If a lightbulb burns out at the preschool where she works, Bernice Young climbs a ladder to change it. If playground trees shed their leaves, she comes out with the leaf-blower. She mops the restroom stalls and shampoos the classroom carpets. For generations of 2-to-5-year-olds who call her Miss Bernice, she has brought the blankets for nap time and Cheez-Its for snack time.

After 23 years of custodial work in preschools from Hollywood to South Los Angeles, she said, her pay has climbed from $10.01 an hour to $18.86 an hour. It is barely enough to make the rent on a $2,000-a-month one-bedroom apartment she has found.

“My hands are bad. My knees are bad. My legs are bad. But I come to work every day,” said Young, 58, who works at Esther Collins Early Education Center on 52nd Street in South Los Angeles. “I love my job but the pay is horrible and it’s been horrible for many years.”

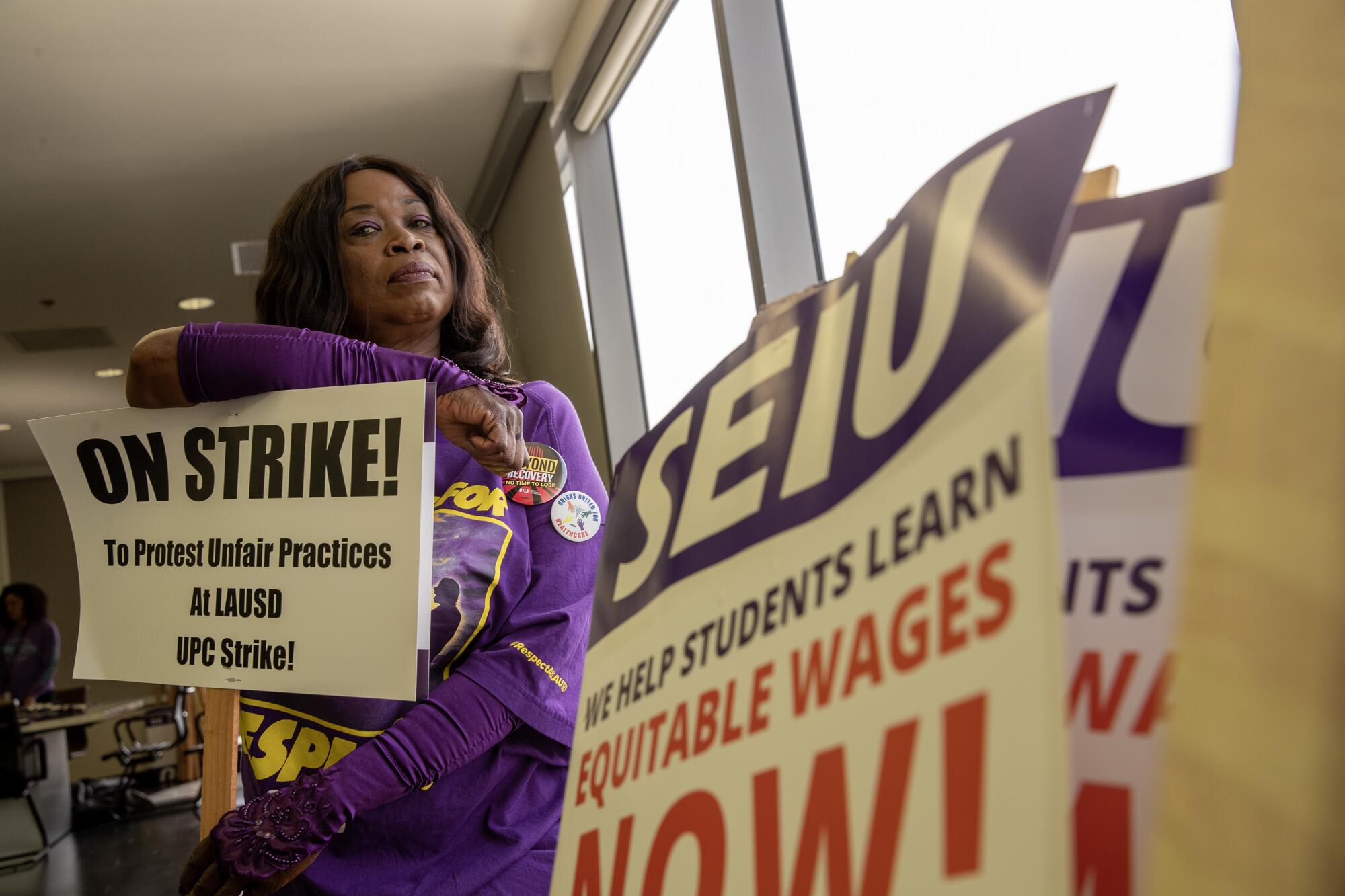

At Los Angeles Unified, the nation’s second-largest school district, she’s part of a legion of employees — from bus drivers to teacher’s aides, food servers to janitors — who serve schools in the background and are in many ways the essential workers of campus operations. Her 30,000-member union is preparing for a three-day strike on Tuesday in their drive for higher wages and will be joined by teachers in solidarity.

With most employees expected to be gone, the district is keeping its 420,000 students off campus and providing no live instruction, although all employees will be able to report to their job sites.

Young’s union, the Service Employees International Union Local 99, is pushing for a 30% pay hike plus an additional $2 per hour for the lowest paid workers.

On Friday the district increased its offer to Local 99, presenting a 19% ongoing increase over three years and a one-time 5% bonus for those who worked in the 2020-21 school year. The district also launched a last-ditch legal effort late Friday with California labor regulators to stall or prevent the strike, but it’s unclear if a decision will be made in time, and no negotiations are scheduled before the strike date.

The teachers union, also in the midst of contract negotiations, is seeking a 20% wage increase over two years and also is bargaining for a wide-ranging list of initiatives, including extra support for Black students and affordable housing for low-income families.

The closures caught parents by surprise, sending them scrambling to find daycare or take time off work. Teachers are sending home packets of schoolwork and computers. The school district and community organizations are throwing together plans to feed tens of thousands of children who rely on schools for most of their meals during the week. Los Angeles city and county parks departments are organizing daylong activities and supervision.

What are child-care options when LAUSD schools close for a strike? Some L.A. County parks will be open, along with some city parks and even campuses.

Young, who serves as a union strike captain, works full time and has health benefits. But she regularly stays beyond her eight-hour shift to finish the chores of the day and is determined to do what it takes to improve working conditions.

“You do get taken advantage of,” she said. She is always on her feet. “All day long, honey, every day. I sit down when it’s my lunch time, my break time. Other than that, all day long.”

She said she hopes the strike sends a message.

“We don’t want to keep living in poverty all our lives,” she said. “The wages, that’s a big deal — to be working so long and to not make nothing.”

At 56, John Lewis has been driving buses for the school district for 34 years, a job that now earns him $34 an hour. He climbs onto his six-wheel yellow bus at the big Gardena depot at 5:30 a.m. and climbs off at 5:30 p.m.

On his current route, he picks up and drops off about 50 students from Bancroft Middle School and Fairfax High. He is assigned some students for six years, driving them through childhood into the cusp of early adulthood.

“I love what I do. I love being around kids. We’re the first person they see in the morning and the last person they see when they get off the bus,” Lewis said. “To see them grow, that’s amazing. ... It’s not like we wish to interrupt their education, but we have families and we want to be respected and to make a decent wage.”

The average pay for the Local 99 unit that includes bus drivers, custodians and food service workers is $31,825. The average annual pay for instructional aides, including for special education, is $27,531. Teacher assistants on average make $22,657. After-school program workers on average make $14,576.

About 24,000 Local 99 members work fewer than eight hours a day, and about 6,000 work eight-hour jobs. More than 10,000 Local 99 members do not get healthcare coverage through the school district.

Shaunn D — she didn’t want to use her last name — works at Dorsey High in South L.A. as a Black Student Achievement Program representative.

Until this year she had worked for 19 years as a community and parent representative at Bradley Elementary school, making about $16 an hour. Both jobs have involved a little of everything — a common theme among Local 99 workers who are used to filling the gaps for what’s needed.

“Sometimes they just need words of encouragement,’ she said of her students. “ Sometimes they need to just hear people — or just talk and us listen. Some of these kids are suffering and you can’t send a child to learn if they’re hurting.”

She recalled a 10-year-old who came to school after his 31-year-old mother was murdered.

“I held this boy in my arms like he was a baby, sitting in the nurse’s office, rocking him, because he couldn’t function that day,” she said. “He was so broken.”

At Dorsey, she welcomes students in the morning. Later in the day she addresses the needs of Black students.

“I have outreach with the parents. I talk to the children,” she said. “We also provide clothing or whatever the children need, if they may not have shoes, or jackets or something like that.” There’s no budget for this, but people will donate money or she’ll buy items out of her own pocket.

She said she feels bad that students will miss school. “It’s going to impact them.” But the union action is important to sustaining the livelihoods of those who want to work in public schools.

“I do this because I love the kids,” she said of her role. But she tells her own children in college — who grew up watching their mother take on second jobs to make ends meet — “Don’t get into education. And that sounds bad, I know. But I didn’t want them to have to go through the struggles.”

For 24 years, Peniana Arguelles has worked as a special education assistant in Los Angeles public schools.

At Menlo Avenue Elementary School in South Los Angeles, Arguelles feeds children who can’t hold a fork. She changes their diapers, helps them choose colors for their paintings, and gives them hugs when they cry.

Arguelles, who has worked as a special education assistant at LAUSD for 24 years, said she considers herself blessed and “loves her job and her students.” She does not have a teaching credential but serves as a teacher’s right hand, working with children who have disabilities and special learning needs.

She and other teacher assistants said their walkout is about respect. They are among the lowest paid workers in the district. Aides who worked with disabled students start at around $19 and can earn up to about $24 an hour. But they said their workload has become unsustainable.

Arguellas is particularly peeved that the Los Angeles Unified School District is asking her to do more work outside of her assigned classroom duties — helping additional students with assignments and leading calming exercises with them.

“It’s putting on two hats for the same salary,” she said. “It’s not fair.”

Kyle Sanchez, 35, works at Rosa Parks Learning Center in North Hills with 18 special education students in a fourth-and-fifth-grade split classroom. He said the class is “way too big” for just him and results in “too many off-the-clock hours.” He wants higher pay, but also a reduction in class size and help.

“We’ve reached the point where something needs to be done,” Sanchez said. “We need more staff, more money and some respect.”

These teacher assistants said the public does not understand the work their members do to keep schools functioning.

Serios Castro, 35, a “proud LAUSD product” and Roosevelt High School alumnus, said extra work for special education teachers and aides is taken for granted.

Castro created an on-campus photo club specifically for special needs students at Elizabeth Learning Center that he said established “opportunities for kids to express themselves through photography.”

“It seems like ‘going above and beyond’ is just now expected,” Castro said. “We love our kids and our school but at the end of the day, we need a living wage. We love L.A., but we also have to be able to live here.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.