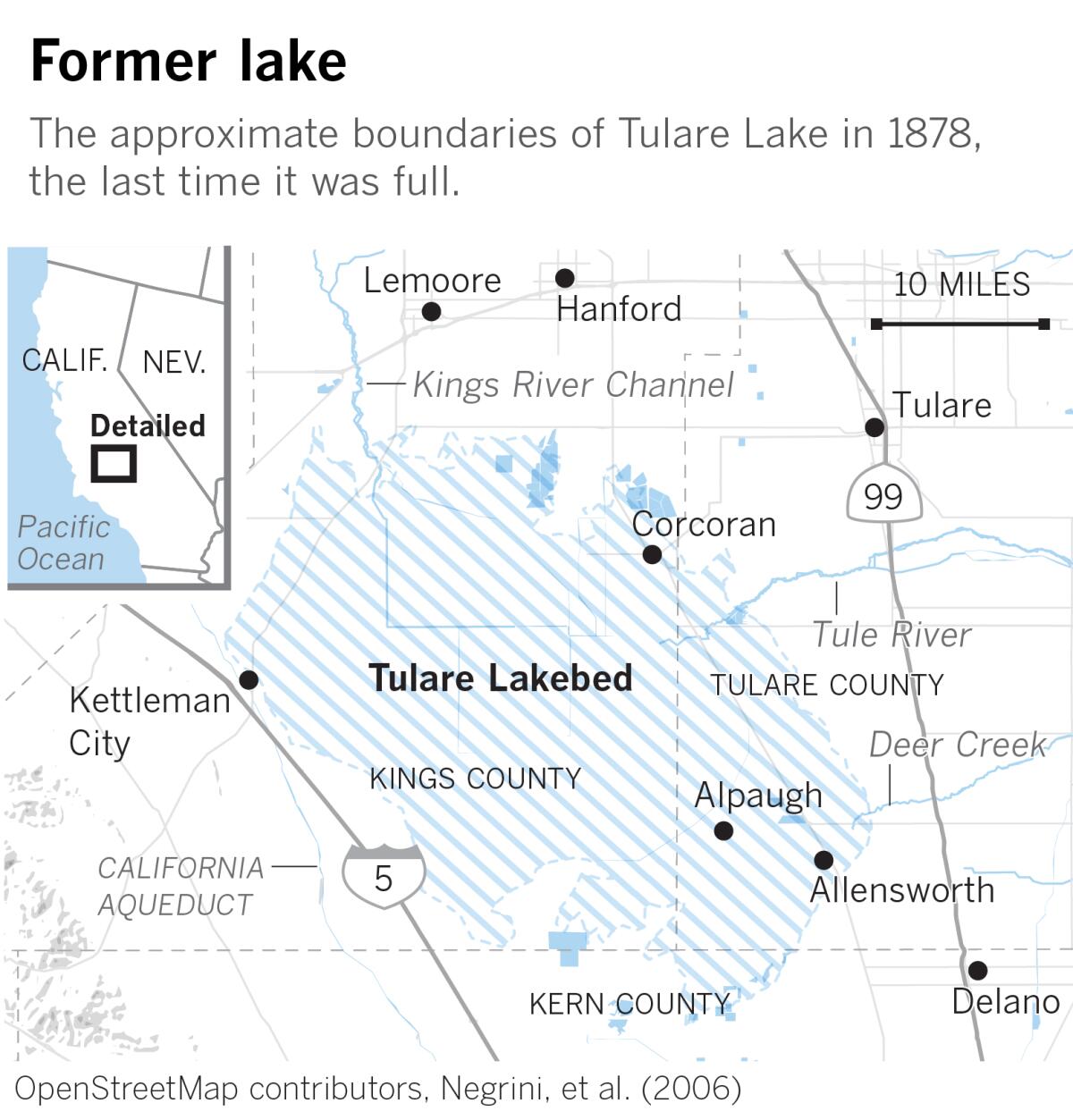

Once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River, Tulare Lake was largely drained in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the rivers that fed it were dammed and diverted for agriculture.

This month, after powerful storms, rivers that dwindled during the drought are swollen with runoff from heavy rains and snow, and are flowing full from the Sierra Nevada into the valley, spilling from canals and broken levees into fields.

Here is a history of Tulare Lake from the pages of The Times.

What is the history?

This is not the first time Tulare Lake has reemerged. It also happened in 1997, another epic rain year. But officials say it was 1983 when the lake last reached a high point, amid heavy rain and snow runoff that submerged about 82,000 acres.

“Every 15 years or so, in the wake of a record winter storm or heavy spring snowmelt, the dams and ditches cannot contain the rivers. When that happens, the great inland sea, at least a hint of it anyway, rouses from its slumber,” Mark Arax wrote in The Times that year.

As historic storms fill once-dry Tulare Lake and submerge prime California farmland, tensions are building over how to handle the swiftly rising floodwaters.

Arax described the history this way:

Halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco, this basin has a strange, slightly menacing feel, wet or dry. While it qualifies as desert, averaging less than 10 inches of rain a year, it also happens to sit at the foot of one of the nation’s most generous watersheds, the Sierra Nevada snowpack.

Before agriculture subdued the mountain rivers, much of the southern San Joaquin Valley was transformed each spring into marsh teeming with tule elk and antelope, honkers, and gray and Canada geese. No land sat lower than this basin, the terminus of the Tule, Kaweah, Kings and Kern rivers.

Floods: Rivers tamed for agricultural use overflow into bed of once-great inland sea.

The shallow lake that sprang from their waters — dubbed La Laguna de los Tulares by Spanish explorers — covered more than 1,200 square miles, bigger than the Great Salt Lake. On rafts and canoes made from the thick tule reeds, Yokut hunters fished for salmon, perch and sturgeon while the women waded far into the waters to dig for clams and mussels.

So bountiful was the harvest that white settlers named the area Mussel Slough, and commercial fishermen in the 1870s plied the lake in schooners and steamers and caught terrapin turtles served as delicacies in San Francisco restaurants.

Visitors never forgot the roar of the big birds alighting.

“An immense body of wild geese whose wings and cries as they moved from place to place caused this kind of roaring noise,” wrote Charles Nordhoff, a New York journalist who penned one of the first travel books about California in 1873. “A noise like the rush of a distant railroad train.”

In 1880, in the name of reclamation, the state Legislature allowed newcomers to buy marshland for $2.50 an acre, $2 of which would be refunded if they helped construct a levee system. This touched off a decades-long stampede of “sandlappers,” the derisive name given farmers who cultivated swampland.

Tulare Lake may have continued to turn up blue on most maps but it was pretty much a mirage.

Arax wrote more about Tulare Lake.

What is happening now?

As The Times’ Ian James and Susanne Rust reported, Tulare Lake’s sudden reemergence has fueled conflict in one of California’s richest agricultural centers, as the spreading waters swallow fields and orchards and encroach on low-lying towns.

In a region where the major agricultural landowners have a history of water disputes, the floods streaming into Tulare Lake Basin have reignited some long-standing tensions and brought accusations of foul play and mismanagement.

People in the rural California community of Allensworth have been fighting floodwaters by building berms, and are bracing for the next storm.

Residents in rural towns such as Alpaugh and Allensworth fear their homes won’t be prioritized for protection from the rising waters. And as the water has overwhelmed canals, tensions have flared over where the floods should be directed, and which farmland should go under first.

The view of native Californians

In satellite images of the San Joaquin Valley, the footprint of the old lake bed stands out as a darker, grayish area in the patches of farmland. In the days before the damming of rivers, the lake could stretch for 790 square miles, four times the size of Lake Tahoe, with depths of 30 feet.

Before white settlers arrived in the Central Valley in the 1800s, Tulare Lake was the center of life for the Native Yokut people who lived by its shores and along the rivers. Then farmers began diverting water and claiming land in the lake bottom.

More than a century later, members of the Santa Rosa Rancheria of the Tachi Yokut Tribe live near what was once the lake’s north shore. The tribe’s leaders have agreed to diversions that will channel some of the floodwaters onto their lands, easing pressure on the system while helping to recharge groundwater.

A California Historic Park commemorates life in Allensworth, a Central Valley town founded after the Civil War where Black residents could prosper.

The lake’s rise is “just a very small reminder of what was once here,” said Leo Sisco, the tribe’s chairman.

The phantom lake, which the tribe calls Pa’ashi, remains central to its spiritual beliefs. Its traditional songs include passages that say when the water rises, “that’s the lake telling us, ‘OK, it’s time for you guys to get out of here now,’ ” said Robert Jeff, the tribe’s vice chairman.

“So that’s when our people would pack up,” Jeff said, “and we’d head to the mountains, to our other villages, until the water receded.”

“It’s time to move to higher ground,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.