As a gang member, he killed a man. Now, he faces deportation to South Korea

After getting out of prison, Justin Chung told his story on podcasts and TikTok.

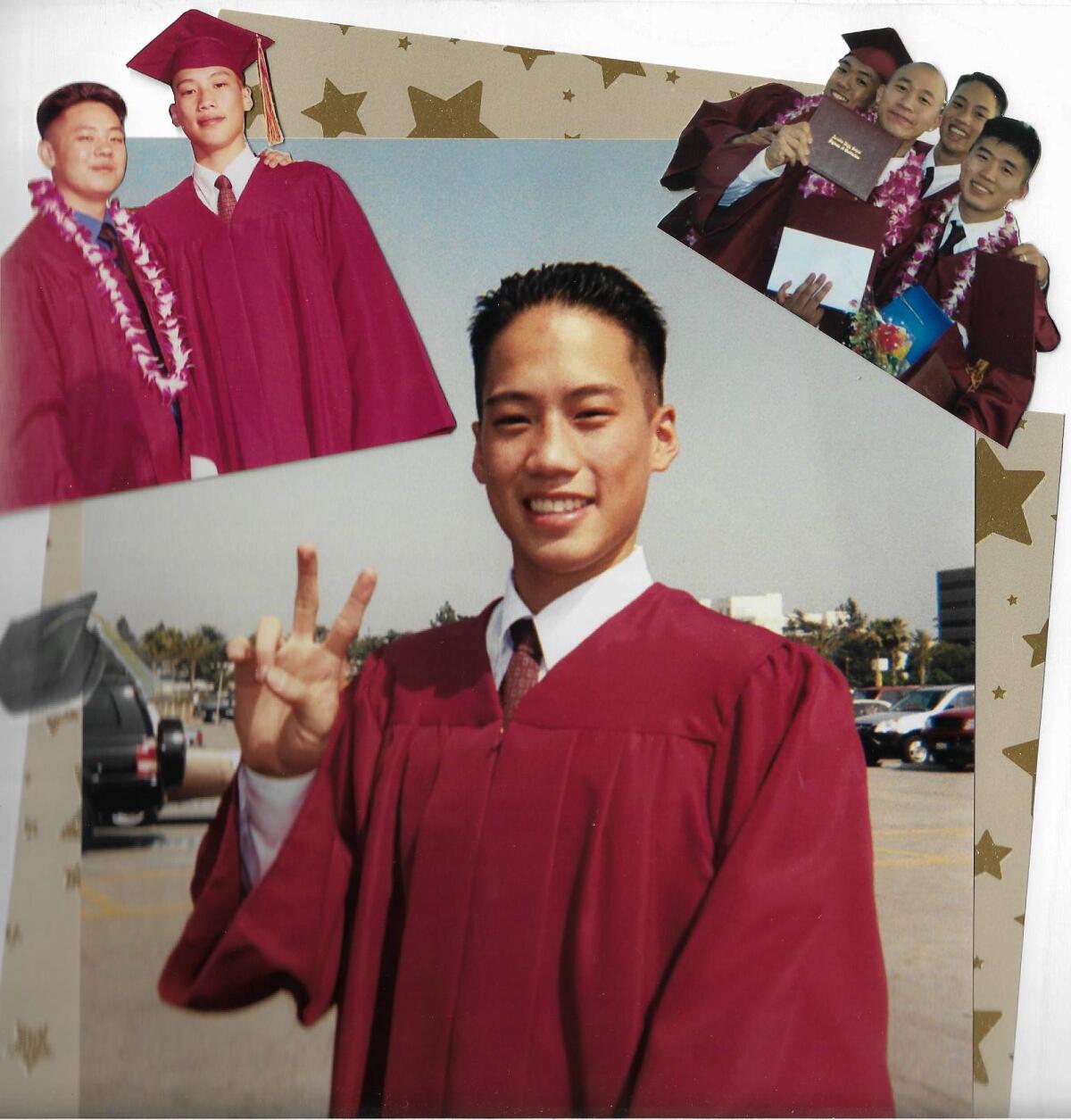

He knew he would face tough questions — that sharing about a graduation or family Thanksgiving would be punctuated by reminders of his horrible mistake.

“You took a life and the 14 years does not give the victim’s family any justice,” a TikTok user wrote.

Chung was brutally honest, admitting that it took him years to feel remorse. He wanted to share his complicated journey. And he was rallying support for another fight.

Because of the murder he committed when he was 16, he had lost his chance to apply for a green card. He is on the verge of being deported to South Korea, the country he left as a 2-year-old.

“Especially being Korean, I do want to be private, for my family,” said Chung, 33. “But I have to fight. I have to do something before I get deported.”

Like many Korean immigrants, Chung’s parents came to the U.S. more for him than themselves, hoping he would get good grades and stay out of trouble.

Chung remembers feeling lost. He fended for himself after school. His mother worked at a Korean video store, then a hamburger store, he said. She eventually started a clothing business in downtown L.A. with his father, a fashion designer.

As a high school student in Rancho Cucamonga, Chung was initiated into the Han Kook Boys, getting jumped and having his teeth knocked out. Amid the pain and fear, he felt a sense of belonging for the first time. They gave him a nickname — “Silent.”

The gang, whose name means Korean Boys, was small, about 15 members. As the maknae — youngest — Chung wanted to make a name for himself.

At a party in Rowland Heights on Aug. 17, 2006, an older Han Kook Boy confronted five young men, thinking they were members of a Chinese gang, the Wah Ching.

Chung had gotten into fights with Wah Ching members before. If his fellow Han Kook Boys had a problem with them, so did he.

“They were my hyung (brothers). They were my family,” he said recently.

As another Han Kook Boy, Pyung Hwa Ryoo, pulled a white Toyota Camry alongside the other group’s black Honda Accord, Chung rolled down the window on the front passenger side, aimed a Smith & Wesson .357 magnum and fired several times, according to court testimony.

Eric Sheng Huang, 21, died from a gunshot wound to the head. The driver, Calvin Yao, who was hit in the neck, chin and back, survived. Huang, Yao and the others in their car were not gang members, according to court documents.

Four months later, during history class, a voice on the intercom summoned Chung to the front office. Two detectives were waiting.

Chung was tried as an adult. In a Pomona courtroom on Oct. 17, 2007, a jury convicted him of first-degree murder with a street gang enhancement. He remembers his mother wailing. A fellow gang member’s father told him, “him-nae,” or “hang in there.”

A judge sentenced him to 82 years to life.

Co-defendant Ryoo was convicted of second-degree murder and other crime and sentenced to 15 years to life plus 50 years in state prison.

At Pelican Bay State Prison, Chung became a barber, able to cut hair for Latino, Black and white prisoners amid entrenched racial rivalries, since Asian Americans were “neutral.”

He got his GED and Bible college degree. He sat through countless hours of Criminal Gangs Anonymous. Some of it sank in. He learned how to identify his triggers for violence and how to avoid them, he said.

In 2018, then-Gov. Jerry Brown commuted his sentence to 15 years to life, citing his commitment to rehabilitating himself.

The next governor, Gavin Newsom, denied parole for Chung, but a judge reversed the decision, ordering Chung’s immediate release in June 2020, after nearly 14 years behind bars.

As is typical in murder cases involving non-U.S. citizens, Chung was sent to an immigration detention facility with a deportation order. But because of the COVID-19 pandemic, he was let go with an ankle monitor and an order to report regularly to immigration authorities.

Tin Nguyen, a refugee whose prison sentence had been commuted in 2018, was released from ICE detention in September

Chung was 30 and had never lived as an adult outside prison. He thought about learning how to code. But why not rely on a skill he had? Late last year, he graduated from a cosmetology program at Los Angeles Trade Technical College. He is a full-time hair stylist and financially supports his mother, who still works in the fashion industry.

Maybe in a different life, Chung and Huang could have been friends.

Huang, who went by Sheng instead of Eric, came to the U.S. from Taiwan when he was about 8.

At Arcadia High, he played violin in the orchestra and ran long-distance track, said a friend who asked that her name not be used because she fears retaliation from former Han Kook Boys. The gang is defunct, with some members deported to Korea.

For the record:

10:56 a.m. Feb. 19, 2023An earlier version of this story gave Eric Sheng Huang’s instant message handle as Asnquickie. It was AZNQuickie.

Huang’s instant message handle was AZNQuickie. He liked to play basketball and worked at a Tapioca Express boba shop.

He was a goofy boy who was always laughing, the friend said. He was also a caring person who would sneak out of his house at 11 p.m. to talk with a friend who was going through hard times.

The day before his death, Huang had taken a test to get his real estate license.

“I think about where Sheng would be now. He would probably be married with kids. His parents would have been grandparents,” she said. “They don’t get to have any of that, because Justin took that life for no reason.”

In a written statement, Huang’s family recalled hearing that a bullet had gone into his brain and that removing it would put him into vegetative state. His sister lost a young man she described as her “rock and support system.”

Fearing retaliation from the gang, the family sold their house.

In more than a hundred TikTok videos, ranging from funny and whimsical to serious and spiritual, Chung has been chronicling his life and the uncertainty he faces.

In one video, he cuts his mom’s hair and attends a family Christmas gathering for the first time in years, opening gifts and making gingerbread houses.

With sentimental piano music playing in the background, a TikTok slideshow begins with a photograph of a young Chung in a chambray prison shirt and jeans in a visiting room with his father.

“Destined for prison ... and to die in prison ... 14 years gone ... Grateful for another Thanksgiving ... With her ... “ the captions read, as shots of Chung’s girlfriend flash across the screen.

“And of course my momma,” the video concludes.

“He doesn’t give any criminal vibes,” another former prisoner says of Chung in a YouTube video where they discuss their prison experiences.

The occasional probing question or negative comment is a chance for Chung to respond with regrets and apologies.

“I’m truly remorseful. I am truly sorry for what I’ve done. I wish I can definitely go back and just take back what I’ve done,” Chung says on an episode of “Asian America: The Ken Fong Podcast.” “But I can’t.”

Chung’s Korean isn’t very good — just enough to get by, he said. Most of his family, including his mother and grandmother, is in the U.S. His father died in April 2016 while he was in prison.

Daily, when they say goodbye to family and friends, many Cambodians fear it will be the last time they see them. Supporters are pushing for due notice for immigrants threatened with ICE deportation, after judge’s ruling.

Immigrant rights advocates and others, including Irvine Vice Mayor Tammy Kim, have rallied to Chung’s cause.

“What I saw with Justin — could have been my brother,” said Kim, who was an infant when she left Korea.

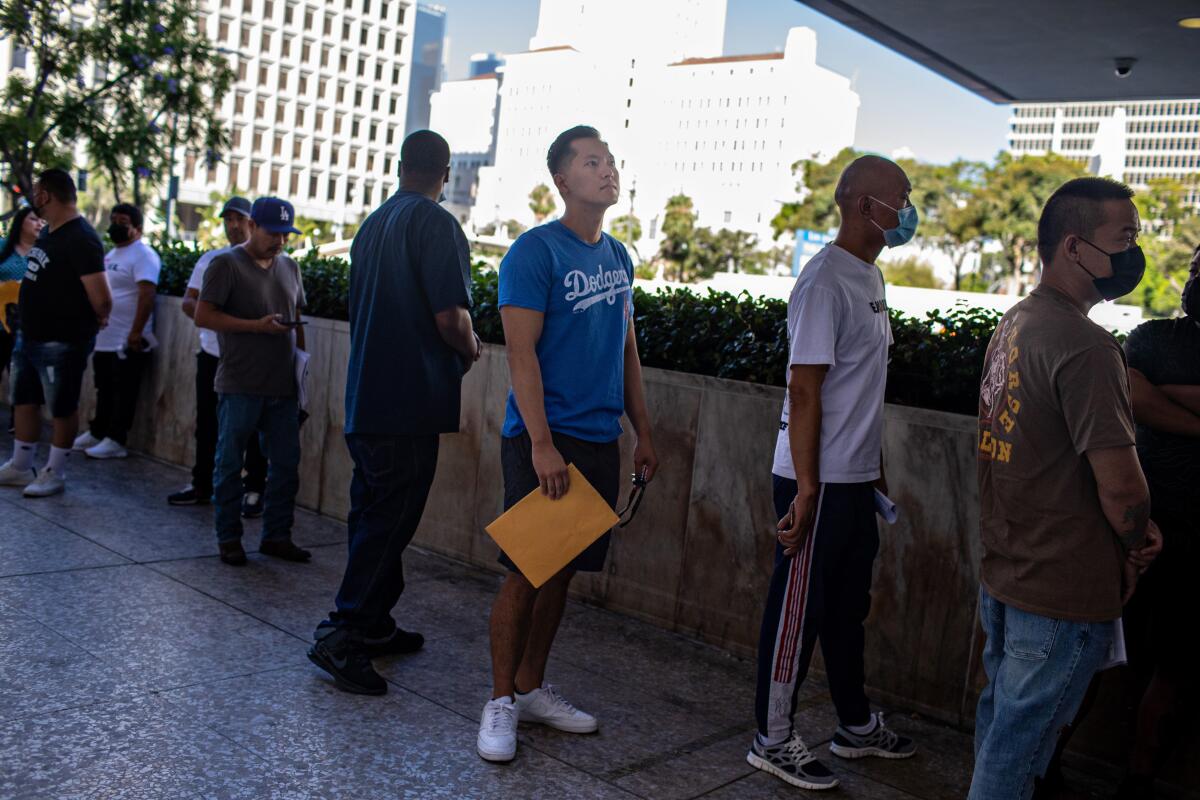

In a blue Dodgers T-shirt, shorts and white sneakers, clutching an envelope containing his paperwork, Chung blended in with the other immigrants waiting for appointments at a federal building in downtown Los Angeles one day last summer.

Since his release from prison, he has checked in with immigration officials a dozen times. At every meeting, his deportation could begin. He is scheduled to report there again Tuesday.

He is hoping for a pardon from Newsom, which could make a judge more inclined to reverse his deportation order.

Chung worries that telling his story could traumatize Huang’s family and friends.

But he wants to humanize his situation for the Asian American community, where those returning from prison can be stigmatized. And for him, the more support he has in fighting his deportation, the better.

He has raised the idea of meeting Huang’s family. But by law, they need to initiate the contact.

To hear Chung talk about the shooting as “gang related,” Huang’s family said, is very hurtful. The family said that for Chung to suffer deportation would be “nothing” compared with what they have been through.

“Every action Justin takes is making our family relive the pain of him taking Sheng away from us,” the family said.

To Huang’s friend, starting over in a strange land is a just consequence for taking a life.

She recalls holding Huang’s hands moments before doctors pulled the plug on Aug. 19, 2006. She didn’t attend Chung’s trial — it was too painful.

“If you are really sorry, just go to Korea,” she said. “It’s part of what God has given you.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.