A moveable feast: How the Oscars venue-hopped through Los Angeles

Over a lifetime, the typical American picks up and moves nearly a dozen times.

So the Oscars ceremony, turning 95 years old, is pretty much in the ballpark with other Americans.

In some places it’s “lived” for more than two decades. Others have been a one-and-done residency.

Beginning in 1929, the ritual has moved around the city of Los Angeles — and a couple of times just outside the city limits. Since 2002, the Oscars have settled down and settled into their “forever” home, in Hollywood — a word that for the movie-watching world summons fever dreams of Olympus, of Elysium, of Valhalla, but which in mortal geography is simply another neighborhood in the city of Los Angeles.

Take this little travelogue to Oscars venues and scenes over the decades; no tourist bus required.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

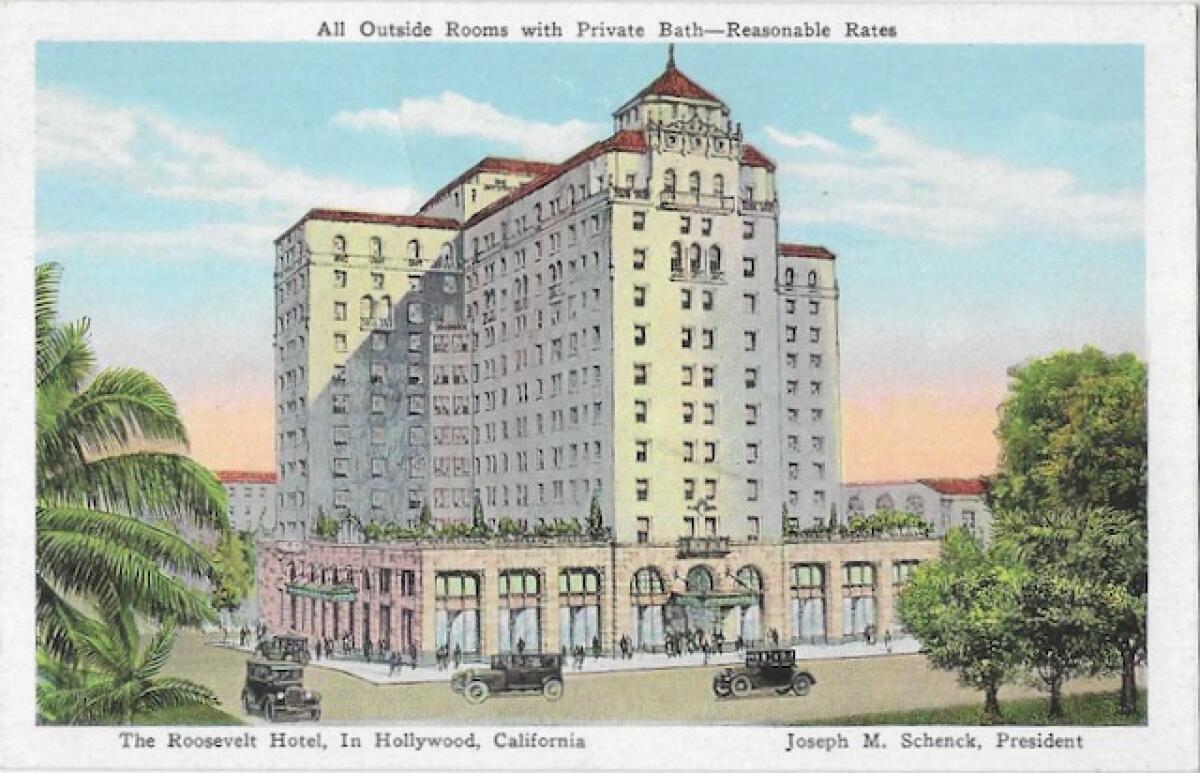

May 1929 In the Blossom Room of the recently opened Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, adorned with garlands for this new Hollywood exercise in back patting. It’s the only time the Roosevelt will host this event. Attendees sit at tables with numbers on them to help the seating plan, just like ordinary banqueting mortals, where their $5 bought them a dinner of broiled chicken or sole, green beans and ice cream and cake. There were five nominees for best actress. Three of them were Janet Gaynor, in three different movies. And the winner was … Janet Gaynor. Remember, they were just figuring this out.

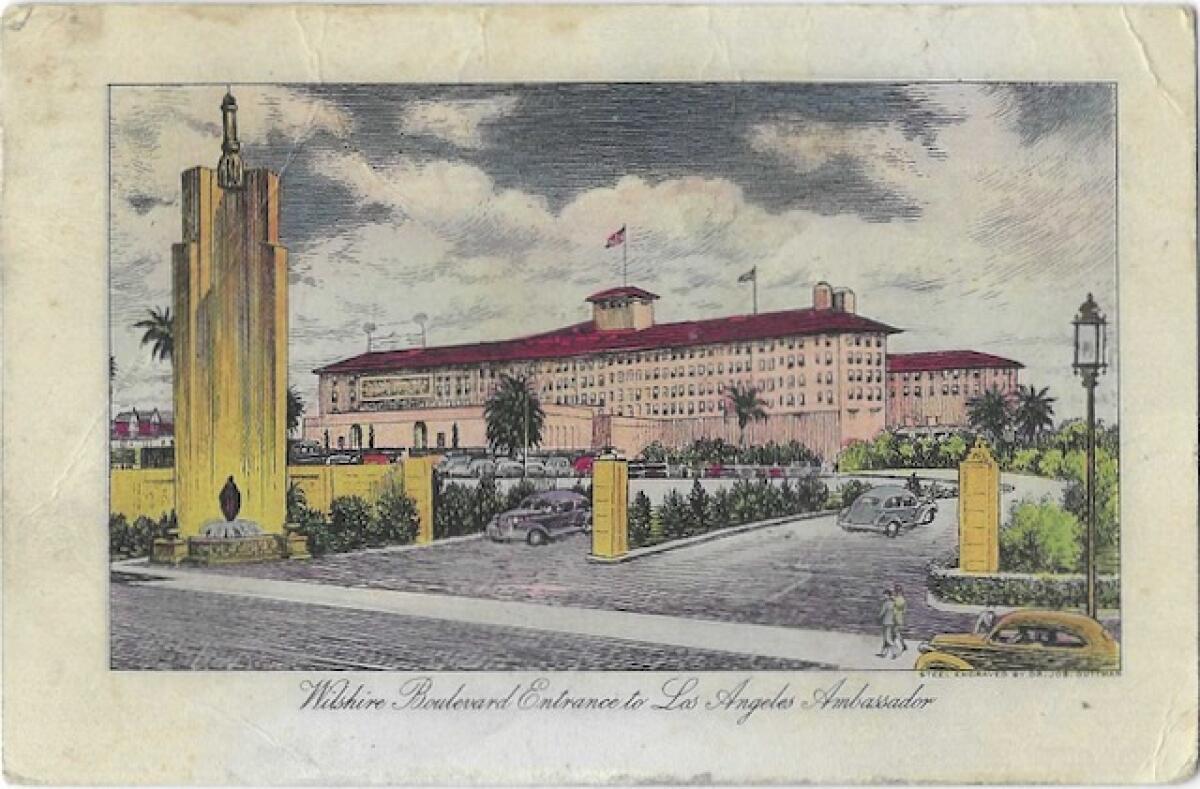

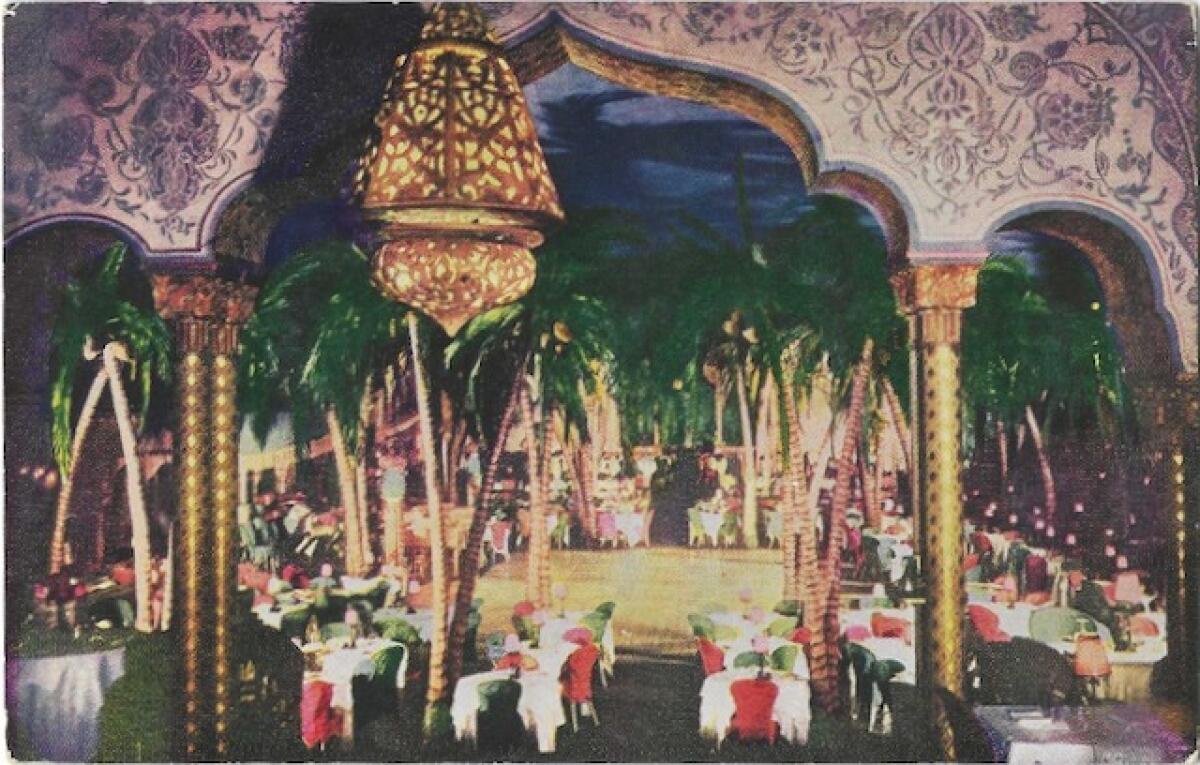

April 1930 In the Cocoanut Grove at the Ambassador Hotel, a swanky and exotic celebrity haunt, among papier-mache palm trees and monkey motifs. There were two Oscar ceremonies here in 1930. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was kind of hitching up its pants to get on a regular schedule, and for a few years thereafter the ceremony was held in November.

The most famous statue in the world is probably, maybe the Oscar. Many have been stolen, and several have been sold.

November 1930 At the Ambassador again, this time the Fiesta Room, where the guest of honor was Will Hays, a scarecrow of a man, the former postmaster general and head of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. On the heels of scandalous antics by Hollywood’s newly rich and ill-behaved, and to fend off outside regulation, Hays was brought in as the morals cop. His “Code to Govern the Making of Motion Pictures” was the studios’ official guidebook from the 1930s until 1968. In a nifty little tweak, as Hays sat there among the anointed, the best-actress winner announced that evening was Norma Shearer, for her role in “The Divorcee.” It was a classic “pre-Code” movie replete with adultery, hard-drinking and general woo-hooing of the sort that the Hays Code kept studios from making for many years to come.

November 1931 In the Biltmore Hotel’s Sala de Oro, the first of seven Oscar ceremonies to be held at the hotel and the first to be broadcast on radio (for about an hour of the proceedings). Four years earlier, movie muckety-mucks had collected here to found the academy, and here, as legend tells it, MGM’s art director, Cedric Gibbons, sketched out the Oscar statuette on a linen hotel napkin. Or a tablecloth. Whatever; napery was defaced. As best sources can determine, it acquired the nickname “Oscar” from Margaret Herrick, the librarian and then executive director of the academy, after her mother’s first cousin, Oscar Pierce, a man Herrick herself seems to have never met. Ever after, as she wrote in 1959, she “regretted more times than I care to remember” the lese-majeste of her “thoughtless quip.” It was a gift. No journalist thereafter had to write about winners of dignified-yet-clumsy “Academy Award of Merit.”

November 1932 In the Ambassador’s Fiesta Room again. It was the last ceremony for almost a year and a half.

March 1934 Once again in the Fiesta Room. The academy, skipped 1933 to rectify its calendar, the way countries switched from the awkward Julian calendar to the more accurate Gregorian calendar. The American colonies did it in 1752, simply lopping about a week and a half off September that year.

February 1935 In a Biltmore Bowl adorned with cherry blossoms. Claudette Colbert won for her role in the comedy “It Happened One Night.” Figuring that she wasn’t likely to be honored because no comedy had ever won the big gongs, on Oscar night Colbert was at Union Station, about to board the Santa Fe Super Chief to New York, when she won. She was dressed in what the fashion writers had to describe as a “chic traveling suit.” Some movie men went screaming over to the station, and as Colbert remembered it, “I was whisked back to the Biltmore to accept the Oscar while they held the train!’’’

March 1936 In the Biltmore Bowl. This is the year Hollywood turned on its masters. Screenwriter Dudley Nichols became the first winner to turn down his award, for the film “The Informer.” He was a founder of the fledgling Screen Writers Guild and was protesting the academy’s refusal to recognize it. Once the guild was established, he accepted the award. And then Bette Davis accepted her best actress Oscar for “Dangerous” wearing not a glamorous gown but a maid’s costume she borrowed from another of her films, “Housewife.” She was protesting the kind of casting she was getting at Warner Bros. That, or the Oscar, did the trick. Two years later she won again, for “Jezebel,” and accepted that award wearing a dramatic dark gown with a portrait collar made of feathers.

March 1937 and March 1938 Back at the Biltmore Bowl again, but in 1938, held a week late because epochal storms had stranded stars, execs and crew all across waterlogged L.A.

February 1939 At the Biltmore Bowl, Spencer Tracy won as best actor for “Boys Town.” In the fullness of time, he gave the Oscar to the actual Boys Town in Nebraska on the condition that the academy give him a replacement. It did; it was engraved with “Best Actor — Dick Tracy.” By this year, even the academy had started calling it the “Oscar.”

February 1940 Back to the Cocoanut Grove, for the next-to-last time at the Ambassador. Eventually, for all of its fabled history — the Oscars ceremonies; the short, illustrious stay of the Soviets’ top commie, Nikita Khrushchev, in the royal suite; and the assassination of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in the kitchen pantry — the Ambassador was torn down in 2005-06 and schools built on the site. Donald Trump had bought it, but eventually lost out when the school board pushed him right back, and a court agreed. This was also the year The Times published the winners’ names in advance, and so the next year, the academy went to the super-secret sealed-envelope system that’s become a hallmark.

February 1941 Return to the Biltmore Bowl, and again in February 1942, with a stark difference: There was a war on. Instead of their usual Oscars finery, men wore suits and ties, women wore dimmed-down dresses, and best supporting actor winner Donald Crisp wore the uniform of his U.S. Army Reserve unit. The first time he had worn an American military uniform was when he played Gen. Ulysses S. Grant In “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915. Metal shortages during the war meant winners were given painted plaster Oscars that were replaced with the real gilded bronze McCoys after the war ended.

March 1943 At the Ambassador, actress Greer Garson won as best actress for “Mrs. Miniver,” the best-picture-winning film whose propaganda value, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill supposedly said, was worth five battleships, or 50 battleships, or 100 destroyers — the numbers are muddled. Garson made the academy’s longest-ever acceptance speech, something over five minutes. There is no complete video of it. Maybe the cameramen ran out of film. In years to come, she joked that every time the story was retold, her speech got longer. But she did note quite aptly that “I’d broken a sacred rule. Leading ladies who get an award aren’t supposed to say further than ‘Thank you, thank you,’ and burst into tears.” Her Oscar was destroyed in a 1989 fire in her Los Angeles apartment, and the academy replaced it, no speech necessary. As photos on the academy website show, this was the last of the banqueting Oscars. Henceforth the divinities of the screen would sit as you and I did in a high school assembly: facing the stage, in fixed seats, drinkless. I’d hoped to learn that this change coincided with the first televised Oscars — after all, the academy would not want the dignity of the occasion to be marred by millions of TV viewers getting treated to the sight of sozzled stars, which is one of the chief delights of watching the Golden Globes. But no — the school-assembly format began when televised Oscars were still about a decade away.

March 1944 For the first time at Grauman’s Chinese Theater, across from the Hollywood Roosevelt. The awards would stay at Grauman’s for three more years, and in 1945 revert to a more formal black-tie standard for the men.

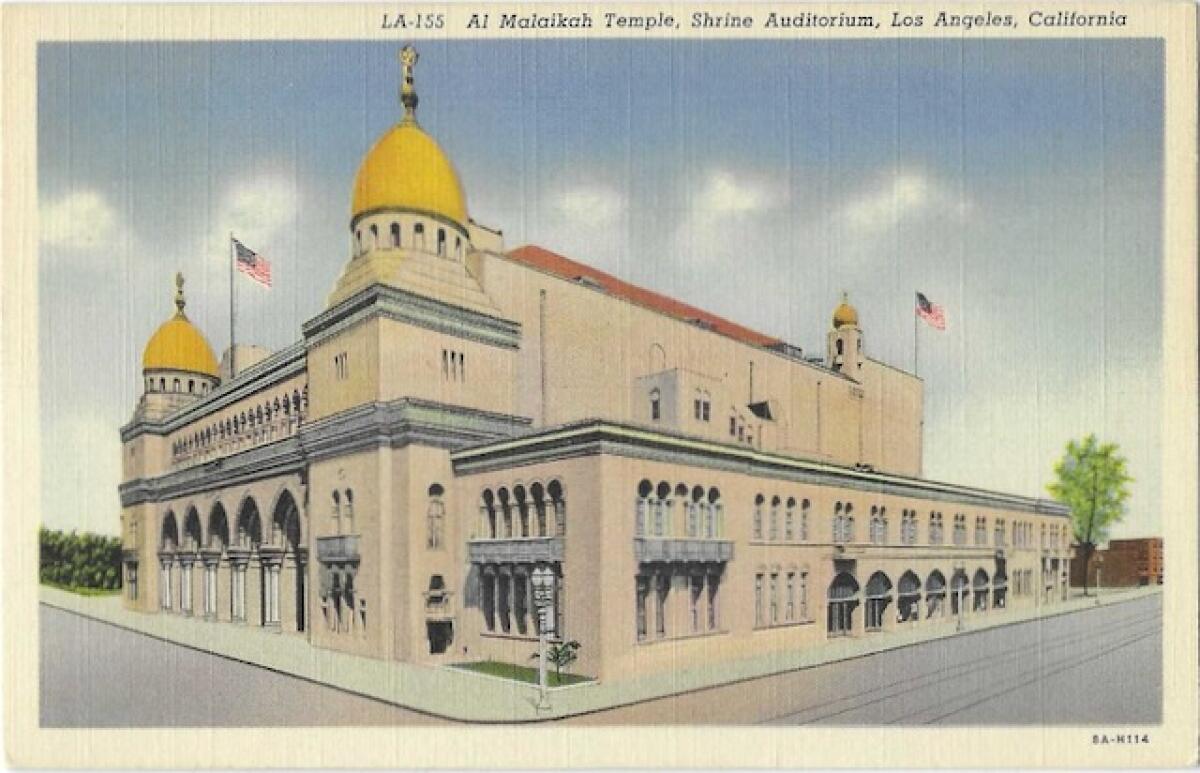

March 1947 Debuting at the massive Moorish Revival-style Shrine Auditorium near USC, whose 6,000-plus seats allowed for a huge guest list and long, long lines of limos. The original auditorium burned down in 1906; this exuberantly styled replacement opened in 1926. Its stage is where King Kong broke his fetters in the 1933 movie. The Oscars would return to the Shrine the following year.

March 1949 Well, this was awkward –- for one time only, at the Los Angeles Academy Award Theatre on Melrose, originally the Marquis Theater. The academy bought the place in 1946, and in 1949 it helped to dodge a kerfuffle. Here’s a distilled account, from the Academy Museum’s website: “In 1949, just days before the ceremony,” the academy announced it was moving the event from a studio soundstage to the Marquis Theater. There were allegations that the big studios, by underwriting recent Oscars ceremonies, were trying to influence academy voters. “Facing both bad publicity and mounting costs, the studios pulled their funding at the last minute,” which left the academy in the lurch. It hastily Ant-Manned the event and the audience — the Shrine could seat more than 6,000 people, the Marquis only 950. The task of having to say “no” to thousands of the Hollywood entitled must have been nightmarish.

March 1950 In the RKO Pantages theater, with plenty of seats once more. Around this time, in order to avoid unseemly commerce in Oscars, each winner was required to agree in writing not to sell the prized gold-plated homunculus on the open market without first offering it back to the academy for a figure ultimately set at a token $1. The Pantages would remain Oscar’s home until 1961.

March 1953 For the first time, people at home could watch the ceremony on TV. It was broadcast from the Pantages with a simultaneous New York satellite event, the cameras hopping back and forth between the coasts to follow the presenters and winners. The show collected the single largest home viewing audience to that moment in TV history, something its creators have surely yearned after ever since.

March 1956 Still at the Pantages, the renowned cinematographer James Wong Howe won for his work on “The Rose Tattoo.” He took the Oscar from host Jerry Lewis, looked it over with his craftsman’s eye, and said, “No bad side.” Why this man does not have a star on the Walk of Fame is a perpetual source of irritation to me.

March 1959 At the Pantages, something happened that would never happen again. The show went so smoothly that it ran 20 minutes short, and Lewis, the host again, had to vamp desperately to try to hit the TV network’s scheduled “out.” According to the Hollywood Reporter, he tried to conduct the orchestra to get it to play encores of “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” Then he tried to play the trumpet himself. The stars onstage paired off and began dancing — Cary Grant with Ingrid Bergman, Bob Hope with Zsa Zsa Gabor, Robert Wagner with Natalie Wood. At last, NBC spared the audience and the principals by cutting away to a short film.

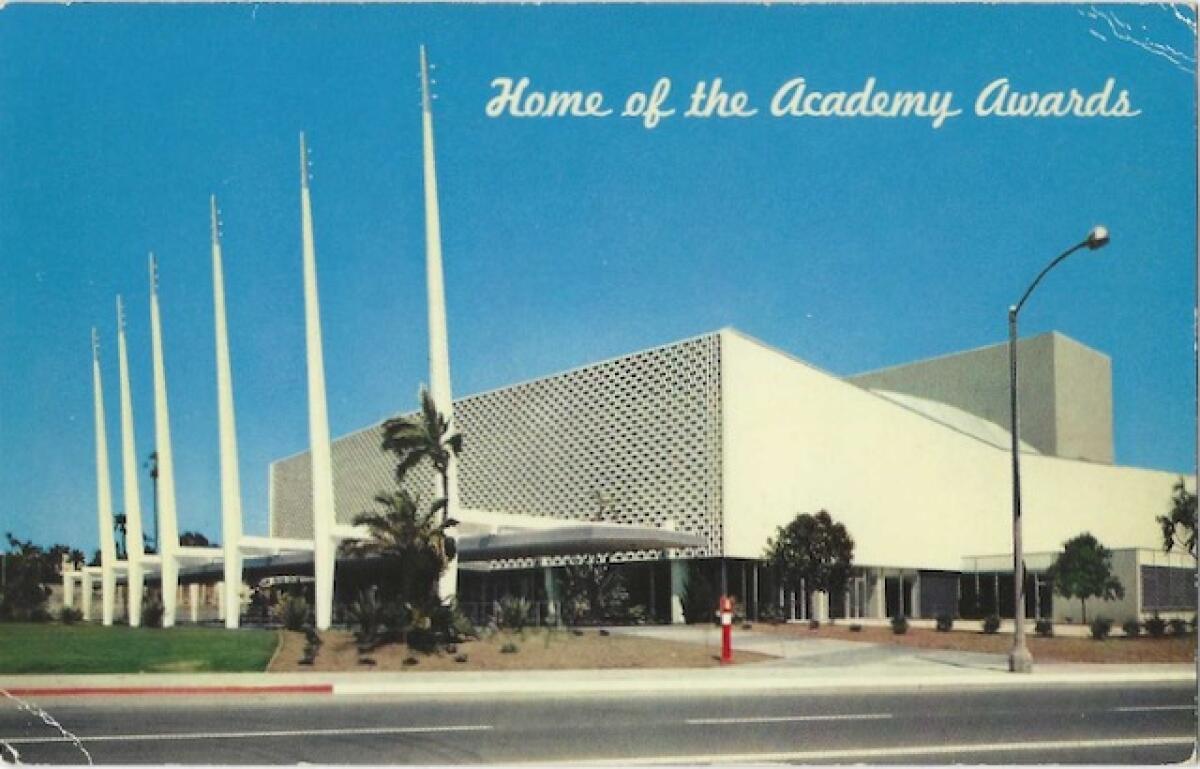

April 1961 A new decade, a new venue for most of the 1960s: the new Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. It was also a new show month: April. Here, in April 1968, the awards were postponed for two days because of the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. 1968 was also, according to theblacktieblog site, the last year presenters had to wear white tie and tails, although some of the men probably kept up the tradition. (In 1999, singer Celine Dion would show up on the red carpet in a white tuxedo — worn backward.)

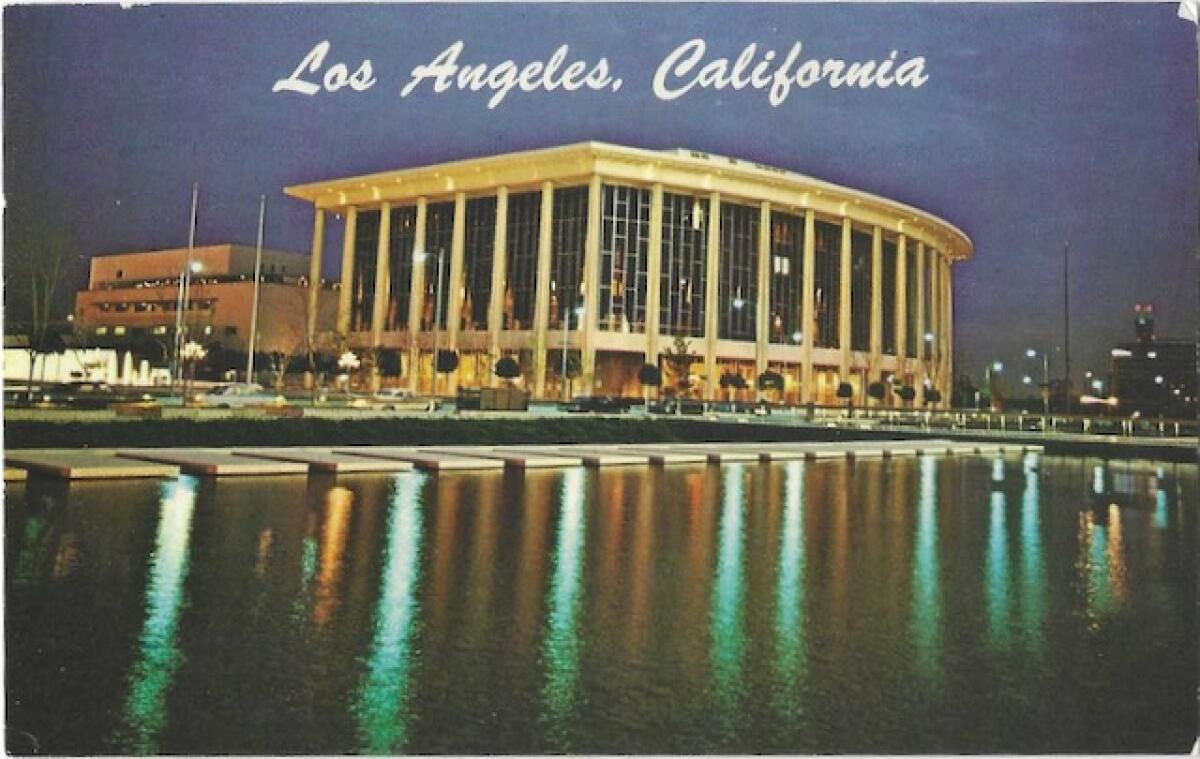

April 1969 At the cusp of the 1970s, the Oscars moved to downtown Los Angeles, to L.A. County’s spectacular Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, its home until 1988. This was the year that the academy gaveth and the academy tooketh away. A feature-length documentary, “Young Americans,” about a wholesome youth singing group touring the country by bus, won the Oscar. A few weeks later, its writer-director, Alex Grasshoff, heard from the academy: the film had been shown in a theater in October 1967, which made it ineligible for 1968 consideration. Grasshoff’s wife, Madilyn, said later that “it was a trial sneak preview in some little town in, like, North Carolina. I don’t know why they didn’t fight it, because it was not released.” [The academy has expelled three members over criminal convictions — Oscar-winning producer Harvey Weinstein, Oscar-winning director Roman Polanski and actor Bill Cosby — but has not reclaimed the Oscars. Cosby’s criminal conviction was later overturned by a court.]

April 1974 In the fad du jour, a man named Robert Opel snagged a press pass and streaked naked across the Oscars stage behind presenter David Niven, whose aplomb and lightning comeback —- about a man revealing his shortcomings — have to this day fed the debate about whether this was a planned or spontaneous streak. According to a New Yorker profile, Opel (original spelling Oppel) had been a speechwriter for Ronald Reagan’s gubernatorial campaign and later a curriculum consultant for the Los Angeles school district. He was shot to death in 1979 in a robbery of his San Francisco art gallery.

April 1978 Actress Vanessa Redgrave swung open the Oscar gates to personal politics. She had produced and narrated a documentary that was regarded in some quarters as supporting the Palestinian Liberation Organization. When she took the stage to take the best supporting actress Oscar, she also denounced “Zionist hoodlums whose behavior is an insult to the stature of Jews all over the world,” and pledged to “fight antisemitism and fascism for as long as I live.” Some in the audience booed, and outside, protesters burned her in effigy. There were rumors of police sharpshooters on the roof of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, ready to keep order.

March 1981 Postponed for only the third time — this time for 24 hours because President Ronald Reagan was shot the day the ceremony was originally scheduled. Host Johnny Carson said it would have been “inappropriate” to go ahead, because of the “uncertain outcome” of Reagan’s ordeal then. A day later, Reagan was doing well enough to ask for a TV in his hospital room to watch the awards. The academy played the one-minute remarks Reagan had taped two weeks earlier, lauding movies for showing that “people everywhere share common dreams and emotions.” Reagan called film “the world’s most enduring art form,” which must have puzzled admirers of Mozart, Giotto and the Lascaux Cave paintings.

April 1984 Some bold and divinely inspired producer booked Cheech and Chong to present a special visual effects Oscar for “Return of the Jedi.” The orchestra played them onstage with “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.”

March 1984 Prince won the Oscar for best original song score, and, flanked by the musical duo of Lisa and Wendy, walked onstage draped in a fabulous purple sequined hood of the sort that Marlene Dietrich might well have worn in the film “Morocco.”

April 1988 Back, after a long absence, at the Shrine Auditorium. The traffic was as miserable as the weather. Robert Osborne, in his magisterial history of the Oscars, wrote that the jams were so titanically awful that exasperated A-listers in all their gleaming finery ankled their limos and hoofed it down sweltering neighborhood streets to the auditorium. For several years thereafter, the awards ping-ponged between the Shrine and the Dorothy Chandler. Scheduling had become an obstacle, as it was explained years later in The Times. The L.A. Philharmonic and the L.A. Opera also used the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, and the increasingly elaborate Oscars production needed more and more rehearsal time.

March 2000 At the Shrine with the Oscars that almost couldn’t. Mailbags with about 80% of the Oscar ballots were misrouted, and ballots had to be re-sent. That was penny-ante compared to the news that a metal salvager had found 52 of that year’s Oscars statuettes, still plastic-wrapped, in the trash behind a Koreatown store. It’s a tangle of a tale. A shipping pallet with 55 Oscars disappeared from a trucking company loading dock in the city of Bell. The metal salvager, Willie Fulgear, who found 52 of them, got a reward, some felicitous publicity, a limo to the Oscars and an onstage shoutout from ceremony host Billy Crystal. Punishment was meted out to the thieves, who had presumably panicked at the publicity and dumped the “hot” Oscars — nothing short of pinching the crown Jewels would have conceivably attracted more attention. Also, the men who created “South Park” turned up on the red carpet dressed in their own fetching approximations of the daring green decollete and prom-dress-pink gowns that Jennifer Lopez and Gwyneth Paltrow wore to the Oscars the year before. Also, they dropped acid right beforehand.

March 2001 The last of the wandering awards ceremonies was at the Shrine. The next year, the event moved to the Hollywood & Highland theater that has borne the name first of Kodak and now of Dolby. The inaugural “forever home” Oscars, in March 2002, were the longest: 4 hours and 23 minutes.

February 2013 Only a few years before the hashtag #MeToo made activist Tarana Burke’s phrase into a call to arms against sexual abuse and harassment, Oscars host Seth MacFarlane performed a grotesquely cringe-worthy all-singing, all-dancing number “We Saw Your Boobs,” name-checking actresses like Meryl Streep and Kate Winslet, who had had brief topless film scenes; Streep’s was fast-flashing one breast in “Silkwood.” Leave that one on the ash heap of Oscar history.

February 2017 A distracted accountant hands the wrong envelope — a duplicate for the best actress award just given to “La La Land’s” Emma Stone — to Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, to award the last honor of the night: best picture. The only movie name Dunaway sees inside the envelope is the one she announced: “La La Land.” The exultant “La La Land” team swarms the stage, followed by gobsmacked academy staffers trying to sort things out. Then, a “La La Land” producer, Fred Berger, ends his thank-you speech with the words “We lost.” Beatty is given the correct card — for the best picture, “Moonlight” — and another “La La Land” producer, Jordan Horowitz, holds it up to show the name of the actual winning picture: “Moonlight.” That film’s director, Barry Jenkins, takes the stage, and Horowitz hands him the Oscar that, for a moment, he thought was his.

April 2021 The COVID split. Limited onstage presentations were made from the empty Dolby Theatre in Hollywood, observed by a rigorously tested and socially distanced audience of 170 stars and plus-ones at “pods” of tables and banquettes in downtown L.A.’s magnificent Union Station — a landmark that opened in 1939, the year you often hear referred to as the pinnacle of Hollywood moviemaking.

March 2022 The audience returns to the Dolby Theatre to see “He Who Gets Slapped” — not a remake of the 1924 silent film, but an apt description of Oscars host Chris Rock and the thwack heard and seen round the world. It was delivered to Rock’s chops by actor Will Smith, who shortly thereafter would take the stage again to win the best actor Oscar for “King Richard,” the driven and driving father of tennis stars Venus and Serena Williams, and to weepily apologize to the academy and to fellow nominees (but not to Rock). “Art imitates life,” Smith said. “I look like the crazy father.” He resigned from the academy not long thereafter.

March 2023 Top that, Oscars.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.