How the deluge of 1938 changed Los Angeles — and its river

Add another inch or two of rain in the late winter of 1938, and Angelenos would have been rounding up mountain lions and red-tailed hawks two by two, and shopping for enough gopherwood to float an ark.

Now here we are again, toweling off from what the news reports say is the worst storm in at least 40 years. Surely you’ve wondered, wow, what must those earlier “worst storms” have been like?

Wonder no more. Here’s the story of the epochal storms and floods of 1938.

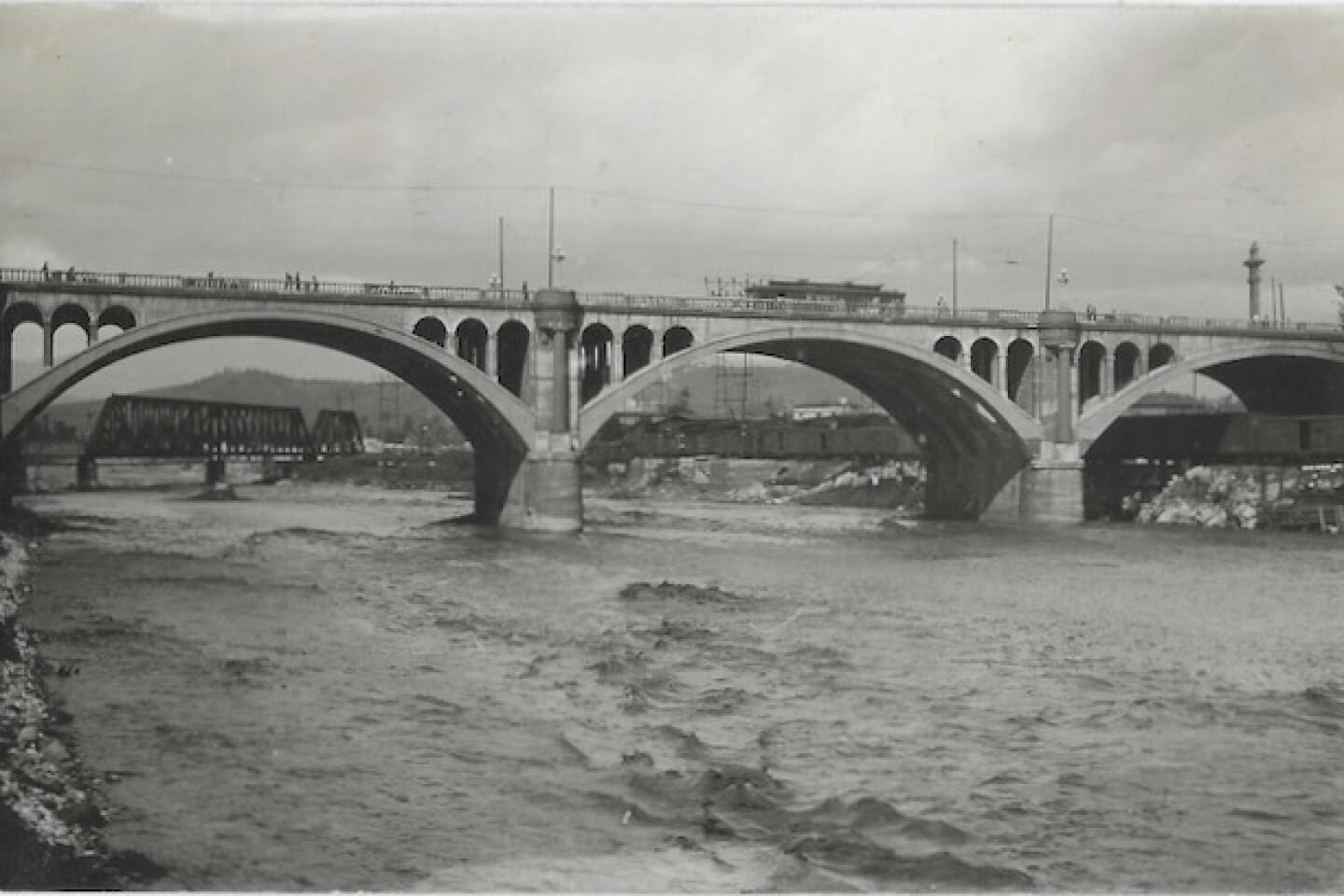

For five days, from the end of February into March 1938, a two-step weather combo of staggering force and volume crashed bridges, knotted railroad trestles, and crumbled highways and roads like soggy saltine crackers.

It turned Greater Los Angeles into an island unreachable save by radio — a medium that the supremely corrupt Mayor Frank Shaw, a spiritual brother to the truckling mayor in “Jaws,” used to deliver a PR spin that all this was no big deal, that “the sun is shining over Southern California today and ... Los Angeles is still smiling.” A week after the flood, Angelenos, already soured on Shaw’s crooked ways, started circulating the petitions that would bring about his recall.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Over those five days, at least a foot of rain descended across most of Southern California. Two and a half feet of rain beat down upon the face of the San Gabriels, wiping out the rustic resorts wedged into the canyons, and chuting runoff waters down onto the plain along ancient dry rivulets and freshets and canyons that Angelenos had forgotten or never known about. Where Santa Monica Boulevard crosses Vermont Avenue, the rain, as the weathermen reported dispassionately, “exceeded the computed maximum 50-year rainfall.”

Flood stories live in the warp and weft of legends and religions and nations — Gilgamesh, Noah, the Greeks and Aztecs, the Norse and Native Americans. Some of the 1938 flood accounts dwelled on our own pantheon: movie stars. Time magazine recited the inconvenienced celebrities: Lucille Ball’s wire-haired terrier turned up in her basement, swimming in 4 feet of water. Robert Taylor had to saddle up and ride two miles to get out of his flooded ranch near Chatsworth. Milton Berle’s car stalled over a manhole cover, which then blew with the force of a geyser and ruined his car. Franchot Tone’s car died and left him stuck, until he saw a bread truck and asked the driver for a lift. “Sure,” the man said, “but I’ll have to deliver this bread first.”

A look through criminal and gruesome appearances at Southern California lovers’ lanes may make you reconsider visiting one with your Valentine.

A huge prop whale, a plot point for a 1937 comedy called “Public Wedding,” came unmoored from the Warner Bros. prop yard and floated serenely down the Los Angeles River toward the sea. It was, as I wrote in my book “Rio LA, Tales From the Los Angeles River,” “a trompe l’oeil Moby Dick bound for the freedom of a real sea, not a cinematic one.” The Warners’ riverfront studio and actor Ralph Bellamy, whose house was yanked into the floodwaters, would end up suing the county flood control authority.

So many actors were marooned in their San Fernando Valley ranchlands that the Oscar ceremony was postponed for a week. Another delay wouldn’t happen again until 1968, after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and again in 1981, when a would-be assassin wounded President Reagan, a former actor who was to have helped open the Academy Awards.

As for the ordinary folk of L.A., there were tales of heroes and victims. A milkman named Ray J. Henville made his rounds by rowboat.

Henry Cooper, the caretaker for a rich man’s riverside estate, was lionized for playing a waterlogged Paul Revere, warning neighbors of the flood and six times ferrying stranded women (and his dog, Witchy) across the river to safety.

Pack horses ferried food up to the cabins of the artsy oddballs in Laurel Canyon. The canals of Venice for once resembled their Italian originals. L.A. County’s showman sheriff, Eugene W. Biscailuz, sent an air squadron over the foothills to drop parachutes of supplies to folks stuck in remote canyons. The Times tooted its own considerable horn about the armada of kayaks and rowboats it launched to deliver the newspapers.

When at last the waters were gone — and it must have felt like the 40 days and 40 nights of the Genesis flood — Los Angeles was a changed city.

The reckoning of the damages: about a billion dollars in current-day values for farmlands ravaged, bridges, roads and rail lines destroyed, and about 1,500 houses washed off the map. Bad as it was, it’s a fraction of what today’s equivalent damages would be, with the county’s population four times larger than it was then.

Over California’s history, floods have killed more people than earthquakes have, and in this flood, at least 96 people died, probably more. Five died when a bridge across the L.A. River at Universal City collapsed as they stood looking down at the waters. Perhaps ten more died when a wooden bridge over the same river in Long Beach splintered and broke up as they stood on it.

There was one more fatality: the natural Los Angeles River.

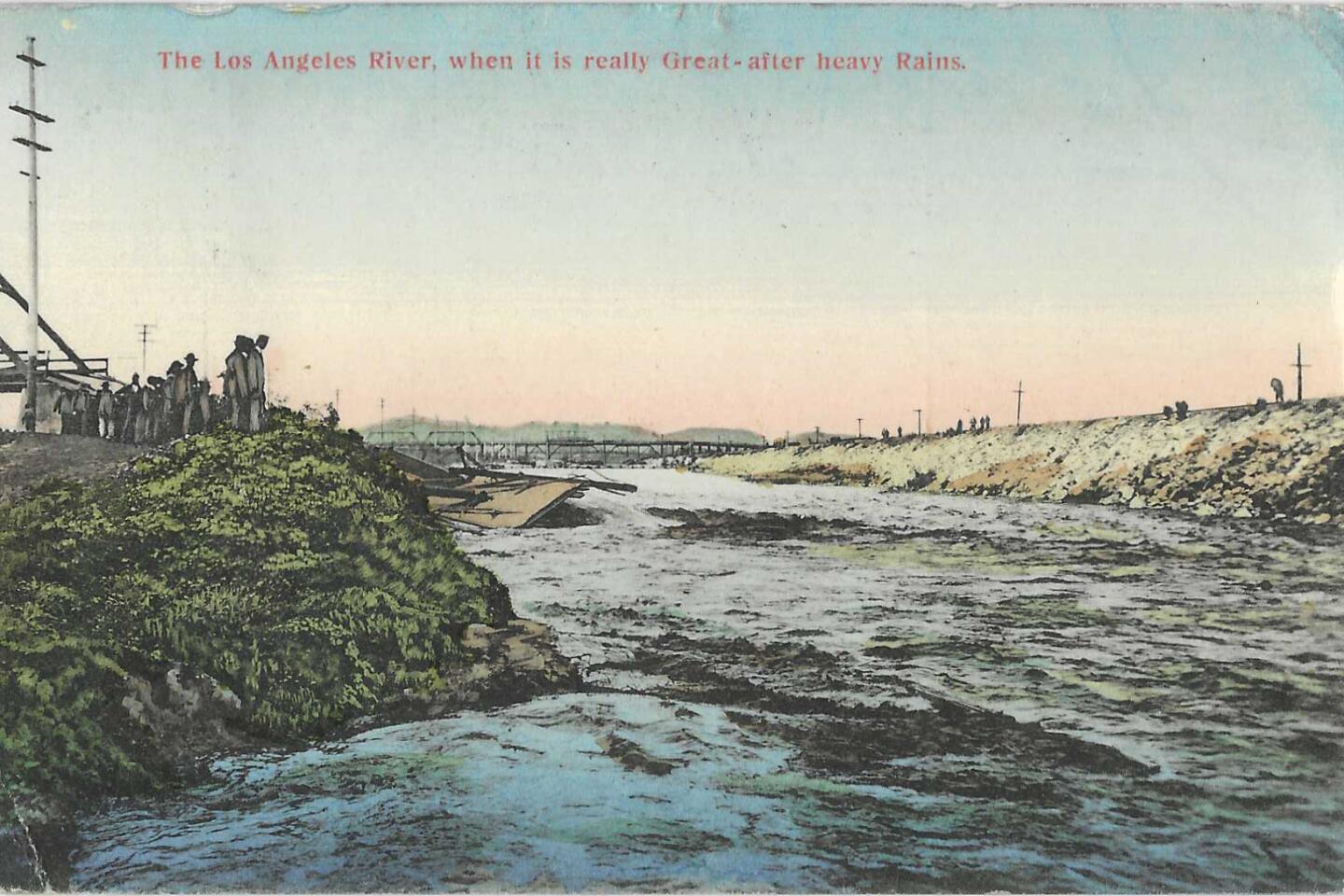

The river is the reason Los Angeles exists at all. Modern people think “L.A. = beach,” but it was along the river, with its fresh water and game and flora, where Native Americans settled and the Spanish and Mexicans and Yankees followed suit. The Tongva recognized two seasons of the river: “it is full of water” and “the water has departed.”

That river was a wandering, seasonal thing that played peekaboo, trickling through a braided network of little streams and existing springs. From today’s downtown, it coursed west and southwest all over the Los Angeles Basin until around 1825, when another flood redirected it toward where it flows today, more or less south from the original pueblo.

Sometimes, from its formidable mountainous watershed, the river flooded. The L.A. River and the Mississippi River both drop approximately the same distance — 800 and 600 feet, respectively — from top to bottom, but the Mississippi takes a leisurely 2,000-plus miles to descend. The L.A. River does it in a scant 50 miles, transforming it, in flood season, into a hurtling water chute.

Yankee L.A. was impatient with a river that didn’t pull its weight, unnavigable for goods or for people. In its capricious flows and floods, the river sometimes wandered far from anything like a deep-cut bed, and — its capital sin — chewed up valuable property and land.

After the river flooded in 1914, the county’s first flood control agency was organized. Then, the New Year’s Eve/New Year’s Day flood and mudslides of 1933/1934 killed scores — the totals were never agreed upon — in La Crescenta, Montrose, La Canada and Tujunga. That gave fresh urgency to building systems of dams, debris and catch basins, and other diversions. Some were in place in 1938, but not enough. Curiously, when Warner Bros. and actor Bellamy sued the county, it was because the already existing concrete river conduit “brought about an increase in the velocity of the river.”

The wild river, the one the newspapers called a “monster,” had to be controlled once and for all. After the Los Angeles Aqueduct opened the water taps a quarter-century before, the L.A. River looked like something worse than obsolete — it looked like a killer, of life, of land, of livelihood.

Thereafter, the great California historian Kevin Starr wrote, “at this point, the Army Corps of Engineers declared war on the Los Angeles River.” By 1939, it had planned river projects “approaching the cost of the Panama Canal.”

Thus, wrote Starr, did a public works project do its best “to destroy a river possessed of its own special sort of greatness, depriving Los Angeles in the process of its central landmark.”

The river paving neatly solved several problems. It meant thousands of jobs during the Depression. It meant preventing another 1938 catastrophe. On the flood plain of southeast Los Angeles County, where farms had once flourished, towns grew up, protected by the Pharaonic-scale concrete walls of the “built” river.

But the built river gave us another problem. Over centuries, the natural river had replenished Los Angeles’ groundwater. In 1939, as the straitjacketing of the L.A. River was well underway, Andrew R. Boone farsightedly wrote in Scientific American that “as much water as possible must be preserved to replenish ground water storage. The life of much of southern California depends upon such stored waters.”

Instead, this new, domesticated river was a high-speed water freeway, built to whisk away as much stormwater as it could as fast as possible.

And now, epochal drought is upon us, and sweeping away those trillions of gallons before our eyes seems profligate and a little bone-headed as Los Angeles pays to bring water from elsewhere.

As The Times noted a few weeks ago during early winter rains, “after so many months of drought-related water restrictions, it seemed to many like a missed opportunity” to grab back some of that fleeing water.

The Safe Clean Water Program passed by L.A. County voters five years ago apportioned more than a quarter-billion dollars a year to hold on to some of that stormwater and clean it up. Yet only a wimpy 30 new acres of green space have been set aside for this — “not moving the needle in a substantial way on both water quality standards attainment and water supply,” according to Mark Gold, who directs Water Scarcity Solutions for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The old river and its many tributaries with their ancient ways still underlie the modern chutes-and-ladders system for cushioning L.A. from its destructive pummelings; we have had a taste of that this month.

Three years after the 1938 flood, “City of Angels” was published. Its author was Rupert Hughes, a Hollywood polymath and uncle of Howard Hughes. As a Hollywood novel, it’s nowhere close to the greats like “The Day of the Locust.” But as a river novel, it’s splendid, and its principal villain is the 1938 flood.

Early in the book, Hughes writes of some out-of-town visitors who stop their car on a bridge over the wide and empty unpaved L.A. River. They are standing at the railing, pointing and laughing at the dry riverbed below them, when a motorcycle cop careens up to ticket them for stopping on a bridge.

He rebukes them for their ignorant mockery. “Stick around,” he says. “Till the rains begin. Then this old river will come down out of the mountains yonder and carry you and this bridge — and a dozen bridges with it — to hell and gone.”

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.